DISCLAIMER

The draft recommendations contained herein were preliminary drafts submitted for discussion purposes only and do not constitute final determinations. They have been subject to modification, substitution, or rejection and may not reflect the adopted positions of IFATCA. For the most current version of all official policies, including the identification of any documents that have been superseded or amended, please refer to the IFATCA Technical and Professional Manual (TPM).

56TH ANNUAL CONFERENCE, Toronto, Canada, 15-19 May 2017WP No. 83Ambient Workplace RecordingPresented by PLC and TOC |

Summary

Many Member Associations (MAs) are confronted with their ANSPs considering the implementation of Ambient Workplace Recording (AWR), following the ICAO recommendation (2006) or a recommendation of their local safety investigation board. A recent EASA proposal to make AWR a requirement has shook up the European region.

AWR captures background voice communication in an operational environment and is aimed to aid incident and accident investigation, providing a context that is not available from other information sources. The technical concept is fairly simple and comparable to a cockpit voice recorder. However, the system raises severe privacy and liability issues, while MAs where AWR is in place report that the benefit for safety may be overestimated.

IFATCA calls on ANSP’s to first investigate, together with MAs, if the predicted benefits of AWR outweigh the potential hazards. If such a system is implemented nevertheless, clear procedures shall be in place with respect to privacy, access to recordings, usage of recordings, storage time and filtering of non-relevant information.

This paper gives guidance, examples and updates to IFATCA policy on the use of recorded data.

Introduction

1.1 Many Member Associations (MAs) struggle with the implementation of Ambient Workplace Recording (AWR) by their Air Navigation Service Providers (ANSPs). Some countries have rejected the technology, whilst others have had AWR systems in place for years.

1.2 Information and user reports about the implementation and operation of AWR around the world is available through an IFATCA Questionnaire (2016) and an inquiry by ATC The Netherlands (LVNL) for CANSO (2015, updated 2016).

1.3 The rationale for the implementation of AWR is often based on a recommendation by a public transport board after an incident or accident. Reference is generally made to the ICAO recommendation in Annex 11 on this matter (2006).

1.4 While AWR is intended for the sole purpose of assisting incident and accident investigation, it raises privacy and liability issues.

1.5 In 1994 IFATCA drafted policy on Area Recording, as part of Accident and Incident Investigation policies. The broader subject was reviewed and amended in consecutive years. Policy on Area Recording has remained the same.

1.6 In this working paper, TOC and PLC aim to redefine the concept of AWR, assemble experiences with (implementation of) the system from all over the world, review current IFATCA policy and, if necessary, update this policy with regard to existing principles on Automatic Safety Monitoring Tools (ASMT) and Automated Data Recording.

1.7 It should be noted that the protection of recorded information might as well be subject to national legislation.

Discussion

2.1 The desire to record background communications

2.1.1 Area Recording can generally be described as “any type of recording, audio and/or visual, instituted in an air traffic control operations room that accurately records the conversation of controllers and the environment within an air traffic control operations room on a continuous basis.” (Ottawa, 1994).

2.1.2 There is no clear definition of Ambient Workplace Recording (AWR). At this moment, the ICAO Safety Management Panel (SMP) is discussing this issue. This paper is specifically focused on audio background communications and the aural environment, excluding the use of video. The Cockpit Voice Recorder (CVR) is another example of AWR (ICAO, Annex 13/19, 2006).

2.1.3 The purpose of AWR is to improve aviation safety by assisting in incident and accident investigations. Not all verbal exchange of information is captured through the voice communication system in the OPS room. For example, ATCOs working in close proximity may sometimes coordinate without using the voice communication system.

2.1.4 Following the Überlingen mid-air collision in 2002, the German BFU investigation board published the following recommendation:

| “To improve the investigation of future accidents and incidents ICAO should require ATS units -in addition to present regulations – to be equipped with a recording device that records background communication and noises at ATCO workstations similar to a flight deck area microphone system.” |

(German Federal Bureau of Aircraft Accidents Investigation (BFU), Investigation Report AX001-1-2/02 – May 2004)

2.1.5 No requirement, but a recommendation came into place in 2006 when ICAO adopted an amendment to Annex 11 (Air Traffic Services), recommending that:

| “Air traffic control units should be equipped with devices that record background communication and the aural environment at air traffic controller work stations, capable of retaining the information recorded during at least the last twenty-four hours of operation.” |

(ICAO Annex 11 Air Traffic Services, Chapter 3 Air Traffic Control Service, paragraph 3.3.3 – Thirteenth Edition July 2001, amended 2006)

2.1.6 According to ICAO, the recommendation was made because:

| “(…) in unfortunate circumstances word may stand against word as to exactly what transpired at a given moment. This would include exchange of verbal information that takes place between controller/supervisor, controller/maintenance engineer and between controller/controller. The recording of background communication and the aural environment at controller work stations may contribute to a better understanding of the sequence of events leading to an accident or incident.” |

(ICAO AN-WP/8041 Appendix A: “Summary of replies to state letter AN 13/1.8, AN 13/13.5, AN 6/1.2-04/93”)

ICAO’s recommendation was inserted into Civil Aviation Regulations of many countries worldwide.

2.1.7 In the following years several Investigative Boards recommended the actual implementation of AWR, referring to the ICAO recommendation. Examples are:

– Luxembourg, 2010 (final report 2012): collision of a Cargolux B747-400F with an unoccupied van, before touching down on the runway. Amongst the many recommendations, also was: “that ANA (the ANSP) should implement the recommendation by the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) in Annex 11 Air Traffic Services, paragraph 3.3.3. (…).” [LUAC-2012/002] (Luxembourg Ministry of Sustainable Development and Infrastructure, Department of Transport, Report N° AET-2012/AC-01 – December 2012)

– Frankfurt, 2011 (final report 2012): loss of separation between Aeroflot A320 taking off and Lufthansa A388 going around on parallel runways. Recommended was: “that The Federal Ministry of Transport, Building and Urban Affairs (BMVBS) should pass a decree regarding the implementation of the ICAO recommendation in Annex 11, Chapter 3.33. Based on this decree the air traffic service providers should (…)” [38/2012] (German Federal Bureau of Aircraft Accidents Investigation (BFU), Investigation Report 5×013-11– 2012)

– Amsterdam, 2012 (final report 2015): nine take-offs from an unavailable runway. One of the three recommendations from the Dutch Safety Board to the ANSP was: “give effect to the ICAO recommendation to also capture the background conversations at air traffic control units.” (Dutch Safety Board (OvV), Nine take-offs from an unavailable runway, 16 June 2012 Amsterdam Airport Schiphol – June 2015)

2.2 Existing policy and regulations

2.2.1 ICAO

The following text on AWR is implemented in ICAO documents:

| CHAPTER 3. AIR TRAFFIC CONTROL SERVICE 3.3 Operation of air traffic control service

3.3.3 Recommendation. — Air traffic control units should be equipped with devices that record background communication and the aural environment at air traffic controller work stations, capable of retaining the information recorded during at least the last twenty-four hours of operation. Note. — Provisions related to the non-disclosure of recordings and transcripts of recordings from air traffic control units are contained in Annex 13, 5.12. |

(Amendment 44 ICAO Annex 11 (2006))

| LEGAL GUIDANCE FOR THE PROTECTION OF INFORMATION FROM SAFETY DATA COLLECTION AND PROCESSING SYSTEMS7. Protection of recorded information

Considering that ambient workplace recordings required by legislation, such as cockpit voice recorders (CVRs), may be perceived as constituting an invasion of privacy for operational personnel that other professions are not exposed to: a) subject to the principles of protection and exception above, national laws and regulations should consider ambient workplace recordings required by legislation as privileged protected information, i.e. information deserving enhanced protection; and b) national laws and regulations should provide specific measures of protection to such recordings as to their confidentiality and access by the public. Such specific measures of protection of workplace recordings required by legislation may include the issuance of orders of non-public disclosure. |

(ICAO Annex 13, Attachment E)

| PRINCIPLES FOR THE PROTECTION OF SAFETY DATA, SAFETY INFORMATION AND RELATED SOURCES 6. Protection of recorded data

Note 1.— Ambient workplace recordings required by national laws, for example, cockpit voice recorders (CVRs) or recordings of background communication and the aural environment at air traffic controller work stations, may be perceived as constituting an invasion of privacy for operational personnel that other professions are not exposed to. Note 2. — Provisions on the protection of flight recorder recordings and recordings from air traffic control units during investigations instituted under Annex 13 are contained therein. Provisions on the protection of flight recorder recordings during normal operations are contained in Annex 6. 6.1 States shall, through national laws and regulations, provide specific measures of protection regarding the confidentiality and access by the public to ambient workplace recordings. 6.2 States shall, through national laws and regulations, treat ambient workplace recordings required by national laws and regulations as privileged protected data subject to the principles of protection and exception as provided for in this appendix. |

(ICAO Annex 19, appendix 3 (EFFECTIVE NOV 2016))

2.2.2 The ICAO Safety Management Panel (SMP) is at this time discussing AWR, with the next meeting scheduled in January 2017. One of the goals is to come up with a global definition of what AWR, or background voice recording, entails.

2.2.3 SERA

The Standardised European Rules of the Air (SERA) that took effect across Europe in 2014, does not mention AWR; the ICAO recommendation was not incorporated.

2.2.4 EASA

In September 2016, EASA proposed a Notice of Proposed Amendment (NPA 2016-09), in which a requirement for the recording of background communications is proposed:

| (proposed) ATS.OR.465 Background communication and aural environment recording Air traffic control units shall be equipped with devices that record background communication and the aural environment at air traffic controller work stations, capable of retaining the information recorded during at least the last 24 hours of operation. |

2.2.5 This proposal originates from the ICAO recommended practice in Annex 11. The text is almost the same as ICAO Annex 11, with the important difference that that the requirement is mandatory instead of a recommendation – indicated by the word ‘shall’ instead of ‘should’. According to EASA:

“ICAO does not provide guidance on the scope and implementation of this requirement, and evidence gathered by the Agency with the contribution of the RMG.0464 members suggests that the majority of the EU Member States has not yet implemented this provision, and that even when they have, there is a great diversity in the way it is implemented.”

EASA stakeholders, including IFATCA, are able to comment on this proposed regulation until the end of February 2017.

2.2.6 IFATCA

The first IFATCA guidelines on the use of recorded information date from 1989, and the first policy on AWR was adopted in 1994. The term used was ‘Area Recording’. Since 1994, the policy has not been changed:

| Audio, visual and area recordings, together with associated computer data and transcripts of air traffic control communications are intended to provide a record of such communications for use in the monitoring of air traffic control operations, and the investigation of incidents and accidents. Such recordings are confidential and are not permitted to be released to the public. Such recordings are not to be used to provide direct evidence such as in disciplinary cases, or to be used to determine controller incompetence. 2.6.2 Except for area recordings, recorded data shall only be used in the following cases:

a) when investigating ATC related accidents and incidents; b) for search and rescue purposes; c) for training and review purposes provided all ATCOs affected agree; d) for the purposes of adjusting and repairing ATC equipment. Area recordings shall only be used for accident investigation purposes. An area recording may generally be defined as any type of recording, audio and / or visual, instituted in an air traffic control operations room that records accurately the conversation of controllers and the environment within an air traffic control operations room on a continuous basis. Access to recorded data shall be limited to authorised personnel for the purposes listed in 2.6.2 above. Authorised personnel shall be mutually agreed by the controllers’ representative and the appropriate authority. Recorded data used shall be identical as presented to and / or originated by the controller at the relevant controller’s position. IFATCA is opposed to the use of Visual Area recordings for reasons of invasion of privacy. Prior to the installation of Area recorders, legislation shall be in place which prohibits the use of any area recorder information against a controller in any criminal or civil litigation or disciplinary proceedings of any kind. The legislation should provide for substantial penalties for any breach of the legislation. Except when an accident occurs, area recordings shall be capable of being erased when a controller is relieved from his position. Controllers shall have prompt confirmation of the erasure. Agreement between the Member Association and the employer on procedures for the erasure of area recordings shall be established prior to the operation of area recorders. |

(IFATCA Technical and Professional Manual 2016 edition – LM11.2.6 Use of recorded data)

2.2.7 The policy could be improved in several ways. First of all, the definition of AWR is not yet included; it should be distinguished from Area Recording in general, which also includes video. Secondly, the policy is fragmented and not in a logical order.

2.2.8 The paragraph on access to recorded data refers to a list of goals that starts with the precondition that it is not valid for background recordings. Lastly, the current recommendation for erasing of recordings is not practicable. Deleting the information as soon as an ATCO is relieved from the working position, may be too fast. It can take longer until an incident is recognised and incident investigator is initiated.

2.3 AWR implementation around the world

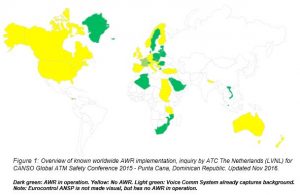

2.3.1 Figure 1 gives an overview of known countries that have AWR in operation (green colour) or do not work with AWR (yellow colour), up to November 2016. An inquiry by ATC The Netherlands (LVNL), performed for CANSO, has resulted in this overview.

2.3.3 IFATCA TOC and PLC issued a questionnaire on the subject of AWR in September/October 2016. 22 Member Associations (MA’s) from all continents responded. MA’s were asked if AWR is currently in operation and if not, what were the reasons for it. Also, individual ATCO’s were requested to give their opinion on the advantages and disadvantages of the concept. The main results are:

In three of 22 responding countries, AWR is currently in operation: South Africa, Switzerland and Algeria. For the countries that do not have AWR in operation, one or more of the following factors caused this:

- MA reacted against it (33.3%)

- Management decision (27.8%)

- Technical issues (11.1%)

- Other, e.g. AWR not considered yet (50%)

2.4 Advantages and disadvantages of AWR

2.4.1 According to the respondents on the IFATCA survey, the main advantage of AWR are that it can aid safety investigations by providing a context that is not available in other information sources, such as radiotelephony recordings. Listening to background recordings can provide greater insight into the operational environment, especially when analysing verbal coordination between operational personnel that is not conducted via a voice communication system. Examples are quick verbal agreements between sectors (“You can descent with flight …”) or in a tower environment (“You can cross runway … with flight … / vehicle …”). Coordination between ATCO’s and supervisors, assistants and technical personnel are other cases that background recordings can capture. This can help safety investigators to better understand what exactly happened.

2.4.2 User reports from our survey show that an operational AWR system raises several issues. It is arguable whether the utility of AWR is being overestimated, particularly by transport safety boards and management. There is so much data already available that a clear and sufficient understanding of an incident can often be accomplished without the call for background communications. Per one of the respondents:

“The principle of commensuration needs to apply (…) nearly all coordination and inputs are already recorded; hardly any benefit in our system can be derived by AWR. The only use will be to blame the individual”.

2.4.3 In a busy operational environment, especially a control tower, it may be a challenge to capture all the communication clearly and to determine what is said by whom. Coordination between ATCO’s is often carried out non-verbally, for instance by hand signals or eye contact. Technical challenges will be discussed in paragraph 2.5.

2.4.4 The most discussed disadvantages of background communication recording are privacy and Just Culture issues. ATCO’s describe an uncomfortable working situation, where controllers (could) refrain from saying what they want or must say when they know they are recorded. An ATCO reports having seen multiple workarounds and tampering with the system: “I have seen everything from paper cups to teddy bears over the microphones at a previous employer.” This topic is discussed separately in paragraph 2.6.

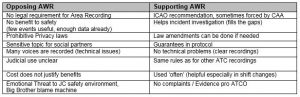

2.4.5 In the investigation for CANSO, countries that considered implementation were asked for reasons why this was successful or unsuccessful (Inquiry by ATC The Netherlands (LVNL) for CANSO Global ATM Safety Conference 2015 – Punta Cana, Dominican Republic):

2.5 Technical challenges

2.5.1 The imperatives attached to the Cockpit Voice Recorder (CVR) as a feature on the cockpit to aid aircraft accidents/incidence investigation from as far back in the 1950s has necessitated extensive researches and experiments into it, and by far surpass any done on AWR which is relatively new. This bias has created a dearth of information on AWR. The consequence of this is a difficulty in gathering materials of technical nature directly from researches done on AWR. Subsequently, the technical perspective of this working paper has so much leaning on the similarities between CVR and AWR. What exists in CVR and what is required of AWR were carefully studied especially in terms of problems arising from installation of CVR system a lot of information applicable to AWR emerged.

2.5.2 AWR like its counterpart, the CVR, is a system installed within the operational Air Traffic Control workspace to capture all sound that will be of benefit for the purpose of investigating a reportable accident or incident. For that purpose, the quality of the recording should provide for a high level of intelligibility of speech and background noise audible within the workspace or area of coverage.

2.5.3 The basic idea of the system behind AWR is not very complex. As a manufacturer of aural environment recording states:

“In most cases this can be achieved easily by adding additional channels to your existing audio recording system. (…) An entry level solution is to upgrade your existing audio recorder to capture an extra audio channel for each Controller Workstation Position, with microphones placed as near as sensibly possible to the ATCO’s sitting position. (…) A future-proof solution is to allow additional audio channels for microphones to be placed not only at CWP’s but also throughout the air traffic control room” (White Paper: Aural Environment (Ambient) Recording, Ultra Electronics AudioSoft, 2008)

2.5.4 Other design elements are a good placement of the microphones (electro-acoustical design of the operations environment), digital noise-cancelling signal processing and a storage system which meets the requirements of information security and redundancy.

2.5.5 It is imperative that to maximise the advantage to investigation offered by this system, Workspace Area Microphones (WAM) need to be installed at strategic positions, each on a different channel. Systems associated with capturing background noise in order to extract intelligibility generally suffer from the following problems:

- Poor quality of the recording due to under-performing pre-amplifiers;

- Poor quality of the recording due to insufficient sensitivity of the Workspace Area Microphone (WAM);

- Wrong installation of the WAM;

- Excessive background noise due to incorrect shielding of the WAM audio wiring;

- Signal cancellation when signals of opposite phase signs are mixed.

- Saturation of the recording on certain channels by low frequency vibrations due to excessive sensitivity of the WAM.

To address the above problems a need for understanding some vital components of AWR must be stressed upon.

Components of the AWR system

2.5.6 Microphone

In the context of discussing AWR, reference to microphone will be in terms of Workspace Area Microphone (WAM) as a semblance of Cockpit Area Microphone (CAM). WAM is the key device that allows the capture of fluctuations of the vocal cords. The output signals from the WAM varies in intensity and quality which is often fed out to be processed to desired output. Dynamic and Condenser mic(s) are types of microphone to consider. Whereas dynamic mic has strong diaphragm to absorb heavy noise, the condenser type should suffice as type adequate for inclusion in AWR due its ability to record subtle nuances in sounds, although not as robust as the former.

2.5.7 Room Acoustic

This refers to the size of the room, the orientation, smoothness and roughness of the walls and other room components, etc. All these affect how sound waves will bounce around into the WAM creating delays, reverbs, constructive and destructive interference at various frequencies, and a multitude of other problems like flutter and so on. Acoustics could be subdued or treated through the use of reflection panels, clouds, bass traps, diffusors etc.

Implementation of the AWR system

2.5.8 In a CVR system the Cockpit Area Microphone carrying audio signals from the pilot in command, first pilot and another are usually paired with pilot-ATC, pilot-pilot microphone etc. to be eventually channelled separately for storage. Extra CAM are strategically positioned within the cockpit for optimum capturing of desired signals.

2.5.9 While installing WAM for AWR system installation, it is expected that, due to uniqueness of every ATC operations workspace, a study of peculiarities needs to be done. In addition, noise reduction procedures by personnel with access to such workspaces need to be in place and adhered to.

2.5.10 Regulation of AWR system from specified components, to installations and including what entity (it may be a designated institution) that is qualified to retrieve and analyse untreated or unedited recording is necessary for the sake of uniform implementation as is the case with CVR.

2.6 Privacy and legislation

2.6.1 Of the 22 MAs responding in the IFATCA questionnaire, 84% is of the opinion that AWR affects the privacy of an air traffic controller. It is clear that, when on duty, the ATCO is not in a public environment. Depending on national laws, background recordings could eventually be released to the public. When the recordings are used by a national transport investigation board or in court, it is likely that the data cannot be protected, even while measures of protection are required by ICAO (Annex 11, 13, 19) or even more stringent supra-national or national regulation.

National laws and Just Culture

2.6.2 The responses on the questionnaire demonstrate the anxiety for privacy issues. In the opinion of the ATCOs the possibility for misuse is tremendous. A public piece of recording with controllers talking about non-work related issues, could easily be placed in another context. Something similar has occurred in the past when Cockpit Voice Recordings were published in the media. As indicated in paragraph 2.4, this anxiety can lead to controllers being very cautious in having personal conversations in the workplace and a tense atmosphere that is not benefiting the work ethic.

2.6.3 The Just Culture principle entails that investigations on incidents will only be performed to improve aviation safety and not to put blame on anyone involved. With AWR balancing on a line between invading privacy and improving safety, it is essential that the safeguards rooted in the Just Culture concept are respected when ANSPs choose to implement the system.

2.6.4 In Switzerland, the aviation law was changed in order to be compliant with the requirement of the data protection delegate of the Swiss government. A legal basis was especially created to implement the AVRE (Ambient Voice Recording Equipment) at Swiss ANSP Skyguide.

2.6.5 The New Zealand law was amended in 1999 to protect the confidentiality of CVR recordings, but failed to protect analogous ATC recordings. A recent analysis by the Australian and New Zealand Law Association states that it is

“not satisfactory that on the one hand Annex 13 creates a presumption of non-disclosure of ATC Recordings, whereas the New Zealand Official Information Act creates a presumption of availability of such information.” (Murray, Kim — “The Confidentiality of Air Traffic Control Recordings?”, The Ron Chippindale Address to the Australian and New Zealand Societies of Air Safety Investigators, 2011 Regional Air Safety Seminar Wellington, 10-12 June 201” [2011] ANZAvBf 20; (2011) 57 Aviation Law Association of Australia and New Zealand Aviation Briefs 18)

Access, storage time and deleting personal conversations

2.6.6 Another very important question is who should have access to the recordings within the ANSP. While AWR recordings could be beneficial to any investigation, it is highly debatable if they should be used for internal incident investigations. Being significantly detrimental to the privacy of controllers, arguably only significant incidents with independent investigators involved could justify its use. Incident investigation within the ANSP is often performed by fellow ATCOs or even management – possibly leading to confidentiality and privacy issues. It might even be the case that management uses recordings to avoid blame on themselves. A possible solution is to release background recordings only to an independent investigator, such as a transport safety board. Another option is to use AWR recordings only for internal investigations, only when at the same time an external investigation is initiated. This entails that AWR recordings will only be used for incidents with a certain degree of severity. Management should never have direct access to AWR recordings.

2.6.7 To secure the privacy of ATCOs, personal information in aural recording could be stripped before the recording is released to anyone. This should be done by a person who is separate from the operation, but has sufficient knowledge of air traffic control to filter the recordings. To date we have not encountered an MA where this is in effect, but the gains for protecting the privacy of controllers is obvious. This might also be a way to use the background communication for internal incident investigation. In addition, AWR transcripts shall be stripped from non-relevant conversation before being published in any way.

2.6.8 The storage time of AWR recordings is important to consider as well. For privacy reasons, recordings should be deleted as soon as possible after it has become clear that no incidents occurred in the recorded timeframe. Cockpit Voice Recordings can be erased (scrambled) by the pilots immediately after finishing an uneventful flight. For air traffic control, this is a bit more complicated. It may be not immediately clear that an incident occurred, or if a certain recorded period prior or after an incident is interesting to investigate. Therefore, a longer storage period seems reasonable to secure recordings for investigation. ICAO Annex 11 recommends a minimum of 24 hours; storage time could be extended as a result of national regulations. As long as privacy and access to the recordings are well organised, the actual storage time is less relevant.

2.6.9 The implementation and use of the AVRE system in Switzerland follows a strict protocol. The sole purpose is to serve investigations on accidents or serious incidents by the Swiss Transportation Safety Investigation Board to improve aviation safety. Beyond that purpose the recordings can only be accessed for maintenance reasons. Confidentiality applies to anyone involved in installing and maintaining the system, with sanctions for misuse. A separate authority, accepted by both the Unions and the ANSP, is the neutral owner of the data (including user management and access rights). This entity is called ‘Authority of Trust’.

Conclusions

3.1 A growing number of ANSPs is considering the implementation of AWR, as a result of the ICAO recommendation to do so (Annex 11, 2006) or because of recommendations from their national transport investigation board.

3.2 The main advantage of AWR is that it can aid safety investigations by providing a context that is not available from other information sources.

3.3 The technical concept of AWR is fairly simple and can be compared to a cockpit voice recorder; however, as ATC workplaces often contain many more people than are in a cockpit it may be a challenge to accurately record and distinguish between conversations.

3.4 While AWR is intended for the sole purpose of aiding incident and accident investigation, it raises privacy and liability issues. ICAO Annex 19 prescribes that measures should be taken to protect recorded data regarding the confidentiality and access by the public. In reality, it is known that national privacy laws often conflict with these confidentiality requirements.

3.5 ATCOs working in countries that have experience with the AWR concept, report that the advantage of the system may be overestimated by safety investigation boards and management. The number of incidents where background communication might be helpful to an investigation appears to be limited and non-verbal agreements are not captured. In return, the existence of AWR can lead to a tense situation where controllers refrain from speaking freely.

3.6 Implementation of AWR can only be considered when a fully endorsed Just Culture System is in place and there is a high level of trust between all involved parties.

3.7 IFATCA calls on ANSP’s to investigate thoroughly, together with the MA’s, if the predicted benefits of AWR outweigh the potential hazards. If such a system is to be implemented, it is essential that a clear procedure is developed with respect to privacy, access rights, storage time and possible filtering of personal conversations.

Recommendations

4.1 It is recommended that the following IFATCA policy:

LM 11.2.6 USE OF RECORDED DATA

Audio, visual and area recordings, together with associated computer data and transcripts of air traffic control communications are intended to provide a record of such communications for use in the monitoring of air traffic control operations, and the investigation of incidents and accidents. Such recordings are confidential and are not permitted to be released to the public. Such recordings are not to be used to provide direct evidence such as in disciplinary cases, or to be used to determine controller incompetence.

2.6.2 Except for area recordings, recorded data shall only be used in the following cases:

a) when investigating ATC related accidents and incidents;

b) for search and rescue purposes;

c) for training and review purposes provided all ATCOs affected agree;

d) for the purposes of adjusting and repairing ATC equipment. Area recordings shall only be used for accident investigation purposes.

An area recording may generally be defined as any type of recording, audio and / or visual, instituted in an air traffic control operations room that records accurately the conversation of controllers and the environment within an air traffic control operations room on a continuous basis.

Access to recorded data shall be limited to authorised personnel for the purposes listed in 2.6.2 above. Authorised personnel shall be mutually agreed by the controllers’ representative and the appropriate authority. Recorded data used shall be identical as presented to and / or originated by the controller at the relevant controller’s position.

IFATCA is opposed to the use of Visual Area recordings for reasons of invasion of privacy. Prior to the installation of Area recorders, legislation shall be in place which prohibits the use of any area recorder information against a controller in any criminal or civil litigation or disciplinary proceedings of any kind. The legislation should provide for substantial penalties for any breach of the legislation.

Except when an accident occurs, area recordings shall be capable of being erased when a controller is relieved from his position. Controllers shall have prompt confirmation of the erasure. Agreement between the Member Association and the employer on procedures for the erasure of area recordings shall be established prior to the operation of area recorders.

is replaced by:

Audio, visual and Ambient Workplace Recording (AWR), together with associated computer data and transcripts of air traffic control communications are intended to provide a record of such communications for use in the monitoring of air traffic control operations, and the investigation of incidents and accidents.

Audio and visual recordings and AWR are confidential are not permitted to be released to the public.

Audio and visual recordings and AWR are not to be used to provide direct evidence such as in disciplinary cases, or to be used to determine controller incompetence.

Except for AWR, recorded data shall be used only in the following cases:

a) when investigating ATC related accidents and incidents;

b) for search and rescue purposes;

c) for training and review purposes provided all ATCOs affected agree.

d) for the purposes of adjusting and repairing ATC equipment.

Access to recorded data shall be limited to authorised personnel. Authorised personnel shall be mutually agreed by the controllers’ representative and the appropriate authority. Recorded data used shall be identical as presented to and / or originated by the controller at the relevant controller’s position.

Recorded Data – Specific policy on Ambient Workplace Recording (AWR):

Ambient Workplace Recording (AWR) may generally be defined as any type of recording, audio and / or visual, instituted in an air traffic control operations area that records the conversation of controllers and the environment within an air traffic control operations room on a continuous basis.

IFATCA is opposed to the use of visual AWR for reasons of invasion of privacy.

AWR shall only be used to aid in incident and accident investigations to improve aviation safety.

The AWR system, including user management and access to the recordings, should be managed by an independent authority within the ANSP, chosen jointly by management and Member Association(s).

Before being published in an incident or accident report, non-relevant information shall be removed from AWR transcripts.

and is added to the IFATCA Technical and Professional Manual.