54TH ANNUAL CONFERENCE, Sofia, Bulgaria, 20-24 April 2015WP No. 93Crisis ManagementPresented by PLC and TOC |

Summary

Crisis management is an important present-day issue, with many global and regional initiatives to help the aviation industry cope with major disruptions. To effectively manage a crisis situation, an up-to-date crisis and contingency plan is an important first step.

This paper provides general guidelines on the different phases in handling crisis situations and stresses the importance of the availability of an up-to-date crisis management planning. Furthermore, this paper encourages going beyond the local policy by communicating across the border and consulting experts.

Introduction

1.1. Small and large crisis situations affect ATS (Air Traffic Service) units. Whether it’s directly aviation related, a political disturbance or a natural disaster: each crisis leads to instability in Air Traffic Control (ATC) that may impact both the system and personnel.

1.2. In recent years there have been many crises affecting aviation considerably. A few examples are the Haiti earthquake, air travel disruption due to volcanic ash, the Libya situation and most recent the Ukraine crisis. However, a crisis can also be a local affair, for example an OPS-room evacuation. Although the impact and duration may differ, the approach is still the same.

1.3. It seems common that in the first period that follows any crisis situation, disorder prevails. Contributing factors can be lack of information sharing, a difficult balance between states, contingency plans being out of date, ambiguous or not yet in operation or traffic overload.

1.4. The effects of a disorder are likely to significantly affect adjacent airspaces as well. International coordination on contingency plans and repression measures is desirable to optimize solutions and to ensure that Air Traffic Services continue to operate.

1.5. IFATCA produced the Crisis Response and Communications Planning Guide (Tanzania, 2008) to help MA’s dealing with events, which could be categorized as a crisis. This guide calls for ANSP’s to have contingency plans, which are regularly trained and updated, in operation.

1.6. This paper aims to give a broader view on crisis management, by at first defining the terms and categorising crises, then offering a theoretical framework and finally providing guidelines for MA’s that are implementing or improving crisis management.

Discussion

2.1. International developments

2.1.1. At the IFATCA conference in Arusha, Tanzania in 2008, the IFATCA Executive Board presented the Crisis Response and Communications Planning Guide as a guideline for the Member Associations to help in the process of preparing for, and dealing with events which could be categorized as a crisis, or which could evolve into a crisis.

The Planning Guide describes seven steps to prepare and prevent crisis situations:

- First step: higher values and considerations, general interest and main tasks. The aim is to define a solid basis and a framework to establish a portfolio.

- Second step: identify the risk and situation, which could lead to a crisis. The aim is to identify potential crisis situations.

- Third step: formal risk assessment with the aim to gather crisis situation or different crisis types into a grouping.

- Fourth step: the grouping will now be associated to real potential damaging risks which could lead to crisis assessed and grouped in a crisis portfolio.

- Fifth step: how do you prepare yourself to cope with the chosen crisis portfolio? How far is your crisis preparedness?

- Sixth step: where are we compared with where we should be with the readiness of our preparedness.

- Seventh step: develop crisis scenarios and add new and future potential ideas into this thinking.

The IFATCA Crisis Response and Communications Planning Guide can be seen as a first important practical step IFATCA took in helping MA’s with crisis management. However, recent crises in aviation showed that there is a need for joint principles in the theoretical approach to crisis management, prior to the more practical steps of the IFATCA guide. The crisis guide could be improved by inserting information the aviation community has learned from recent crises and other disruptions in ATS, and providing more information on the theoretical approach to crisis management.

2.1.2. The European Commission and Eurocontrol established the European Aviation Crisis Coordination Cell (EACCC) in May 2010. In imitation of the major disruption of the aviation network after the eruption of the Icelandic volcano Eyjafjallafökull, the main role of the EACCC is to support coordination of the response to network crises impacting adversely on aviation, in close cooperation with corresponding structures in States. Its role includes proposing measures and taking initiative to coordinate the response to crisis situations, and in particular acquiring and sharing information with the aviation community in a timely manner. EACCC also aims to link national contingency plans with those established at network level. Furthermore EACCC organises crisis management exercises to test how States, aircraft operators and other stakeholders would respond and coordinate during a crisis situation. The EACCC was joined by EASA very soon after its establishment.

2.1.3. In the event of a crisis, the EACCC gathers and contacts State Focal Points (individual who will act as an intermediary between NM/EACCC and his/her state), to jointly discuss, agree and approve a crisis-mitigation policy. The State Focal Points make sure that this policy is in accordance with national procedures and coordinate the response. The EACCC also gathers, prepares and shares all relevant information with the entire aviation community.

2.1.4. Alongside, the Eurocontrol Network Manager published a network disruptions management procedure (2011). This procedure was developed to manage disruptions and crises impacting aviation in Europe.

2.1.5. In 2011 the ICAO Risk Context Statement (RCS) was established to develop a risk assessment methodology. This statement also provides a high-level description of the current global risk picture based on intelligence and information sharing. Furthermore it assists ICAO in improving SARPs and guidance material. The RCS does not attempt to create a detailed view of national or local risks.

2.1.6. The subject of regional crisis management and coordination was discussed on the Twelfth Air Navigation Conference (ANC12), held in November 2012 in Montréal. Eurocontrol, the European Union member states and other European Civil Aviation Conference (ECAC) member states presented a paper about the actions taken after the 2010 volcanic ash event, including the foundation of the European Aviation Crisis Coordination Cell (EACCC). The paper recommended that the ICAO regions should consider how crisis coordination arrangements similar to the European could be established on a regional basis and that the ICAO regions publish, maintain and exercise practical contingency plans for potential disruptive events, including those events that may adversely impact aviation safety.

2.1.7. In imitation of the paper presented at the ANC12, the European region took the initiative within the European Air Navigation Planning Group (EANPG) to establish a standardised crisis management framework based on a common concept for the management of crisis situations, regardless of the type of crisis. The EANPG is currently working on this framework, which will, for example, include crisis coordination arrangements and crisis management principles.

2.1.7.1. The crisis management framework should propose guidance to States, assisting them with enhancing the level of preparedness to threat scenarios. Experiences and arrangements from the EACCC will be used and the framework should be in line with global ICAO provisions. It can be used as a basis for pan/intra-regional cooperation and aims to harmonise the crisis management approach across the whole European Region.

2.1.7.2. In the draft, among other things, the following recommendations will be made:

- Develop an informal national network for consultation on potential next major disruption/crisis.

- In addition to partnerships established at the national level, consideration should be given to building partnerships at the regional level (…).

- As crisis often spills over the boundaries of States or Regions, in addition to partnerships established at the national and regional level, it is essential to establish close cooperation with key stakeholders beyond the boundaries of the Region, in this particular case beyond ICAO EUR Region.

2.1.8. In addition to the EANPG initiative, ICAO established an Emergency and Incident Response (EIR) process to coordinate the flow of information between ICAO headquarters and other interested parties within the aviation industry.

2.1.9. The downing of the Malaysian Airlines flight in July 2014 ICAO, among others, caused the establishment of a senior-level Task Force to address issues related to the safety and security of civil aircraft operating in airspace affected by conflict. The Task Force on Risks to Civil Aviation arising from Conflict Zones (TF RCZ), in which IFATCA is also involved, came to the view that there is significant room for improvement to reinforce and enhance the operation of the civil aviation system to cope with risks in conflict zones.

The main objectives of this Task Force are to ensure that:

- robust arrangements are in place to identify, assess, share information on and respond to risks to civil aircraft from activities in conflict zones; and that

- these arrangements apply, and relevant information is available, to assure the safety of passengers and crew on civil aircraft, irrespective of which airline they are travelling with or which cities they are travelling between.

2.2. Definition

2.2.1. Many Air Navigation Service Providers (ANSPs) have crisis- and contingency plans in operation. However, the basic principles that underlie these plans are different. It is not always clear when an event should be called a crisis and thus the regulations should be in force.

2.2.1.1. Not all (major) disruptions have to be a crisis situation. Disruptions in the Air Traffic Management (ATM) or Air Traffic Flow and Capacity Management (ATFCM) system are regular and often occur on a daily basis. They are handled with existing procedures and manageable within the Operations (OPS) framework. This includes most emergencies and degraded system situations.

2.2.1.2. A crisis can emerge from an unpredictable event / disruption, or as a consequence of an event that had been considered a potential risk. Crisis situations can have major, even global impact and can have political and media implications. In either case, crises almost invariably require that decisions be made quickly to limit damage to the organization. Crisis- and contingency plans are the first step to manage a crisis effectively, but it is almost inevitable to go beyond what is required. They and have a need for a network crisis cell, which will gather information, decide a course of action and manage the crisis response.

2.2.1.3. According to the IFATCA Crisis Guide:

A crisis is any event or situation that could:

- hinder the ability of an air traffic control unit to operate effectively, or

- damage the reputation of an air traffic control unit (or Service Provider) with stakeholders, users, and the public, all of whose support is essential for successful operations.

However, a situation that hinders the ability of an ATC Unit to operate effectively doesn’t necessarily have to be a crisis situation. For example: in cases of bad weather, an air traffic control unit is also hindered to operate effectively while this can be a completely manageable situation. A second example: damage to the reputation of an ANSP doesn’t always influence the ability to provide air traffic control at the required level. This damage might be caused due to management decision or retrenchment and resignations, which have nothing to do with ATS operations.

2.2.1.4. Although no ICAO crisis definition can be found in the ICAO documents, Eurocontrol and the ICAO European Air Navigation Planning Group (EANPG) use the following:

“Crisis: state of inability to provide air navigation service at required level resulting in a major loss of capacity, or a major imbalance between capacity and demand, or a major failure in the information flow following an unusual and unforeseen situation”

A state of inability causing a major loss of capacity, imbalance between capacity and demand, or failure in the information flow should certainly be considered a crisis. However, a crisis situation is not limited to these results. As stated before, not every accident is a crisis, yet some accidents can certainly be determined as a crisis situation. Furthermore, a crisis doesn’t necessarily have to be an unforeseen situation, since it can evolve and thus be predictable.

A runway crash will cause a major loss of capacity and therefore is a crisis situation. But according to the definition above, the Überlingen accident could not be called a crisis: there was no capacity loss, no direct imbalance and no failure in the information flow following the crash. The Überlingen case is an example of the fact that the term ‘crisis’ should be more broadly defined.

2.2.1.5. It is therefore proposed that the IFATCA definition is:

“Crisis: state of inability to provide air navigation service at required level, affecting system and/or personnel, following an unusual or unforeseen situation.”

2.2.1.6. For crises in ATM, a distinction should be made between:

- Events that have an internal cause (e.g. system failure) or external (e.g. natural disaster);

- Crises that we cannot predict and/or control (e.g. earthquake) and crises that can be more or less predicted and/or managed (political, economic, etc.);

- A big impact on ATS (e.g. volcanic ash, airspace closure) or a smaller, linked impact (e.g. small traffic increase due to a situation in a neighbouring state);

- Short-lived (e.g. quickly resolved evacuation) and extended (e.g. conflict between states). This is directly related to the time that is needed to recover from the crisis.

These distinctions are visualized in the following illustration:

ATM Crisis Distinction (R. Pauptit & S. Verpalen, 2014)

2.2.2. The way a crisis is dealt with is called crisis management. According to the Oxford dictionary the basic definition is as follows;

“Crisis Management; the process by which a business or other organization deals with a sudden emergency situation.”

Crisis management involves identifying a crisis, planning a response and confronting and resolving the crisis. It could be considered effective when operations are sustained or normal operations are resume. Furthermore learning should occur so that lessons are transferred to future incidents.

2.2.3. Part of a successful crisis management is a proper contingency planning, the process of preparing for a potential crisis. According to the Oxford dictionary:

“Contingency plan; a plan designed to take account of a possible future event or circumstance”

Contingency planning involves setting the policies and procedures, which will guide an organisation in case of overlooked, possible emergencies. This can include documentation of guidelines but also activities such as a simulated exercise in order to be better prepared or to identify weaknesses crisis management procedures.

2.2.4. All these measures can be considered as part of Crisis Planning. Another important, but often left out, part is the Risk Assessment. According to the Oxford dictionary:

“Risk assessment; a systemic process of evaluating the potential risks that may be involved in a projected activity or undertaking.”

2.2.4.1. In a Risk Assessment, the potential threats are identified and described, an estimate is made of the likelihood and consequences of the occurrence and the acceptability of the risk is described. Based on this, mitigating measures can be taken. Risk assessment is a more pro-active way of dealing with a crisis situation, but cannot solve every issue beforehand.

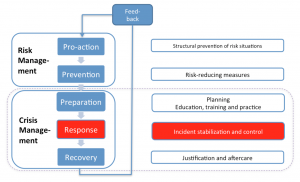

2.2.5. The distinction between risk management and crisis management is shown in the diagram below. The Safety Chain is used by the government of The Netherlands, to define the mandatory elements of safety policy for organisations. This model is based on the Emergency Management Phases (USA Federal Emergency Management Agency, FEMA).

The Safety Chain ((Veiligheidsketen), Government of The Netherlands, 1993 (translated for use in this paper))

2.3. Managing crisis situations

The OCIR method

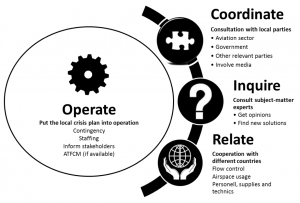

2.3.1. In all three phases of Crisis Management (preparation, response and recovery), it is important to work and think in a systematic manner. The first reaction to any disruption should be to act as quickly as possible and to (continue the) work according to the crisis and contingency plans. However, recent crises have made it clear that there are many benefits when consultation and cooperation with third parties are initiated simultaneously. This approach can be divided into four steps, summarized in the model below.

OCIR model (Model for ATM Crisis Response) (R. Pauptit & S. Verpalen, 2014)

2.3.2. Operate

The local contingency plan is put into operation. This should include, but is not limited to actions related to contingency, staffing, inform internal and external stakeholders and perform risk analysis, all on a local level.

The main purpose of the operating phase is to continue the safe and orderly flow of traffic. This is the most important and continuing step in the OCIR model and mandatory to handle a crisis situation. The three following steps are more in-depth and can, if timely initiated, get a broader view and result in faster and more creative crisis management and solution.

2.3.3. Coordinate

Consultations shall be held with the aviation sector, government and other relevant local parties. Also, the media should be involved: many recent examples have shown that if the media is actively approached, the information flow is more manageable and might be influenced.

2.3.4. Inquire

One or more subject-matter experts can be particularly useful and predictive in any crisis situation. Obviously with natural disasters, but also when an armed conflict, a comprehensive plane crash or an economic crisis occurs. An on-site expert can be of great value. This person can be quickly consulted on changes in the situation and is supportive to a crisis response meeting. In daily operation, many ANSP’s already do this by stationing a meteorologist in the OPS room.

2.3.4.1. Relate

The disruption of services in a particular airspace is likely to significantly affect the services in adjacent portions of airspace. Therefore, co-operation with neighbouring countries is of great importance.

- ANSP’s can prepare crisis management scenarios together, perform risk assessments and make contingency plans, all on a international level.

- ANSP’s should consider how information sharing between states will take place and have communication schemes ready, possibly supplemented by a decision tree. This is a decision support tool that uses a tree-like model of decisions and possible consequences. Part of the effectiveness of the decision tree approach is to allow the development of a strategy independent of scenario.

- In the response phase of a crisis, neighbouring ANSP’s can provide opportunities with regard to flow control, airspace usage, deployment of ATC personnel and the provision of supplies and technics.

Preparation

2.3.4.2. Contingency plans are essential to prepare for- and cope with any crisis situation. Experts, with ATCO’s partaking, should develop and test these plans. Special attention should be given to the simplicity of the procedures to understand and perform, as in crisis situations every second counts. A distinction has to be made between information, which is time-critical and needs to be directly available in the OPS room and information which has to be available but can be looked up.

2.3.5. According to ICAO every air traffic services authority is obliged to have a contingency plan for events of disruption. The main goal is to continue Air Traffic Services and to keep the main ATS routes open if possible. Guidance material for the development, promulgation and implementation is contained in Attachment C of ICAO Annex 11.

ICAO Annex 11 – Air traffic services, Chapter 2:

2.30 Contingency arrangements

Air traffic services authorities shall develop and promulgate contingency plans for implementation in the event of disruption, or potential disruption, of air traffic services and related supporting services in the airspace for which they are responsible for the provision of such services. Such contingency plans shall be developed with the assistance of ICAO as necessary, in close coordination with the air traffic services authorities responsible for the provision of services in adjacent portions of airspace and with airspace users concerned.

Note 2. – Contingency plans may constitute a temporary deviation from the approved regional air navigation plans; such deviations are approved, as necessary, by the President of the ICAO Council on behalf of the Council.

ICAO Annex 17, standard 3.1.3:

“Each contracting State shall keep under review the level of threat to civil aviation within its territory, and establish and implement policies and procedures to adjust relevant elements of its national civil aviation security programme accordingly, based upon a security risk assessment carried out by the relevant national authorities.”

2.3.5.1. Unfortunately, ICAO regional offices report that in many countries no contingency plan is present. If there is any plan available this is often not all robust. Although the regional offices are proactive in promoting the need for proper contingency planning, it’s a low priority issue for many states. In the Asia/Pacific region the Regional Office established the ATM Contingency Plan Task Force (RACP/TF), which is assisting States to create their contingency plans. They also are planning the implementation for a regional ATM contingency plan. Other Regional Offices can help; for instance by providing a Contingency Plan Development Template.

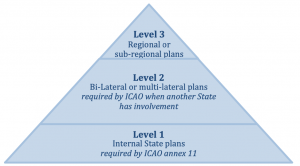

2.3.5.2. The RACP/TF introduced a framework that divides contingency plans into several hierarchical categories and levels.

Level 1: domestic plan, plans that are for internal states only. These plans have little or no effect on external ANSPs. This is the minimum form of contingency planning ICAO requires states to have.

Level 2: also involves other States. These type of contingency plans are required by ICAO if another ANSPs services are significantly affected, for example by re-routing of traffic in case of crisis, or when delegated airspace is used during normal operations.

Level 3: regional or sub-regional plans, which are containing arrangements affecting ANSPs outside the official contingency airspace. The contingency plans of several ANSPs are harmonised. These plans are not required to have by ICAO, but are preferable for an optimized traffic flow in crisis situations.

Hierarchy of contingency plans (Diagram showing the RACP/TP framework levels, RACP/TF/3-Flimsy 1, 2013)

2.3.5.3. As discussed earlier, a crisis almost always has trans boundary effects. ANSP’s should strive to develop a level 3 contingency plan, built up gradually following the OCIR method.

2.3.5.4. In case of a need for a contingency plan, three categories of airspace usage can be defined (“Contingency Planning Review”, RACP/TF/3). The causes, risk and duration vary, but all can have a major impact on ATS. In the first category the airspace might be safe but is restricted, or Air Traffic Service might still be an option. This could be because of an earthquake, industrial action or an ATM system failure. In the second category, the airspace might not be safe and in the third category, the airspace is not available at all. Examples are volcanic ash or a nuclear emergency. This is normally a political decision. A contingency plan should cover all three of these categories.

2.3.5.5. A contingency plan should contain a number of possible scenarios. These scenarios describe possible crisis situations, which are realistic to happen. Each scenario contains a generic description, impact analysis, decision-making principle (who decides what) and possible relevant information. Apart from the primary, strictly necessary parts of a crisis plan, the health and welfare of employees should also be included; initiatives such as Critical Incident Stress Management6 could be adopted.

2.3.5.6. Contingency plans can never cover every possible situation. However, they form a solid foundation and make sure that staff and systems are better prepared. The IFATCA Crisis Guide gives further examples and case studies on how to act in case of a crisis situation.

2.3.5.7. Crisis and contingency plans must be continuously updated and trained. Information within the plans should always be valid. The training of crisis plans is not only important to keep controllers current, but should also be seen as a part of a continuous enhancement process. These trainings should involve all aspects of the plan.

2.3.5.8. The IFATCA Technical & Professional manual contains the following policy on emergency training:

|

Emergency training, including In Flight Emergency Response (IFER) and coordination training, handling of Unlawful Interference situations and Hypoxia awareness should be part of ab-initio and refresher training. Controllers should be given initial and recurrent training in the degraded mode operations of their equipment. Whatever the ATC environment, controllers should receive suitable, regular training on the published back-up procedures, which would be put into operation in the event of a system failure. |

This policy has some repetitive elements in regard to degraded mode training: the Cairo policy is broadly a repeat of the second policy. Emergency and degraded systems training can be categorised together as mandatory training for disruptive events, while the specific training elements, such as IFER and hypoxia awareness, are advisable to have the most complete training programme. It’s proposed that the policy is replaced by:

Air Traffic Controllers shall be regularly trained in emergency and degraded system situations, in ab-initio as well as recurrent training.

This training should at least include In Flight Emergency Response (IFER) and coordination training, handling of Unlawful Interference situations, Hypoxia awareness, and contingency procedures.

Response

2.3.6. The response phase is a strategic, tactical and operational phase is which the crisis is handled in accordance with published and trained plans.

2.3.6.1. ICAO Annex 11, Attachment C (Material Related to Contingency Planning) describes basic solutions that can be considered after a crisis has occurred. Most of these solutions will only be possible, or be far more effective, when neighbouring states cooperate. ANSP’s should communicate with other states as soon as possible, to find joint possibilities and make agreements.

2.3.6.2. According to ICAO Annex 11, Attachment C, the most important short-term solutions to congestion of air traffic or airspace closure, which can be achieved by cooperating, are:

a) re-routing of traffic to avoid the whole or part of the airspace concerned, normally involving establishment of additional routes or route segments with associated conditions for their use;

b) establishment of a simplified route network through the airspace concerned;

c) reassignment of responsibility for providing air traffic services in airspace over the high seas or in delegated airspace;

d) provision and operation of adequate air-ground communications, AFTN and ATS direct speech links, including reassignment, to adjacent States, of the responsibility for providing meteorological information and information on status of navigation aids;

e) special arrangements for collecting and disseminating in-flight and post-flight reports from aircraft;

f) a requirement for aircraft to maintain continuous listening watch on a specified pilot- pilot VHF frequency in specified areas where air-ground communications are uncertain or non-existent and to broadcast on that frequency, preferably in English, position information and estimates, including start and completion of climb and descent;

g) a requirement for all aircraft in specified areas to display navigation and anti-collision lights at all times;

h) a requirement and procedures for aircraft to maintain an increased longitudinal separation that may be established between aircraft at the same cruising level;

i) a requirement for climbing and descending well to the right of the centre line of specifically identified routes;

j) establishment of arrangements for controlled access to the contingency area to prevent overloading of the contingency system; and

k) a requirement for all operations in the contingency area to be conducted in accordance with IFR, including allocation of IFR flight levels, from the relevant Table of Cruising Levels in Appendix 3 of ICAO Annex 2, to ATS routes in the area.

2.3.6.3. ATFCM (Air Traffic Flow and Capacity Management) can be highly effective in regulating air traffic in times of low capacity. Regulating traffic can avoid exceeding airport or ATC capacity and absorb delay when traffic is still on the ground, preventing unnecessary holding and ATC workload Flow control has proven itself in Europe (CFMU) and America (ATCSCC), not only for small delays, but also when big disruptions occur, such as the Ukraine situation, runway/airport closures or extreme weather conditions.

2.3.6.4. In Europe, the Eurocontrol Network Manager is responsible for the distribution of delay in order to regulate traffic. The Network Manager is also responsible for crisis management. It has a step-by-step approach, including three phases in a network disruption: from (expected) minor network problems or a major European disruption to a major loss of capacity/imbalance between network capacity and demand.

As a tool of the Network Manager, the Network Operations Portal (NOP), allows a common view of the European ATM network situation and enables ANSP’s to anticipate or react more efficiently to a disruption. Furthermore it is used to plan pan-European operations in a collaborative way.

Another Network Manager tool is the European crisis Visualisation Interactive Tool for ATFCM (EVITA). This allows users to visualise the impact of a crisis on air traffic and the available network capacity. The informative tool can help decision-making and supports the information sharing process.

2.3.6.5. ICAO Regional Offices are trying to create a similar concept in the Asia/Pacific Region through the ATFM Steering Group. Although many States have developed ATFM measures for domestic flights, very few currently have procedures for managing international flights. The idea is that ANSPs share the anticipated acceptance rate together on a daily basis. This will then be collected in a ‘virtual’ Sub-Regional ATFM centre. In June 2015 a three-month operational trial of the concept will be tested, based on the outcomes of this trial, other trials are planned.

Recovery

2.3.7. After every major disruption or event, there should be a debriefing with all parties that were involved in the handling of the situation. Every taken step should be reviewed and consolidated, also the ones that did not turn out to be effective in managing the crisis situation. Furthermore, this phase is essential to care for ATM personnel and other people involved.

2.3.7.1. The outcomes of the event and the debriefing can be used to improve crisis- and contingency plans of the ANSP (Plan Do Check Adjust – PDCA Cycle). Also, the information should be shared with other ANSP’s to get a global idea of effective measures and possible opportunities in crisis management.

Conclusions

3.1. Although according to ICAO every air traffic services authority is obliged to have a contingency plan for events of disruption, ICAO regional offices report that many states don’t have a contingency plan, that is regularly updated, in operation

3.2. Over the past years several international projects took place in order to reinforce and enhance the level of contingency plans. The TF-RCZ is working to establish a framework to identify, assess, share information to respond to risks to civil aircraft from activities in conflict zones.

3.3. The RACP/TF divides contingency plans into three hierarchical categories. Although a level 1 (Internal State Plan) or level 2 (bi-lateral or multi-lateral plan) are the only that are obliged to have by ICAO, States should strive for a Level 3 (Regional or Sub-Regional) plan.

3.4. Communication, especially across the border, can provide many opportunities in finding short-term solutions to cope with traffic overload.

3.5. ICAO has published several short-term solutions to congestion of air traffic of airspace closure in Attachment C of Annex 11.

3.6. Although several definitions exist, it’s not always clear when a situation is a crisis. A new definition, specified for Air Traffic Management, is proposed in this paper, and a distinction between types of crises (cause, risk, impact and duration/recovery) in ATM is made.

3.7. Crisis Management can be divided into three categories, namely Preparation, Response and Recovery.

3.8. The OCIR (Operate-Coordinate-Inquire-Response) model can help to work and think in a systemic matter in all phases. Including this model in both the preparation and response phase can optimize decision-making.

3.9. The IFATCA Crisis Response and Planning Guide can be used as a guideline by Member Associations to help in the process of dealing with events which could be categorized as a crisis or which could evolve into a crisis. At the moment, the guide is not up-to-date: it lacks a foundation and information the aviation community has learned from recent crises and other disruptions in ATS.

Recommendations

4.1. It is recommended that the following definition is included in the IFATCA Technical and Professional Manual:

Crisis: state of inability to provide air navigation service at required level, affecting system and/or personnel, following an unusual or unforeseen situation.

4.2. It is recommended that the following is deleted from the IFATCA Technical and Professional Manual:

Emergency training, including In Flight Emergency Response (IFER) and coordination training, handling of Unlawful Interference situations and Hypoxia awareness should be part of ab-initio and refresher training.

WP 94 – Amman 2011

Controllers should be given initial and recurrent training in the degraded mode operations of their equipment.

WP 161 – Arusha 2008

Whatever the ATC environment, controllers should receive suitable, regular training on the published back-up procedures, which would be put into operation in the event of a system failure.

Cairo 81, C.24, edited Istanbul 2007

and is replaced with :

Air Traffic Controllers shall be regularly trained in emergency and degraded system situations, in ab-initio as well as recurrent training.

This training should at least include In Flight Emergency Response (IFER) and coordination training, handling of Unlawful Interference situations, Hypoxia awareness, and contingency procedures.

4.3. It is recommended that IFATCA policy is:

Air traffic controllers should be involved in the development of contingency and crisis management plans. This includes regional and sub-regional contingency plans. IFATCA supports the OCIR model for the development of such procedures. Contingency plans should be regularly updated.

And is included in the IFATCA Technical and Professional Manual.

4.4. It is recommended that:

IFATCA Crisis Response and Communications Planning Guide is reviewed and/or updated.

References

IFATCA Technical & Professional Manual, 2014.

IFATCA 08 WP#174, Crisis Guide.

Crisis Response and Communications Planning Guide – IFATCA, February 2008.

IFATCA Meeting Report ATFMSG/4 – John Wagstaff, December 2014.

Contingency and Emergency Plans in Aviation: the IFATCA View – Zeljko Oreski, November 2011.

ICAO Doc 7300.

ICAO Annex 11, Air traffic Services.

ICAO Annex 17, Security.

ICAO Crisis Management Framework, drafted version 4 October 2014, paragraphs 1.1/1.2 and 2.2.3.1/2.2.3.2/2.2.3.3.

“Report from the senior-level Task Force on Risks to civil aviation in Conflict Zones” – ICAO Council 203rd session, appendix A (Chairman’s report), C-WP/14220, September 2014.

Aviation Security Global Risk Context Statement, 3rd edition– ICAO, March 2014.

“Contingency planning review” – RACP/TF/3, November 2013.

“MID region ATM Contingency Plan”, WP9- MIDANPIRG ATM/AIM/SAR SG/13 October 2013.

ICAO Global RCS presentation – Regional Seminar on Aviation security, Lima, June 2013.

ICAO HCLAS-WP/10 “Global Risk Context Statement” – September 2012.

Regional ATM Contingency Plan, agenda item 3, 47th Conference of Directors General of Civil Aviation Asia and Pacific Regions – Macao, October 2010.

“ICAO documentation related with contingency plans” – ICAO SAM Regional Office ATM/CNS WP/04, September 2010.

Crisis management framework draft, EANPG, 2014.

NOP Factsheet – Eurocontrol internal publication 2014.

ICAO ANC12 WP “Regional crisis management and coordination” – European Union, European Civil Aviation Conference and Eurocontrol, November 2012.

Guidelines for Contingency Planning of Air Navigation Services edition 2.0 – Eurocontrol, 2009.

European Aviation Crisis Coordination Cell EACCC – Eurocontrol, https://www.eurocontrol.int/articles/european-aviation-crisis-coordination-cell-eaccc

Eurocontrol Network Manager, https://www.eurocontrol.int/articles/about-network-manager

ATC Crisis Management Training pays off – Dick van Eck. Aerosafetyworld, November 2009 Aspects of International Co-operation in Air Traffic Management, W. Schwenk / R. Schwenk, 1998, Kluwer Law International.

Oxford Dictionary.

Contingency Planning vs. Crisis Management – Tom Gresham, The Herald Chronicle.

Crisis management, Volume II – Sage Library in Business and Management, 2008.

Quality Circle (PDCA Cycle), W.E. Demming.

With special thanks to:

Chris Dalton, ICAO chief ATM

Leslie Cary, ICAO

Leonard Wicks, ICAO Bangkok Office

Sven Halle, ICAO Paris Office

John Wagstaff, IFATCA Asia/Pacific Representative

Peter Chadwick, Hong Kong Civil Aviation Department

Wim Holthuis, ATC The Netherlands (LVNL) Crisis Manager