DISCLAIMER

The draft recommendations contained herein were preliminary drafts submitted for discussion purposes only and do not constitute final determinations. They have been subject to modification, substitution, or rejection and may not reflect the adopted positions of IFATCA. For the most current version of all official policies, including the identification of any documents that have been superseded or amended, please refer to the IFATCA Technical and Professional Manual (TPM).

61ST ANNUAL CONFERENCE, 23-27 May 2022WP No. 67Autoland Communication Between Pilots and Controllers in Good Weather ConditionsPresented by TOC |

Summary

Autoland is a procedure performed by pilots all over the world and its use is expected to become more common in the future. There are no international standards that require pilots to notify controllers when they are performing an autoland. A questionnaire performed by IFATCA about autoland communication shows that both controllers and pilots have different expectations about what each will do during an autoland. IFATCA currently has no policy on autoland but an incident that occurred in 2011 demonstrated the safety implications of this issue.

Introduction

1.1 On November 3, 2011 a serious incident occurred at Munich involving a B777-300ER that suffered a lateral runway excursion while conducting an autoland in CAT I conditions. Luckily no persons were hurt, nor was the aircraft damaged. The German Federal Bureau of Aircraft Accident Investigation (BFU) report on the incident was published in December 2018.

1.2 The Assessment section (2.6) of the report contains the following text, here translated into English: “The investigation has shown that automatic landings are carried out under CAT I conditions without informing air traffic control. If, in such cases, there were international rules to inform ATC of the imminent automatic landing, the air traffic controllers would have been better prepared and would have possibly taken the necessary precautions. To inform ATC in advance of an imminent automatic landing if the airport does not operate under LVP should become a global standard.”

1.3 There are no provisions in ICAO documents on the need of autoland intentions being communicated to ATCOs.

Discussion

2.1 Autoland describes a system that fully automates the landing phase of an aircraft’s flight, with the human crew supervising the process. The aircraft uses signals from ILS (or it may use MLS or GLS when these are installed and approved for use) as well as radio altimeters to drive actions by autopilot, auto-thrust and nosewheel steering. The pilots assume a monitoring role during the final stages of the approach and will only intervene in the event of a system failure or emergency.

2.2 Autoland is designed for use in meteorological conditions that are too poor to permit a visual landing but depending on aircraft type and the autopilot system installed, autoland may be used in any weather conditions at or above the published minima on any runway.

2.3 Strict low visibility procedures (LVP) require tower controllers to protect the ILS critical and sensitive areas in conditions below CAT I minima to ensure the quality of the ILS signals received by aircraft. The initiation of LVP may also include reduced switchover times of ground-based navigation aids in the event of a failure. When autoland is conducted in weather conditions above the CAT I minima, the protection of these areas is not guaranteed, and the switchover times of ground-based navigation aids may increase. This increases the risk of erroneous ILS signals being received by aircraft with the potential for an autolanding aircraft to veer off course during a critical phase of flight, necessitating quick overriding action by pilots to correct the deviation or go around.

2.4 Operators define the criteria for pilots to conduct an autoland both above and below CAT I minima. Operators may require their pilots to practice autoland in good weather in order to maintain crew competency and to demonstrate the ongoing functionality of the aircraft systems.

2.5 The ICAO Flight Operations Panel discussed the topic of autoland announcements to ATC in their sixth meeting which was held in October 2019. The panel report says while the topic is valid, it is complicated by the differences between ILS and other landing systems as well as differences in local conditions; therefore, an adapted solution may be required. It was also noted that a difference exists between performing an autoland for pilot training, for which no notification to ATC is required (as pilots could react to signal disturbances) and those where pilots rely on signal protection even if weather conditions do not make this evident to ATC. A proposed amendment to the ICAO All Weather Operations Manual discusses the conduct of autoland including pilot actions and safety considerations.

2.6 Autoland is performed at numerous airports in various countries. A review of some available AIPs has provided several methods employed by ANSPs to manage the conduct of autoland and a selection of these are detailed below.

2.6.1 Australia

In weather conditions where the ceiling and/or visibility are above CAT I minima, the pilot shall inform ATC about any intention to conduct:

a) an approach with minima less than standard CAT I; or

b) an autoland procedure.

This information must not be taken as a request for or expectation of the protection of the ILS but to enable ATC to inform the flight crew of any known or anticipated disturbance (AIP Australia, May 2019, AD 1.1, p. AD 1.1-2).

2.6.2 France

They [pilots] must point out, when first making contact with air traffic control, that they intend to make a CAT III precision approach for training or an automatic landing. This in actual fact determines the setting up of specific separation between aircraft, whose purpose is to ensure that the ILS signal is functioning correctly. If this cannot be applied or if certain particular circumstances make it necessary, clearance will not be given, or the procedure could be interrupted by air traffic control services (AIP France, Jan 2019, AD 1.1.3 and AD 1.1.3.4, p. AD 1.1-5).

2.6.3 Spain

Pilots who wish to carry out training for CAT II and III approach must request categories II and III approach on initial contact with approach control. For practice approaches there is no guarantee that full safeguarding procedures will be applied, and pilots should foresee the possibility of the resultant ILS signal disturbances (AIP Spain, May 2018, AD1.1, p. AD 1.1-5)

2.6.4 USA

If an aircraft advises the tower that an “AUTOLAND” “COUPLED” approach will be conducted, an advisory will be promptly issued if a vehicle/aircraft will be in or over a critical area when the arriving aircraft is inside the ILS middle marker. Example: CRITICAL AREA NOT PROTECTED. No authorization for vehicles or aircraft to transit critical areas (except for aircraft that land, exit a runway, depart, or execute a missed approach) if aircraft are in regions that could be affected. The exception is not applicable if ceiling is below 200 ft or RVR less than 2000 ft. If ceiling is below 200 ft or RVR is less than 2000 ft, do not authorize vehicles or aircraft operations in or over the [critical] area when an arriving aircraft is inside the middle marker, or in the absence of a middle marker, 1⁄2 mile final” (AIP USA, Jan 2020, ENR4, p. ENR 4.1-10).

2.7 The review above shows that regulations and procedures for autoland differ per country. Apart from that, it is implied that the expectations associated with autoland procedures vary among both pilots and ATCOs. In order to validate this, research was performed by IFATCA TOC in October 2019.

2.8 IFATCA distributed two questionnaires: one to ATCOs and another to pilots (with the assistance of IFALPA). Similar questions were asked of both groups in order to compare the answers. Forty-five answers from ATCOs and 129 answers from pilots were received.

2.8.1 The Q1 for ATCOs was “Do you recognize that pilots perform autoland when not LVP?” and the result shows about 55% ATCOs did not recognise it. On the other hand, the Q1 for pilots was “Do you report to ATC that an autoland will be performed in good weather conditions?” and the results were that more than 60% of them report their intention.

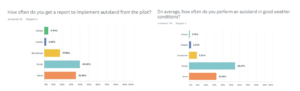

2.8.2 The Q2 for ATCOs was “How often do you get a report to implement autoland from pilots?” and the result shows it’s not many times. The Q2 for pilots was “On average, how often do you perform an Autoland in good weather conditions?” and the result shows it’s rare and about 30% have not performed it.

2.8.3 The Q3 for ATCOs was “Are there company regulations regarding autoland in your workplace?” and the result shows about 80% have no rules. The Q3 for pilots was “Are there company regulations regarding autoland in good weather conditions?” and the result shows more than half of companies have rules.

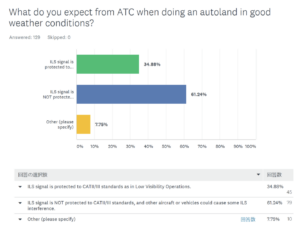

2.8.4 The Q4 for pilots was “What do you expect from ATC when doing an autoland in good weather conditions?” and the result show various expectations which differ between countries and airlines. Under the option “other”, the answers mainly confirmed the need for information to pilots on the protection given when performing an autoland.

2.8.5 The Q5 for ATCOs was “Do you have any reports of accidents, minor incidents or communication errors related to autoland?”. The result shows most countries have no accident reports related to autoland. The Q5 for pilots was “Do you have any reports of accidents, minor incidents or communication errors related to autoland in good weather conditions?” and the result shows there were a few reports. Most of the comments referred to the incident in Munich and one comment reported localiser fluctuation on very short final.

2.8.6 The Q6 for ATCOs was “Do you think any standards or any rules are needed between pilots and air traffic controllers regarding autoland?”. About 70% of MAs think there is a need for standardising the autoland operation. The Q6 for pilots was “Do you think any standards or any rules are needed between pilots and air traffic controllers regarding autoland in good weather conditions?” and the result shows about 60% think there should be standards.

2.9 The Q1 to Q6 for ATCOs shows that about half of ATCOs have no recognition of pilots performing autoland when LVP are not in force because it is rarely occurring in their daily operation. About 80% of countries have no rules or regulations in their local operations manual or AIP. But about 75% of ATCOs recognised the need for a standardised approach to aircraft performing autoland when LVP are not in force.

2.10 The Q1 to Q6 for pilots shows that more than half of pilots perform autoland and report to ATC, but their expectations are different. About 60% of operators have their own rules or regulations for autoland. About 60% of pilots recognized the need for a standardised approach to aircraft performing autoland in good weather conditions.

2.11 The results of the questionnaires show that the pilot and controller understanding of autoland procedures are not always aligned. It is not clear whether these differences are sufficiently known in the pilot community and whether (and where) guidance for pilots exists. On the other hand, it is clear that both the increasing prevalence of landing systems supporting autoland, and aircraft capable of performing autoland, will see an increase in the frequency of its use.

2.12 A misaligned understanding of pilots and controllers has the potential to cause incidents with significant safety implications. For example, when ACAS was introduced in the past, incidents occurred where the understanding of the controller and pilot were not aligned, and this misalignment contributed to adverse outcomes. The official investigation by the German BFU identified ambiguities in ACAS procedures as the one of main causes of the Überlingen mid-air collision. Seventeen months before the accident, there had already been another occurrence of confusion between conflicting ACAS and ATC commands: in 2001, two Japanese airliners nearly collided with each other in Japanese airspace when one of the aircraft received conflicting orders from ACAS and ATC, and one pilot followed the instructions of ACAS while the other did not.

2.13 The ambiguities that existed in ACAS procedures, which contributed to such serious occurrences, should serve as a reminder of the dangers of misaligned understanding between controllers and pilots. For example, a pilot may inform the tower controller that they are conducting an autoland, to which the controller acknowledges by saying “roger”. The pilot might assume that the acknowledgement means the ILS critical and sensitive areas are protected, while the controller might assume that there is no need to protect these areas nor inform the pilot since the pilot should be aware that LVP are not in force.

2.14 To prevent such a situation, controller and pilot understanding of autoland procedures should be aligned. Standard phraseology and local procedures on whether or not an autoland is approved, and whether or not the critical/sensitive areas are protected, should minimise possible ambiguities and prevent undesirable outcomes such as what occurred in 2011.

Conclusions

3.1 Autoland operations in good weather conditions are conducted regularly all over the world. Due to the continuing implementation of landing systems and aircraft systems that support autoland, it is expected to occur even more frequently in the future.

3.2 ICAO has no global standards on autoland communication, and a questionnaire of both pilots and controllers has indicated that they do not always share the same understanding of autoland procedures.

3.3 Previous incidents have demonstrated the dangers of ambiguous procedures and misaligned understanding between pilots and controllers. Developing standard phraseology and procedures should eliminate such ambiguities and prevent further undesirable outcomes associated with the conduct of autoland in good weather conditions.

Recommendations

4.1 It is recommended that IFATCA policy is:

Local procedures should be developed for performing an autoland or practice CAT II/III approaches when Low Visibility Procedures are not in use.

If such procedures are not defined, and the pilot indicates the intention to perform an autoland or a practice CAT II/III approach, ATC should notify the pilot if the ILS sensitive areas are not protected.

Standard phraseology should be developed for such a notification

And is included in the IFATCA Technical and Professional Manual.

References

ICAO Flight Operations Panel meeting report, sixth meeting, October 2019.

Investigation report, AX001-1-2/02 May 2004, German Federal Bureau of Aircraft Accidents Investigation.

Investigation report, BFU EX010-11 November 2011, German Federal Bureau of Aircraft Accidents Investigation.

AIP Australia, Nov 2019, Airservices Australia.

AIP France, 30 Jan 2020, French General Directorate of Civil Aviation by the Aeronautical Information Services.

AIP Spain, 30 Jan 2020, The Aeronautical Information Service of Direccion de navegacion aerea.

AIP United States of America, 25th edition, September 2018, amendment 3, department of Transportation Federal Aviation Administration.