57TH ANNUAL CONFERENCE, Accra, Ghana, 19-23 March 2018WP No. 92State Aircraft and ‘Due Regard’ OperationsPresented by PLC/TOC |

Summary

ICAO rules are applicable only for civil aircraft. State aircraft – identified by ICAO as military, customs and police services – are not required to comply with these rules but States must, when issuing rules for their State aircraft, have ‘due regard’ for the safety of navigation of civil aircraft.

This working paper will examine the legal basis on which State aircraft operate with ‘due regard’, what ‘due regard’ is, where it applies and what controllers can do if State aircraft operate with due regard in their area of responsibility.

In the appendix to this paper, Duty of Care principles are applied to controller actions when managing State aircraft in the absence of guidance regulations.

Introduction

1.1 Controllers are accustomed to issuing clearances/instructions to pilots operating aircraft in their area of responsibility. Some types of flights are not bound to comply with those clearances/instructions and they may operate contrary to civil aviation rules even when they are operating in non-segregated civil airspace.

1.2 Military, customs and police aircraft – collectively known as State aircraft – are permitted by international agreement to operate contrary to civil aviation rules even when they are operating in non-segregated civil airspace. Controllers cannot exercise control over these State aircraft when they operate contrary to civil aviation rules; however, there are some provisions that are intended to safeguard civil aircraft from State aircraft.

1.3 This paper will examine the legal basis on which State aircraft operate contrary to civil aviation rules in sovereign and international airspace. It will also examine the ways in which State aircraft give ‘due regard’ for the safety of navigation of civil aircraft and find examples of the way in which some States regulate State aircraft operations. The appendix to this paper will use the principles of duty of care to consider appropriate controller actions in the absence of guidance or regulations for handling State aircraft that are operating contrary to civil aviation rules.

Discussion

2.1 State aircraft

2.1.1 The definition of State aircraft was set in article 3 of the Convention on International Civil Aviation signed at Chicago on 7 December 1944 (commonly known as the Chicago Convention), now included in ICAO Doc 7300 which contains the full text agreed at that time. Article 3 of the Chicago Convention expressly excludes State aircraft from ICAO scope of applicability as follows:

| Article 3 Civil and state aircraft:

a) This Convention shall be applicable only to civil aircraft, and shall not be applicable to State aircraft. b) Aircraft used in military, customs and police services shall be deemed to be State aircraft. c) No State aircraft of a contracting State shall fly over the territory of another State or land thereon without authorization by special agreement or otherwise, in accordance the terms thereof. d) The contracting State undertake, when issuing regulations for their state aircraft, that they will have due regard for the safety of navigation of civil aircraft (ICAO 2006, p. 2). |

2.1.2 It is important to highlight that the term ‘State aircraft’ includes military aircraft but it is not limited to it. According to ICAO, aircraft used in customs and police services are also State aircraft (ICAO 2006, p. 2).

2.1.3 ICAO, in Circular 330 Civil/Military Cooperation in Air Traffic Management, recommends a number of best practices for cooperation between civil and military agencies. Circular 330 explains the consequences of the particular wording of Article 3 of the Chicago Convention:

| As a consequence of Article 3, in particular subparagraph 3 (d), States are required to safeguard navigation of civil aircraft when setting rules for their State aircraft. This leaves it up to the individual State to regulate these operations and services, generating a wide diversity of military regulations. However, especially in congested airspace, harmonized regulation is a precondition for a safe, efficient and ecologically sustainable aviation system (ICAO 2011, p. 2). |

2.1.4 Circular 330 explains in detail what roles are performed by military and non-military flights under the title of State aircraft. It also highlights circumstances when State aircraft can be fully compliant (airlift or VIP aircraft) or partially compliant (counter-air missions, aeromedical evacuation, intelligence-surveillance-reconnaissance, unmanned aircraft systems, search and rescue, large-scale exercises, police and customs) with international civil aviation rules, as provided for in ICAO standards and recommended practices (SARPs), and it lists the general expectations for handling such aircraft by an air navigation service provider (ANSP) (ICAO 2011, pp. 17-19).

2.2 Territory and Sovereignty

2.2.1 The way in which State aircraft may operate depends on the airspace in which they are operating. The concepts of territory and sovereignty are key and these are considered in the United Nation Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), 10 December 1982.

| Article 2 Legal status of the territorial sea, of the air space over the territorial sea and of its bed and subsoil

1. The sovereignty of a coastal State extends, beyond its land territory and internal waters and, in the case of an archipelagic State, its archipelagic waters, to an adjacent belt of sea, described as the territorial sea. 2. This sovereignty extends to the air space over the territorial sea as well as to its bed and subsoil. 3. The sovereignty over the territorial sea is exercised subject to this Convention and to other rules of international law. Article 3 “Breadth of the territorial sea” Every State has the right to establish the breadth of its territorial sea up to a limit not exceeding 12 nautical miles, measured from baselines determined in accordance with this Convention (UN 1982, p. 27) |

2.2.2 The Chicago Convention affirms the sovereignty of States over their airspace and defines the extent of the States’ territory in line with those limits set out in UNCLOS:

| Article 1 Sovereignty

The contracting States recognize that every State has complete and exclusive sovereignty over the airspace above its territory. Article 2 Territory For the purposes of the Convention the territory of a State shall be deemed to be the land areas and territorial waters adjacent thereto under the sovereignty, suzerainty, protection or mandate of such State. (ICAO 2006, p. 2) |

2.3 ATS (Air Traffic Services)

2.3.1 Controllers are able to provide ATS to aircraft in their area of responsibility because States have defined the framework within which controllers and pilots must operate. States define airspace classifications, rules of the air etc. that apply within their territorial airspace because, as noted earlier, the Chicago Convention states that:

| Article 1 Sovereignty

The contracting States recognise that every State has complete and exclusive sovereignty over the airspace above its territory (ICAO 2006, p. 2) |

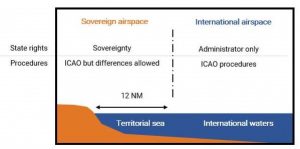

2.3.2 Most states have adopted the ICAO SARPS for the benefit of international traffic; however, as the States retain ‘complete and exclusive sovereignty’ of their airspace, they are free to, and indeed many do, maintain some differences from the ICAO standards. (Although differences are allowed, States are expected to incorporate ICAO standards (Annexes and SARPS) into their national aviation law. Differences must be notified to ICAO and the difference must be published in a supplement to the relevant Annex and also be listed in the State’s aeronautical information publication.)

2.3.3 For the safety and efficiency of international civil aviation, provision of ATS in airspace outside of the territory of States has been assigned in regional agreements. Annex 11 to the Chicago Convention declares that:

| 2.1.2 Those portions of the airspace over the high seas or in airspace of undetermined sovereignty where air traffic services will be provided shall be determined on the basis of regional air navigation agreements. A Contracting State having accepted the responsibility to provide air traffic services in such portions of airspace shall thereafter arrange for the services to be established and provided in accordance with the provisions of this Annex (ICAO 2001, p. 2-1) |

2.3.4 It is important to note that the States that accept the responsibility for providing ATS beyond 12 NM from the coast are only administering that airspace. Clearances/instructions and advice are issued for the safety of civil aviation but it remains international airspace and ICAO requires that ATS in this airspace will be provided in compliance with ICAO standards, regardless of any differences from the ICAO standard that apply in the administering state.

2.4 Due Regard

2.4.1 As seen previously, States issue regulations for civil and for state aircraft too:

| Article 3 Civil and State aircraft

d) The ICAO Contracting States undertake, when issuing regulations for their State aircraft, that they will have due regard for the safety of navigation of civil aircraft (ICAO 2006, p. 2). |

2.4.2 The Chicago Convention demands that the States, when writing their own rules for their State aircraft, ‘take the proper care and concern for’ the safety of navigation of civil aircraft (The Merriam Webster dictionary definition for ‘with due regard to’). These rules may be made public and/or shared with ANSPs but in many cases, they are not available.

2.4.3 What does ‘taking the proper care and concern’ actually look like? It’s difficult to know when some States are disinclined to make their regulations publicly available but it seems that in many instances it simply means to operate just like a civil aircraft. When a State aircraft requests an airways clearance and complies with a controller’s clearances/instructions, it is giving the proper care and concern for the safety of civil aircraft by complying with civil aviation rules. A brief sentence from Strategic Airlift Capability (SAC) Enterprise (In 2008 ten NATO members signed together with Sweden and Finland, a Memorandum of Understanding to share the resources to acquire the maximum airlift capability for many nations in a restrictive budgetary environment) can be taken as an example: ‘fly as civil as possible and as military as operationally necessary’ (SAC 2016, p. 15).

2.4.4 Operating like a civil aircraft is not the only way in which a State aircraft can give due regard for the safety of civil aviation. In the UK and Canada, State aircraft under the control of military controllers can operate in non-segregated airspace without coordination with civil controllers. The military controllers maintain horizontal and vertical separation between the State and civil aircraft and this procedure is usually used in order to transit between segregated airspace for exercises.

2.4.5 Other States allow their State aircraft to operate in non-segregated airspace without military controllers overseeing the flight. The pilot of the State aircraft may establish their own separation from civil aircraft using on-board equipment and visual observation and the State aircraft’s route and levels may be disseminated prior to the flight. As some State aircraft are highly manoeuvrable, they may maintain a distance from civil aircraft that is much less than the separation minimum that controllers apply in the same airspace.

2.4.6 In summary, regardless of their mission, a State aircraft must always have due regard for the safety of navigation of civil aircraft and they achieve this by either:

a) operating like other civil aircraft and complying with the civil aviation rules;

b) operating inside segregated/reserved/restricted airspace; or

c) operating contrary to the civil aviation system’s rules, using special procedures established by the State that ensure the safety of navigation of civil aircraft.

2.5 State aircraft and due regard in sovereign and international airspace

2.5.1 The airspace over water beyond 12 NM from the coast, as we saw, does not belong to any State but ATS are provided according to regional agreements. Any State aircraft from any State operating in international airspace may choose to ignore the civil aviation system’s rules at any time because they are not subject to the national regulations of States that administer this airspace; however, even in international airspace, State aircraft must always operate with due regard for the safety of navigation of civil aircraft.

2.5.2 In sovereign airspace, State aircraft of the sovereign State may ignore the civil aviation system’s rules if the State’s regulations for State aircraft allow it. Remembering that the Chicago Convention resolves that ‘no State aircraft of a contracting State shall fly over the territory of another State or land thereon without authorization by special agreement or otherwise, in accordance the terms thereof’, it follows that State aircraft from a foreign State may only enter another State’s airspace and may only ignore that State’s civil aviation system’s rules if the sovereign State agrees to allow it.

2.6 Examples of regulations for due regard operations

2.6.1 The USA example

2.6.1.1 The FAA and the US Department of Defense have explicitly defined due regard as follows:

| Flight operations in accordance with the options of “due regard” or “operational” obligates the authorized state aircraft commander to:

1. Separate his/her aircraft from all other air traffic; and 2. Assure that an appropriate monitoring agency assumes responsibility for search and rescue actions; and 3. Operate under at least one of the following conditions: a. In visual meteorological conditions; or b. Within radar surveillance and radio communications of a surface radar facility; or c. Be equipped with airborne radar that is sufficient to provide separation between his/her aircraft and any other aircraft he/she may be controlling and other aircraft; or d. Operate within Class G airspace. e. An understanding between the pilot and the controller regarding the intent of the pilot and the status of the flight should be arrived at before the aircraft leaves ATC frequency. (FAA 2015, p.1-2-1) |

2.6.1.2 Moreover, the US Department of Defense has published its procedures for state aircraft operating over international waters:

| (a) DoD respects that the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) has allocated, through regional air navigation agreements, responsibility for civil air traffic management in international airspace adjacent to coastal States in specified FIRs.

(b) DoD also respects that States responsible for managing FIRs generally establish rules and procedures relating to civil aviation operations to carry out their responsibilities for providing air navigation facilities and air traffic management services in both national airspace and in assigned FIRs. However, DoD understands that these FIR rules and procedures do not apply as a matter of international law to State aircraft, including U.S. military aircraft. (1) When practical and compatible with the mission, U.S. military aircraft operating in international airspace must observe ICAO flight procedures. (2) When following ICAO flight procedures is not practical and compatible with the mission, U.S. military aircraft must operate with due regard consistent with “Operations Not Conducted Under ICAO Procedures” delineated in Enclosure 3 of this instruction. These procedures fulfil U.S. Government obligations under international law (Department of Defense 2017, p. 3) |

2.6.1.3 This makes it clear that, when in international airspace, State aircraft from the USA will comply with international civil aviation rules unless they are engaged in a mission that is incompatible with what civil aviation rules demand of them. In that case, the State aircraft may ignore controllers’ clearances/instructions. However, they must continue to operate with due regard for the safety of navigation of civil aviation.

2.6.2 The European example

2.6.2.1 In Europe, on 24th October 2013, EUROCONTROL published a set of specifications for harmonised rules applicable to IFR traffic operations not conducted under ICAO procedures, flying inside controlled airspace of the European Civil Aviation Conference (ECAC) (European Civil Aviation Conference, an intergovernmental organisation established in 1955. All EUROCONTROL member States are member of ECAC.)

2.6.2.2 The document, referred to as EUROAT (EUROCONTROL Specifications for harmonised Rules for Operational Air Traffic (OAT) under Instrument Flight Rules (IFR) inside controlled Airspace of the ECAC Area (EUROAT)), is the result of a number of years of sustained effort from EUROCONTROL and State military experts and was developed on the request of the EUROCONTROL Member States to harmonise the national rules applicable to this type of military air traffic.

2.6.2.3 While ICAO classifies the traffic only according to the type of aircraft (military, police, customs or civil) the European approach is operational, which means that the same aircraft may be served by controllers as operational air traffic (OAT) or general air traffic (GAT) as its operations require:

- General Air Traffic (GAT) means all movements of civil aircraft, as well as movements of State aircraft (including military, customs and police aircraft) when these movements are carried out in conformance with the procedures of the ICAO;

- Operational Air Traffic (OAT) means all flights, which do not comply with the provisions stated for GAT and for which rules and procedures have been specified by appropriate national authorities.

2.6.2.4 OAT is the status that facilitates military and other state aircraft flights, for which the GAT framework is not suited to provide the rules, regulations and ATM support needed to fully ensure successful mission accomplishment. This is accomplished by adhering to the three following principles (§1.3.4):

- Whenever possible the same definitions, rules and procedures as specified by ICAO (SERA) for GAT flights shall be applied;

- Required rules for OAT, in addition to and/or rules deviating from ICAO (SERA) provisions are detailed within this document; and

- Where the operational requirements of a flight are incompatible with either of the above, these requirements should be met by use of an Airspace Reservation (ARES) of appropriate type and dimension, or other methods that are considered sufficiently safe and are approved by the appropriate national authority.

2.6.2.5 Then the document, at paragraph 2.1 specifies the applicability of ICAO Rules of the Air:

| Unless the OAT rules within this document detail addition to and/or deviation from ICAO and/or SERA (Standardised European Rules of the Air: a transposition of ICAO’s rules valid for all states of European Union.) provisions, OAT-IFR flights shall be conducted in accordance with all parts of Annex 2 to the Convention on International Civil Aviation – Rules of the Air, ICAO Doc 4444 and the ICAO SUPPS – Doc 7030/4 and/or COMMISSION IMPLEMENTING REGULATION (EU) No 923/2012 (SERA). |

2.6.2.6 Moreover, paragraph 3.2 and 3.3 report:

| ATS personnel shall be trained and qualified to provide ATS to OAT-IFR flights in accordance with national regulations and should demonstrate equivalence to ESARR 5.

Air traffic control and other relevant air traffic services (ATS) shall be provided by an Air Traffic Control Officer (ATCO) to OAT-IFR in accordance with national regulations and the provisions laid down in the EUROAT. However, in accordance with relevant national regulations, States may consider personnel form other organisations than dedicated Air Traffic Services (e.g. national air defence) being appropriately qualified to provide services to OAT-IFR flights. |

2.6.2.7 EUROAT does not prevent aircraft operating with due regard if state aircraft regulation allows. Subsequently to an increase of occurrences over the high seas involving military aircraft, the European Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) has published, among others, the following recommendations:

| 1. Although the Chicago Convention does not apply to state aircraft, the Agency recommends ICAO to continue working in close coordination with the Contracting States, the relevant military authorities and organisations, and other relevant stakeholders to further update Circular 330 taking into account the results of this analysis and the work carried out in the area of civil/military coordination since its publication.

2. The Agency recommends that Member States endorse and fully apply the practices promulgated in ICAO Circular 330 and its subsequent updates 3. The Agency recommends that Member States closely coordinate to develop (if not already accomplished) and to harmonise the operational requirements and instructions for state aircraft operations in order to ensure that, when flying over the high seas, ‘due regard’ for civil aircraft is always maintained. The Agency also recommends making these procedures publicly available so that civil flight crews are aware of such procedures. 4. In addition, the Agency recommends that ICAO considers initiating amendments to Article 3 of the Chicago Convention in a way that requires Contracting States to publish their regulations or procedures in force regarding the ‘due regard’ concept for the safety of civil aircraft. 5. The Agency recommends that Member States work closely together to further develop and harmonise the concrete civil/military coordination procedures for ATM at European Union level. These coordination procedures should address, among other things, the timely dissemination of information when non-cooperative military traffic is likely to fly over the high seas within neighbouring Area Control Centers (ACCs). Similar coordination has to be implemented at the tactical level between Air Defence and ATC units when scramble aircraft becomes airborne for interceptions. 6. In cases where non-cooperative traffic over the high seas is highly probable, and where primary radar systems are still used by state/military air defence units, the Agency recommends that this primary surveillance radar data be provided to civil ATC units to the maximum possible extent (EASA 2014, p. 4). |

2.7 Developments in Guidance Material for Civil/Military Cooperation

2.7.1 ICAO, in EUR OPS BULLETIN 2015_002: Guidelines to airspace users in order to raise their awareness on State aircraft operations especially in the High Seas airspace over the Baltic Sea, reports:

| A State aircraft operating under “due regard” might not have filed a flight plan, might not necessarily establish radio communications or enable its identification through means of cooperative surveillance. State aircraft operating under “due regard” are required to maintain safe separation from civil aircraft flying in their proximity.

Civil Air Traffic Control (ATC) units have normally no responsibilities for the separation of State aircraft when they are operating under “due regard”, and can only, when known to them, provide traffic information to all other aircraft which are in the vicinity of the particular State aircraft. (ICAO 2015, p. 1) |

2.7.2 This is also what is expected from the civil pilots’ point of view. IFALPA has published a safety bulletin titled Principles and best practices in case of air Encounters, especially in the High Seas airspace commonly shared by civil & military aviation over the Baltic Sea, a reprint from the ICAO EUR OPS BULLETIN 2017_001. Air Traffic Control should consider: To share all available information of all known traffic to adjacent ATC units; When necessary, provide traffic information of non-identified traffic to all affected aircraft under control according to national rules and regulations (IFALPA 2017, p. 2)

2.7.3 ICAO, considering EASA’s recommendations, during the Fifth Meeting of the APANPIRG ATM Sub-Group (ATM SG/5) Bangkok, Thailand, 31 July – 04 August 2017, has described the status of new ICAO Document on Civil/Military Cooperation:

| An update of Circular 330 as ICAO Document 10088 Manual on Civil Military Cooperation is progressing well, with the task of completing a working draft by 4Q 2017 on track, despite the difficulties of the subject.

The new document had to strike the right balance between regional and global perspective, while keeping a readable content, and ensuring that States will agree with the guidance material contained therein. This is particularly difficult when discussing subjects such as High Seas operations. The document is being written by a group of both civil and military experts on civil/military cooperation, and will be technically overseen by the ATM Operations (ATMOPS) Panel at ICAO HQ. (ICAO 2017, p2) |

2.8 Controller actions when handling State aircraft operations

2.8.1 ANSPs should provide their controllers with guidance for handling State aircraft, including when State aircraft operate contrary to civil aviation system rules and ignore the clearances/instructions of controllers. A voluntary survey of MAs undertaken by PLC and TOC found that only around 30% of ANSPs provide their controllers with any guidance for handling State aircraft yet as demonstrated above, any State aircraft from any State may operate contrary to civil aviation rules in international airspace.

2.8.2 The absence of training and guidance may not absolve controllers from responsibility for the safety of aircraft in their area of responsibility: Appendix A to this paper suggests appropriate actions in the absence of any guidance considering duty of care.

Conclusions

3.1 Every State undertakes that when issuing regulations for their State aircraft, they will have due regard for the safety of navigation of civil aircraft. In most cases, State aircraft give due regard for the safety of navigation of civil aircraft by operating alongside civil aircraft and in accordance with civil aviation rules. When civil aviation rules are not conducive to a State aircraft’s mission, State aircraft may operate contrary to civil aviation rules but they must still have due regard for the safety of navigation of civil aircraft. State aircraft operating contrary to civil aviation rules give due regard to the safety of navigation of civil aircraft by operating in reserved airspace or using special procedures developed by the State.

3.2 Any aircraft flying over a State’s territory (its land as well as waters extending 12 NM from the coast) is subject to its sovereignty, so State aircraft may operate outside the civil aviation system if permitted by and following the relevant overflown State prescriptions. In international airspace beyond 12 NM from the coast, controllers may provide ATS but they are only administering the airspace: it is not airspace that is owned by any one State. Any aircraft operating in international airspace operates according to its national regulations and State aircraft in international airspace may operate contrary to civil aviation rules without the permission of the administering state.

3.3 Although some bodies have recommended changes to the documents and practices regarding State aircraft operations, the number of interested parties means that any change may take years to implement. In the absence of change, controllers should be trained in handling State aircraft operations. That training should include handling State aircraft that are not conforming to civil aviation rules and regulations and, where appropriate, the implications of sovereign and international airspace on State aircraft operations.

3.4 The absence of training and guidance may not absolve controllers from responsibility for the safety of aircraft in their area of responsibility. It is impossible for IFATCA to provide exhaustive guidance applicable in each State but duty of care principles may provide a starting point for controllers to consider their actions when State aircraft operate in their area of responsibility.

Recommendations

4.1 IFATCA policy is:

Controllers shall be trained in handling State aircraft operations including:

– State aircraft not conforming to civil aviation rules and regulations;

– The implications of sovereign and international airspace on State aircraft operations.

And be included in the IFATCA Technical and Professional Manual.

References

Department of Defense (2017), Use of International Airspace by U.S. Military Aircraft and for Missile Projectile Firings (DoD 4540.01), Washington DC, USA

EASA (2014), Report on Occurrences over the High Seas Involving Military Aircraft in 2014, Brussels, Belgium

FAA (2015), Order JO7110.65W, Washington DC, USA

ICAO (2001), Annex 11 to the Convention on International Civil Aviation: Air Traffic Services (13th ed.), Montréal, Canada

ICAO (2006), Convention on International Civil Aviation (Doc 7300) (9th ed.), Montréal, Canada

ICAO (2011), Civil/Military Cooperation in Air Traffic Management (Cir 330), Montréal, Canada

ICAO (2015), Guidelines to Airspace Users in order to raise their awareness on State Aircraft Operations especially in the High Seas Airspace over the Baltic Sea (EUR OPS Bulletin 2015_002), Paris, France

ICAO (2016), Procedures for Air Navigation Services: Air Traffic Management (Doc 4444) (16th ed.), Montréal, Canada

ICAO (2017), Civil/Military Cooperation Update, Presented at the Fifth Meeting of the APANPIRG ATM Sub-Group (ATM SG/5), Bangkok, Thailand

IFALPA (2017), Principles and Best Practices in case of Air Encounters, Especially in the High Seas Sirspace Commonly Shared by Civil & Military Sviation over the Baltic Sea (17SAB10), Montréal, Canada

IFATCA (2016), ATCO Duty of Care (WP/156), Presented at the 56th IFATCA Annual Conference, Toronto, Canada

SAC (2016), Compliance or Due Regard of Military Aviation Organizations with EC Basic Regulation 216/2008, Presented at the 1st Cross-Industry Safety Conference – UOA/AS, Amsterdam, Netherlands

UN (1982), United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, New York, USA

Appendix A – Controller actions and duty of care in the absence of State guidance or regulation

A.1 Not all ANSPs provide their controllers with guidance for handling State aircraft and even when they do, guidance may not envisage all types of operations. What should controllers do if they become aware of a State aircraft operating in their area of responsibility but not complying with civil aviation rules and no guidance exists?

A.2 With so many States, each with its own ATS procedures, State aircraft regulations and legal systems, it is impossible for IFATCA to develop comprehensive guidance for all controllers; however, some guidelines can be developed based on the principle of duty of care.

A.3 In its study of duty of care in 2017, IFATCA described how a duty of care is considered to exist if ‘it’s reasonably foreseeable that not performing a duty with reasonable care could result in damage to another party’ (IFATCA 2017, p. 6). The standard of care owed is measured against the rules and regulations that are provided to the controller. In situations that the rules have not considered, the standard of care that is owed is that of a reasonably competent person trained in the same profession (they need not possess the highest expert skill, just the ordinary skill of an ordinary competent man exercising a particular art) (IFATCA 2017, p. 7).

A.4 The 2017 IFATCA study proposed three questions that may be useful in determining if a controller has met the requisite standard of care. By applying those questions to State aircraft operating with due regard, we may establish some guidelines for controller action in the absence of local procedures. It cannot be emphasised enough that these questions are only offered as a tool that may be useful for controllers to measure their actions against decisions made by some courts in selected jurisdictions. They do not and cannot be an accurate reflection of the law in all the member association States.

A.4.1 Question 1: Has the controller made reasonable efforts to obtain and maintain information to ensure the safety of aircraft in their area of responsibility?

A.4.1.1 If a controller observes or is made aware of an aircraft operating in their area of responsibility that is not conforming to the rules of the airspace, the controller should make reasonable efforts to establish the intentions of that traffic. It has been established that controllers have a duty to maintain a proper lookout: for aircraft operating with due regard, this may include observing uncorrelated surveillance returns or observing unidentified aircraft out the tower windows.

A.4.1.2 Reasonable efforts to obtain and maintain information may include making blind transmissions to the aircraft on regular and emergency frequencies, informing a supervisor or contacting the authorities that are approved to operate with due regard (where communication links are established).

A.4.2 Question 2: Has the controller reasonably acted on information so as to ensure the safety of aircraft in their area of responsibility?

A.4.2.1 Having observed or been made aware of State aircraft operating with due regard in their area of responsibility, a controller should not necessarily be expected to apply separation between the State aircraft and civil aircraft. Knowing that States must, in accordance with the Chicago Convention, ‘undertake, when issuing regulations for their state aircraft, that they will have due regard for the safety of navigation of civil aircraft’ (ICAO 2006, p. 2) we can expect that there are procedures for the conduct of the State aircraft’s flight that will allow for collision avoidance. In the case of a State aircraft operating with due regard and merely transiting airspace, it may be inappropriate to attempt to provide separation; however, there may be situations where, in the reasonable controller’s opinion, the State aircraft poses a threat to the safety of civil traffic and it may be appropriate to establish some segregation. If the controller issues clearances/instructions to aircraft under their control, the controller has a duty to ensure that those clearances/instructions are accurate and not misleading.

A.4.2.2 In determining whether they will attempt to provide separation or segregation between civil aircraft operating under their control and State aircraft operating with due regard, the controller should consider that there may be dangers posed by changing the flight path of the civil aircraft. The controller may not be aware of other State aircraft operating with due regard and self-segregating from the civil aircraft’s expected flight path.

A.4.3 Question 3: Has the controller passed to the pilot information that it’s reasonable to assume the pilot will rely on to ensure the safety of their aircraft?

A.4.3.1 There is a concurrent duty on pilots and controllers to maintain the safety of a flight. Although regulations may stipulate that the pilot is responsible for the safety of their flight, courts have found that ‘the air traffic controller, whether or not required by the manuals, must warn of dangers reasonably apparent to him, but not apparent in the exercise of due care, to the pilot’ (American Airlines Inc. v United States in IFATCA 2017, p. 11).

A.4.3.2 Regardless of whether or not the controller determines that they will provide some separation or segregation between State aircraft operating with due regard, when the controller becomes aware of State aircraft operating with due regard and the controller expects that those aircraft will operate in proximity to civil aircraft, the controller has a duty to provide accurate, unambiguous and timely information to the pilot of the civil aircraft.

A.4.3.3 PANS ATM provides guidance for controller actions in the case of unknown aircraft operating in close proximity to controlled flights:

| 8.8.2.1 When an identified controlled flight is observed to be on a conflicting path with an unknown aircraft deemed to constitute a collision hazard, the pilot of the controlled flight shall, whenever practicable:

a) be informed of the unknown aircraft, and if so requested by the controlled flight or if, in the opinion of the controller, the situation warrants, a course of avoiding action should be suggested; and b) be notified when the conflict no longer exists (ICAO 2016, p. 8-21). |

A.4.3.4 PANS ATM provides similar guidance in the case of unknown aircraft operating in close proximity to uncontrolled flights:

| 8.8.2.2 When an identified IFR flight operating outside controlled airspace is observed to be on a conflicting path with another aircraft, the pilot should:

a) be informed as to the need for collision avoidance action to be initiated, and if so requested by the pilot or if, in the opinion of the controller, the situation warrants, a course of avoiding action should be suggested; and b) be notified when the conflict no longer exists (ICAO 2016, p. 8-22). |

A.4.3.5 European regulation SERA 7002 and some State regulations provide similar guidance to controllers for handling unknown aircraft operating in the vicinity of identified aircraft.

A.5 In the absence of any guidance from their ANSP, controllers may use the three questions in this Appendix to consider their actions when handling State aircraft operations. It cannot be emphasised enough that these questions are only offered as a tool that may be useful for controllers to measure their actions against decisions made by some courts in selected jurisdictions. They do not and cannot be an accurate reflection of the law in all the member association States; therefore, it is always preferable that ANSPs publish guidance for their controllers for handling State aircraft.