54TH ANNUAL CONFERENCE, Sofia, Bulgaria, 20-24 April 2015WP No. 164The Reality of Just Culture – A Roadmap for the Changing Landscape of Just CulturePresented by SESAR/EASA Coordinator |

Summary

Just Culture has been at the forefront of IFATCA’s professional and legal debates for years. This paper advocates the need to start to provide guidance material for Member Association. With the newly published EC implementation regulation on Mandatory Reporting of Occurrence in Aviation (EC 376/2014) it gives the opportunity to address some of the current ongoing initiatives in particular when establishing guidance material. The paper outlines experience from other sectors and offers a first draft of guidance for the member association.

Introduction

Definition of Just Culture

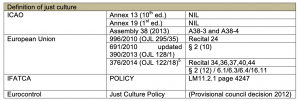

“Just Culture” is a culture in which front-line operators and others are not punished for actions, omissions or decisions taken by them, which are commensurate with their experience and training, but where gross negligence, willful violations and destructive acts are not tolerated.

1.1 What are we doing wrong?

Since more than a decade IFATCA, IFALPA, ECA and other international organizations have been advocating a concept of fair treatment of the front line operators in case of an incident and the subsequent need to report the incident without jeopardizing the professional career of the reporter.

Numerous papers were submitted to ICAO, Eurocontrol, the European Commission and the Public. The concept moved from being labeled as blame free to a just culture concept.

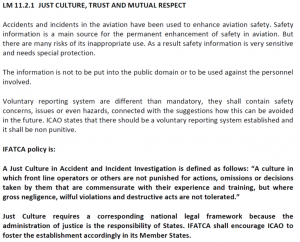

IFATCA’s definition (current policy see annex I) of just culture was introduced into the European legal system (691/2013 and 376/2014) and serves now as definition of just culture.

The need to have a protection of reporter and safety data has been confirmed in numerous resolutions and recommendation by Eurocontrol, Flight Safety Foundation, ICAO (See WP to HLSC 2015) and the European Union.

Protection of the reporter and the safety data are however limited by all the aviation safety recommendations, and legal text talking about safety protection, as a balance has to be found with the administration of justice which needs to prevent unlawful and/or criminal behaviour of the front line operators. This has been reflected in all the legal texts by some opt out clauses.

Therefore the authors of the paper came to the conclusion that we are doing something wrong. Either the system can’t be changed or the proposed changes by the aviation professionals are not fit for purpose.

The recently accepted EC Regulation on Mandatory Occurrence Reporting (376/2014) and the EC Regulation on Accident and incident prevention (996/2010) are bringing yet another level of regulatory material into the operational world which will stimulate the debate on the threads and opportunities for the front line operators.

Discussion

2.1 Aim of the paper

This Working Paper has the aim to present workable solutions for Member Associations and Guidance Material, which should be useful for all the front line workers in aviation (ATCOs, ATSEPs, Pilots and others (e.g. an aviation engineering working at a aircraft or engine manufacturer)). It is a follow up to the working paper 163 presented to Conference in 2014. This working paper is however only a start for the roadmap, which has as its aim to create usable, flexible and hands on guidance material to all the professional in aviation which will be concerned by reporting and protection of safety data as well the protection of the reporter. The legal texts and recommendation have the tendency to stop at the level of implementation and all the concerned member states of ICAO and the European Union will have to adapt their national and corporate system to the new legal requirement without having proper, workable guidance material in place. The aim of this paper is to start the roadmap which will be able to produce this implementation guidance at the corporate level, taking into account operational reality and showing the limitation of the accountability discussion.

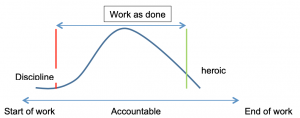

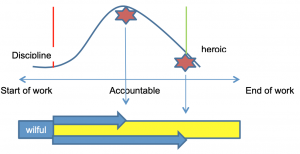

The operator is accountable from the moment he starts work till the end of work. Some of his actions might be unacceptable from a disciplinary point of view (e.g. work under influence of alcohol, showing up late etc.) and others could be qualified as heroic. Nevertheless from an accountability point of view they are all under his responsibility. The overwhelming majority of the work is however done as “work as done” and it is therefore very difficult to draw a line once an incident and/or accident happens. This is the biggest dilemma in the Just Culture discussion.

If an incident or accident happens someone will wish to draw the line if it is willful or criminal act.

2.2. Legal landscape – Just Culture

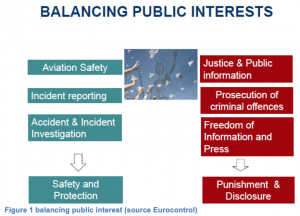

Just culture is about balancing the need for administration of Justice and Safety of the Aviation sector. This balance is a very delicate one as fundamental differences do exists between these worlds, which do not necessarily work closely with each others.

The main discussion points when talking about just culture are can be summarized as:

- What is just culture for the aviation professional;

- What is just culture for the administration of justice;

- How to encourage reporting:

- While protecting the reporter;

- While protecting the safety data.

- How to bridge the gap between the inherently contradicting interest of administration of justice and aviation safety.

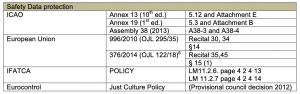

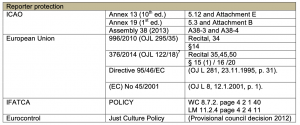

The following table serves as guidance for the reader on the current prevailing aviation recommended practices and implementation regulations on the above mentioned points. This overview has been created for the purpose of a better understanding of the issue and as reference. They can however not be converted directly into the different national laws as each of the national legal system tends to be different and tends to be set up differently when it comes to incident and accident in aviation.

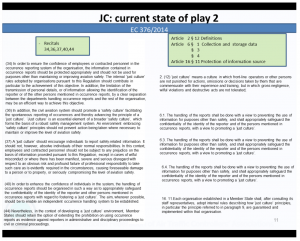

2.3. EC 376/2014 a game changer?

EC implementation regulation on the reporting, analysis and follow-up of occurrences in civil aviation will come into force on 15th of November 2015 (D. Micheaux Naudet, L. Michel, M. Baumgartner, Preventing Aircraft Accidents With Just Culture, in Air and space magazine, in print 2015).

On the 3rd of April the European Union adopted Regulation (EU) No 376/2014 of the European Parliament and of the Council on the reporting, analysis and follow-up of occurrences in civil aviation (hereinafter called Regulation 376/2014). This Regulation has been adopted by co-legislators (the European Parliament and the Council) in 1st reading following a relatively quick agreement for a text subject to the ordinary legislation procedure (Article 294 TFUE). Indeed the legislative proposal was presented by the European Commission on 18 December 2012 and an informal agreement was found between the co-legislators 12 months later, on 25 November 2013, formalized by a vote of the European Parliament on 26 February 2014 and by the Council approval on 14 March 2014. Both co-legislators strongly supported the proposal objectives and endorsed ambitious legal provisions to ensure the achievement of these objectives (644 MEPs voted in favour of the Regulation in the European Parliament – 14 against and 6 abstained – and the Council adopted it at unanimity of the Member States).

Regulation 376/2014, which will become applicable from the 15th of November 2015, creates a comprehensive legal framework across all aviation domains, aiming at preventing accidents through the reporting, analysis and follow-up of occurrences in civil aviation. In the regulation an ‘occurrence’ is defined as

“Any safety-related event which endangers or which, if not corrected or addressed, could endanger an aircraft, its occupants or any other person and includes in particular an accident or serious incident” (Article 2).

During the decision making process, the European Parliament argued that aviation professionals might be reluctant to report occurrences involving a mistake or an error they have had made but also those occurrences including a mistake or error from their colleagues. The Parliament therefore proposed to extend the principles related to the protection rules to any other person mentioned in the occurrence report. This proposal was agreed and all the provisions detailed below are therefore applicable not only to the reporter but also to any other person mentioned in the report (Recital 38 and Article 16). Furthermore, the development of new business models in the aviation industry and the increasing number of self-employed pilots led the co-legislators to ensure that not only employees but also persons whose services are contracted or used by an industry organization are equally protected (Articles 4(6) and 16(6) (7) (9)).

Regulation 376/2014 includes an essential principle, which states that employees and contracted personnel shall not be subject to prejudice on the basis of information collected through occurrence reporting systems (Recital 37 and Article 16(9)) except in cases of willful misconduct or unacceptable behavior. Would employers infringe this legal requirement, the Regulation specifies that they should face penalties (Recital 51 and Article 21).

Regulation 376/2014 establishes the principle that collected safety information collected shall be handled in such a way that it protects the confidentiality of the reporter and of other persons mentioned in the report (Recital 40 and Articles 6(1) (3) (4) and 15(1)), including through de-identification of details related to the persons involved (Recital 35 and Article 16(2)). To achieve this objective the separation between the departments handling occurrence reports and the rest of the organization is promoted encouraged (Recital 34). Moreover, the Member States and EASA are prevented from registering personal details, including name of persons, in their databases (Recital 35 and Articles 16(3) (4)).

One of the major breakthroughs of the regulation is, that it is talking about the just culture at the corporate level and current discussion among social partners in the aviation domain should foster some guidance material or negotiated applicable means of compliance for all the aviation actors being affected by this new regulation. The European Commission organizes various workshops and conferences in order to create Just culture policy at industrial level. IFATCA has been invited to join this work. In parallel the Social Partners of the European Aviation Social Dialogue are revisiting the Social charter which was signed in 2009 (IFATCA was involved in the drafting but did not sign the charter in the end).

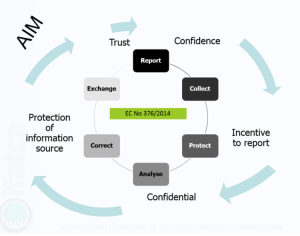

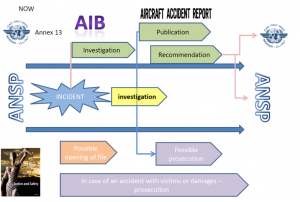

The DNA and the AIM of the EC Regulation can be best illustrated by the following graph:

Though the Regulation is a major step forward to have a just culture reporting environment there is a risk that some of the fundamentals of the balance between administration of justice and safety might be put at risk, in particular if the just culture application at the corporate level are not known to the administration of justice of the respective country.

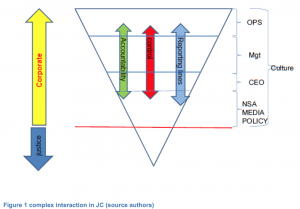

The matter being a very complex one the figure below should explain what is at risk if just culture is being solved at corporate level and challenged by the administration of justice.

The trust in a just culture reporting environment at corporate level, if the various actors are aware of the following influencing factors. Justice (depending on the national legal system) will have to intervene at any given moment and start a possible judicial actions by law. At corporate level the influences from the outside, e.g. National Supervisory Authority, Politicians, Media might force a CEO or top management to act. In such moments all the just culture policy at corporate level will be put under pressure.

Many incidents will have to be dealt with at corporate level in a just culture spirit, though this has proven in the past to be a very big challenge depending on the culture of each nation faced with an incident and or an accident.

Whereas in a case of an incident the risk to have judicial authority involved is depending on the legal framework on the bridging the gap between the administration of justice and the aviation authorities. In case of an accident the administration of justice will play a crucial role.

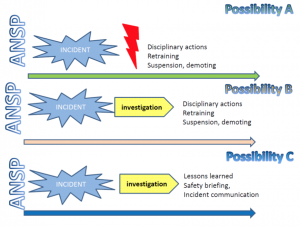

WP 163 for Conference 2014 outlines the need to look much closer at the corporate level as many of the recent examples have shown that management tries to play the role of the administration of justice via disciplinary rules and by trying to draw the line.

2.4. Experience with Just culture from an IFATCA point of view

As outlined in WP163/2014 the figures above shows the various possible reactions known after an incident in the various ANSPs. This excludes the involvement of administration of justice. All these possibilities have in the past been experienced by some of the IFATCA members and have been brought to the attention of the Executive Board for actions.

There is however a fundamental difference between just culture and the need to protect safety data, enhance reporting and protection of the reports, versus disciplinary issues, social issues and last but not least accidents.

The reality is different when we talk about social disputes and or accident compared to incidents. An accident will bring the administration of justice on the scene, whereas social issues will most probably end up in the disciplinary path and potential end up in front of a labour court.

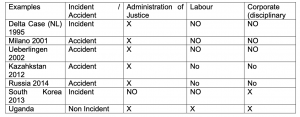

A few recent examples IFATCA had to deal with in form of table:

2.5. The experience other domains

Aviation has heralded a way forward with Just Culture. With the implementation of safety management systems both safety culture and just culture have become integral elements of the way that organisations are managed. Fundamental to the utility of an SMS is the recognition, identification of hazards and events that constitute risks to the operation. Just culture is therefore a fundamental element of an SMS, in that it is an enabler to making visible that which is unknown, but made visible through the reporting of events.

Differing domains have differing organizational and environments that IFATCA can draw upon to inform its own position, as well as different institutional arrangements within which Just culture is situated.

2.6. The Flight Deck

IFATCA works very closely with IFALPA, and in Europe with European Cockpit Association, in maintaining an understanding into how Just culture is used in the practical and messy real world. In many respects the experience of Just Culture is similar to that which ATM experiences. There are differences however.

One feature from the flight deck of particular interest is Flight Data Monitoring or FDM. For some time aircraft have flown with digital data recording facilities that have provided an invaluable source of data that is one of the principal sources of data used in incident and accident investigation. For example, the UK AAIB report of an accident to GOOBK (AAIB, 2012) illustrates the use of flight data recordings in exploring hard landings at a regional airport in the UK. Here, a trend was identified, by investigating a particular event within the scope of normal aircraft operations but triggered by an aircraft accident. The resulting exploration of the event provided new knowledge and explanations that were largely hidden until a reportable event occurred. It also demonstrates the sophisticated nature of this data. To maximize the benefits of such data, and fulfill the promise that it is believed to hold, appropriately nuanced questions need to be asked of the data and an appropriate technical capability to understand the data. How is this adjudged?

The use of this data has been widely extended to encompass normal every day aircraft operation, day in and day out. Where an aircraft operates outside defined normal operating criteria, then FDM flags this up to the aircraft operator. Another example from the serious Incident involving A320 GDJHZ, (AAIB, 2008) serves to illustrate how this can be applied and also the processes used.

How this data is used has a dimension within the scope of Just culture. For example, there can be perfectly legitimate circumstances that led to an excursion or deviation of such flight parameters. How are these acted upon or pursue? Guidelines and processes are in place, as EC regulations. Even so, there is known to be issues between the pilot and the aircraft operator in the application of FDM.

There are parallels from the use of flight data with the use of the equivalent such data in ATM. ASMT is one example, but there are more arcane systems that controllers use that provide more detailed data. Consider the use decision support tools; it is possible to develop a picture of how a controller is controlling, how they are using and interacting with the tools, the techniques that they control with by investigating the data that is recorded when the controller uses such tools. This is an area that is being discussed within ATM. It is possible to identify patterns in this data. Who decides when an observation is unacceptable, or by the use of such data when gross negligence is an issue? The power of using these types of data sources is that it is possible to explore these questions. Just culture is germane in just these circumstances.

2.6.1. The Maritime Domain

What we take for granted in aviation cannot be in the case of the maritime domain. A complicated landscape of legal positions, often developed from mercantile law, dictates roles and responsibilities of flag state and ship owner. The situation becomes further confounded when the role of the pilot and master within Port State rules. It is the master who has the accountability for the vessel. Indeed as Daniels writes:

International law has reinforced the Master’s position of supremacy in relation to the ship. The Merchant Shipping (Safety of Navigation) Regulations 200282 implement Chapter V of the International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS) 2002, giving the Master the unassailable power to use their professional judgment in the navigation of their ship, and the protection of the marine environment. Whatever instructions, for example, the charterer might deliver for proceeding to an unsafe port, the Master has the right to refuse to enter. If, of course, they do proceed, then they must give a good account of their professional judgment, and they remain Master Under God throughout, even with a pilot on board in a compulsory pilotage area. (Daniels, 2014)

The pilot has a role to in the safe navigation of the vessel. Increasingly, so does the port Vessel Traffic System, which is playing an important role when seen as a ‘total system’ and has a number of ambiguous areas within its operation (Praetorious, 2014).

The United Nations convention of the law of the sea (UNCLOS) provides the legal and institutional framework. The International Maritime Organization is an equivalent body to CAO. In Europe, the maritime equivalent to EASA is the EMSA. As Daniels (2014) opines “The ship has emerged into modern international law as a sovereign piece of territory of the Flag State.”

Reporting mechanisms exist as does the use of safety management systems and vessel data systems. Confidential reporting mechanism also exist. One indication of the state of play of reporting can be drawn from the UK’s CHIRP Maritime Advisory Board ‘safety focus in February 2015:

Judging by the reports coming to CHIRP, in 2015 the majority of ship managers will neglect to access information on hazards encountered on board their ships and actively discourage safety reports form their ships. (CHIRP, 2015)

This is only one particular view. There are other accounts that will dispute this particular view, nevertheless it is a view that may resonate with some IFATCA Mas.

Against the legal trajectory of regulation and rulemaking in the maritime domain, the criminalization of seafarers – masters and others – has been highlighted in several causalities hat have seen loss of life and public outcry. There are important lessons that ATM can learn from these. ATM Is deemed to be very safe. When an accident occurs, there can be an acute reaction to the event, as has been seen in the case of the Costa Concordia in Italy, the MV Sewol in Korea or indeed the train crash in Santiago Spain in 2013.

How would Just Culture manifest itself in any of these three examples had Just Culture had been a part of the safety landscape? Our experience shows that any aspiration that an ANSP may have of managing or controlling the events that occur subsequent to an accident where ATM is involved, is illusory. The event tales on a life of its own with an inertia that is not controllable. But, this is very different from the everyday operations that Just Culture is situated in. There are two possible modes that that Just Culture may be tested. How equipped are IFATCA MAs, or their ANSPs, for this?

2.6.2. Healthcare

Patient safety has been growing in significance in healthcare for some years. There has, as a result, been the adoption of aviation style safety interventions into healthcare. The success of these is muted. The use of checklists in operating rooms is considered as a success. The use of safety data and reporting is an area of considerable interest, but is structurally different from aviation. Vincent, Burnett, & Carthey (2013) note:

While there are lessons to be learned from other industries, many of their systems are predicated on a state of stable operations and an existing track record on safety. Translating these approaches into the NHS, with the complexity of healthcare and unpredictable demand, means that demonstrating active safety management is more challenging than for many other industries. In this environment, safety needs to be considered on a number of levels.

A fundamental tenet of the classic approach to safety, and one that Just Culture seeks to enable, is to gain knowledge of safety through reporting systems. Reporting systems were not features of healthcare until comparatively recently. In the UK NHS, Professor Vincent estimates that in excess of one million reports are filed every year. How is this volume of data made usable?

How is sense made of this data? In some cases, one being the UK NHS, leading and lagging safety performance indicators have been used. These have contributed to unexpected organisational behaviours. Dekker & Hugh identify this in events that contributed to the death of in excess of one thousand patients over several years in the Mid Staffordshire Health foundation:

What did not help was the anti-negative type of clinical governance, driven by incentives to make evidence of bad things (e.g, infections, morbidity, mortality) go away. Along the way, this may have obscured opportunities to learn and improve, and negated the reality of suffering by first victims. (Dekker & Hugh 2013)

The very thing that a just culture seeks to serve – to learn and to add knowledge – can therefore be seen to have an opposite effect with unintended consequences.

If practitioners are to disclose information, then there is an expectation that it will be used in ways that makes the system safer. The evidence is that Just culture can have unexpected consequences, and this expectation may not be upheld.

2.7. So what is Just Culture? – a reminder/reprise

What is Just Culture? It is, in one interpretation, balancing accountability with safety (Dekker, 2012) This is accountability with a small a! The right or the expectation, that an individual has to be called to give an account as much as to be called to account in a court of law or an internal company process. In so doing, the individual discloses information that can in some circumstances put that individual in professional jeopardy.

But there are many other interpretations of what Just culture means. In some instances, those with managerial responsibility interpret Just Culture as a tool or an artifact that they have responsibility for and is used in situations where safety is not a factor. It is also the case that Just culture is seen as an issue of behaviour. This manifests itself in organisations implementing codes of conduct and behaviours for operational personnel. Such moves cross into the realms of social control. How do they contribute to furthering the fundamental raison d’être of a just culture – disclosing how a system works to make it safer? The authors argue that it does not.

Just Culture is perishable. It assumes and demands trust. If managers interpret Just Culture as a tool of managerial responsibility, then the potential exists for inappropriate decisions to act, with damaging consequences: reporting rates fall, knowledge and understanding of safety in the operation becomes incomplete or impaired.

The way that safety occurrence data is used and interpreted can also influence the effectiveness of a Just Culture. If the knowledge and understanding is not acted upon, then why bother to report at all? Why should an operational controller or engineer expose themselves to microscopic scrutiny of their work by disclosure?

In many senses, the safety performance of ATM is exceptional. The human contribution to this should never be underestimated. But is there a limit to the continual improvement we have seen? Increasingly safety performance as constructed using the required taxonomies of events paints a picture of fewer events- a performance that is statistically asymptotic i.e. it will never reach zero. An event in this level of performance takes on a significance that can be greater than the nature of the event itself. It can lead to call to act or fix issues where the operational community sees no need. What to some are seen as simply a feature of day-to-day operational practice, others see as a prompt for urgent action. And this in turn will lead to the credibility or value of just culture being called into question.

The potential for this is present today in the upcoming EC regulation EC376/2014. To enact the regulation networks of experts have developed taxonomies of causal factors. The basic premise of this as presented in Clause 5 of EU No 376/2014:

Experience has shown that accidents are often preceded by safety-related incidents and deficiencies revealing the existence of safety hazards. Safety information is therefore an important resource for the detection of potential safety hazards. In addition, whilst the ability to learn from an accident is crucial, purely reactive systems have been found to be of limited use in continuing to bring forward improvements. Reactive systems should therefore be complemented by proactive systems that use other types of safety information to make effective improvements in aviation safety (EU 376/2014).

There is much to be optimistic in this clause. However, it is grounded in the classic safety paradigm, a conception of safety that is increasingly accepted is providing diminishing returns in complex social-technical systems.

In particular, the regulation aims to increase reporting. How is the success of this regulation to be measured? In terms of the frequency of unsafe events manifesting themselves after the reports have been acted upon? In terms of an increase in the frequency of reports filed?

The emphasis on reporting is skewing the way that safety is conceived. Especially with the kaleidoscope of taxonomies of casual factors that proliferate or will do so. There are known to be at least four differing schemes in existence or envisaged in aviation in 2015. Recent revelations about the nature and volume of US intelligence use of data spawned this observation:

An obsessive focus on supposedly hard technical data and big data for its own sake were key enablers of catastrophic intelligence failures at the CIA over four decades. This focus is a legacy of 1950s positivism, the naïve belief that human systems are amenable to Newtonian solutions, and that complex geopolitical situations and social movements can be understood by counting physical devices or parsing Internet log files.

IFATCA will argue that the effectiveness of such regulations should be considered in terms of the fewer reports filed the better. The salience of these reports may be very different however. But who makes sense of the data? This question is at the heart of Just Culture.

It is a feature of such systems that it is not possible to predict safe performance because such systems are intractable. That is, they are not stable in the way that linear or multi linear systems are nor is it possible to predict how the many sub-systems or components will interact, influence and behave collectively, in day to day operation. As a whole. Safety emerges as a property of the system.

The first sentence of article 5 is contradicted by the nature of intractable and complex social-technical systems. Backward, or retrospective approaches to understanding system performance, especially where they rely solely on the human as the explanatory medium, offers little to improve safety or the effectiveness of the operation. Just Culture has a part to play in gaining knowledge and understanding in how intractable systems work day in and day out in the messy world of performance variability. This is one mode of Just Culture. It is one where operational supervisors and managers are at the forefront.

Naturally, it is where this comes before the court that another mode of just culture comes to the fore.

There is evidence that increasingly more cases coming before the courts. Much has been written about the criminalization of human error. Where the perception exists that the mere inclusion of Just Culture in legislation is the conclusion of the just culture debate, the reality is that there is much more to do. There is a need to reach out to legislators and rule makers and strive to make the judiciary progressive within the way that the law is administered.

After considerable effort and work of dedicated and forward thinking Just Culture is now a part of the ATM safety landscape in many parts of the world and upheld by ICAO in Annex 19. This is a significant achievement; however, the task is not complete. The time has arrived when Just Culture needs progressive and radical developing as part of its natural evolution, as well as a natural correction or calibration of Just Culture in response to the way it was implemented, has evolved and what we have learnt.

Nevertheless, if reporting mechanisms are effective they will yield reports that contribute to Just having the reporting is not enough.

Just culture is not simple, there are no simple answers (Dekker & Nyce, 2013), but it has now evolved to an operational usage that is reduced to an abstraction that will not serve IFATCA well.

The Reality of Just Culture for IFATCA members – guidance and considerations

Making a guideline and advice on how to deal with issues concerning ‘just culture’ is very much about learning about the context in which you as a MA are situated. There are huge differences in how people look at and react upon individuals involved in incidents and accidents. In some countries there is no tolerance, legal or disciplinary, and difference between how people are treated after incidents or accidents. In other countries individual actions will only be questioned in cases where there are casualties involved. This requires MA’s to pay attention to the context in which they are situated and act accordingly. This guideline will include guidance on how to learn about your local context, as well as how to act within it. Because there are so vast differences in how people are treated there will be no clear answer to how MA’s have to react. It will be up to the people in the MA’s to take action and this guideline can only assist the MA’s in their quest for a fair and ‘just’ treatment of people involved in incidents and accidents.

3.1. Learning about local context

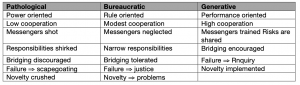

To help assist the MA’s in learning about the context they are situated, the following model of three cultures by R. Westrum (Westrum, 2004) can contribute the MA’s in understanding their local context. This model was proposed to show that information flow is both influential and also indicative of other aspects of culture; it can be used to predict how organizations or parts of them will behave when signs of trouble arise. In this case we will use it as indication for how organizations and surrounding institutions can react in the case of incidents and accidents:

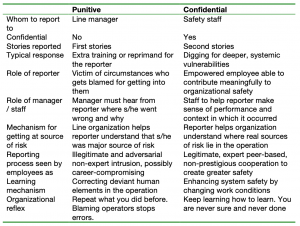

Table: how organizations process information (Westrum, 2004)

To further help MA’s to establish the kind of context in which they are situated this table from Dekker and Laursen in their study of ‘From punitive to confidential reporting’ can be of help:

Table: Results of the conversion from punitive response to confidential reporting, (Dekker and Laursen, 2007).

The table above can be summarized by polarizing between how an organization helps the reporter understand that he/she is the source of risk or the reporter helps the organization understand where sources of risk lies in the operation.

Another helpful tool to identify the context of your MA environment is how you within the organization or country talk about people who report occurrences. The list below starts with an example from a pathological organization and end with an example from a generative organization.

- Christoph (just an example of a name) reported only because he can’t get into trouble;

- The ATCO reported only because he can’t get into trouble;

- ATCOs report in cases where they will not get into trouble;

- Humans report in cases where they will not get into trouble;

- Reporting systems suffer from underreporting because people only report occurrences where they will not get into trouble underreporting is something that all reporting systems suffer from;

- Organizations shall do their best to remove institutional obstacles to reporting.

Here is a summary of the above examples and inputs to help identify your context:

Pathological level:

This is organizations or cultures that are governed by a high level of individual responsibility and often management by fear. In this kind of culture almost all incidents, even incidents with little significance, is handled by a disciplinary system and the competence of people who have been involved will be questioned. Management does this, but also fellow colleagues, who believe that there is direct connection between individual competence and being involved in incidents. Management usually handles all incidents and there are almost no safeguards in place to help operators that end up in trouble, neither by law nor on organizational level. Pathological organizations have no reporting system and do not encourage any form of information processing e.g. forums where you can exchange information about incidents and other organizational problems. There is no reporting system in place and therefore the employees are never asked to contribute to organizational improvements.

Bureaucratic level:

These organizations and cultures are where things get a little messy. Bureaucratic organizations often allow reporting systems and exchange of information, but rarely react upon it or implement any improvements based on employee inputs. These organization often have nice pamphlets where they commit to a ‘Just culture’, but reactions upon especially severe incidents is the same as in pathological organizations. These organizations usually have investigation units that take care of the analysis of incidents. But management have total control of what kind of analysis that is going to be performed, as well as what kind actions to take based on the data. Bureaucratic organizations often respond with more training, a new piece of technology to replace humans or a new procedure to make sure that people behave correct next time. There are safeguards in place to protect reporters from being punished, even on national level, but management and rule makers control them all, with little or no possibility for filing complaints from the reporting community. Unions are partially involved and asked, but have no chance to intervene and help the reporter. It is still organizations that believe that authorities have to tell the reporting community where they went wrong and what they should have done. The reporting community is spontaneously asked to contribute constructively to safety

Generative level:

A high level of trust and flow of information characterize generative organizations. People feel free to report and there is no record of people being punished for trying to do their work. In these organizations it is common to involve reporters in the investigation process and they are invited to help the organization identify where sources of risk is situated. Improving systems is about co-operation and making improvements through changing working conditions. Generative organizations know that they have to continue to invest everyday in the creation of safety – they are never sure and never done. This is achieved by open communication lines and exchange of information in an organized way e.g. continuation training and several ways to communicate with management. At the generative level processes that protect the reporter are institutionalized with involvement and authority of the employee associations. Paradoxically these processes are hardly ever used. But even in generative organizations, we (ATCOs/individuals) can’t escape to be prosecuted or legally investigated, in the wake of accidents or even in rare cases following severe incidents.

3.2. Guideline how to act within the different contexts

As suggested by Eurocontrol (Eurocontrol, 2008) and Sidney Dekker (Dekker, 2007), we will divide the guideline into three levels:

- Organizational

- National

- International

To be able to build a just culture, your own organization is the best place to start. Within your organization most of the issues that you have to deal with will emerge. It is here that the possibility for contributing to safety is best and it also within an organization the possibility to harm the relationships that build the cornerstones of just culture is most fragile. It takes little disciplinary actions from a manager or stigmatization from colleagues to tip the focus of reporting towards blame and shame. The balance between contributing to safety and responsibility/accountability is what you should pay attention to.

So what can we do?

If you are situated in a pathological organization the following might help you where to start:

At organizational level:

- Start influencing the general organizational understanding of just culture. Here you can make publications available to management and colleagues, which explains incidents as an opportunity to learn instead of blame and shame.

- Work on removing organizational disciplinary actions after an incident. Most organizations have a disciplinary regime that has rules and these rules can be negotiated. Use all means to remove the possibility of the people in power to initiate disciplinary actions.

- Try to understand how your organization protects the data that are available. Inform your members about how the data are being treated and what they should expect in case they are involved in incident.

- Advice your members on when to report and what to report. In a pathological organization it is advisable to tell as little as possible.

- Put CISM (critical incident stress management) on the organizational agenda.

- If you don’t have an investigation unit – ask for the introduction of incident investigation based on Annex13 or other international publications that can support your point of view. Here it is important to be careful, not to develop another tool for management to investigate and then blame the individual.

At national level:

- Seek communication and collaboration with authorities. They often have the goal of increased safety as you have.

- If possible make them aware of the international rules, especially Annex13 where it is specifically mentioned that incident and accident investigation is not about blame and liability.

If you are situated in a bureaucratic organization: In extension to the advice of the pathological organization the following advice might help:

At organizational level:

- Interact with management and explain the international understanding of ‘just culture’ and how people can be treated just after an incident or in the rare case of an accident.

- The interaction with supervisors and the daily operational manger level are especially important because they are the people that deal with individuals immediately after the occurrence. Ask for education and processes for supervisors and other immediate superiors.

- The disciplinary regime in your organization should not be allowed to have any influence on individual competence after ATCOs have been involved in occurrences. Work upon getting people back to work and have reinstalled without any prejudice or stigmatization. An independent CISM unit is a good tool to achieve this.

- Work upon separating investigation of occurrences to a department in your organization that has some independence from the line management. This could be the safety department but also a department within the operational department with special rights and reporting lines. It is important to note that independence within a company is almost impossible. Therefore it is about creating the best possible organizational independence possible.

- Implement processes that help you as an MA to have influence on how people are treated. This could be in form of MA participation in the body that decides on disciplinary actions. Examples of this are in place in many organizations, where one or two members of the board of the MA take active part in the organizational decision on how to react to individual competence issues after occurrences.

- Make sure you build processes to handle data. Build in safeguards that secure some control of how data are being treated within your organization.

- As a MA consider what you will do if one of your members are involved in an accident. Look for a lawyer who has experience with defending people involved in accidents in complex systems or similar. This should be done before one of your members face trouble.

At national level:

- Participate in the public debate about safety and ‘just culture’ and take contact to the legal departments in the Civil Aviation Authorities if there is one. In many countries there is little separation between authorities and the Air Navigation Service Provider, which makes it both easier but also in some cases more difficult to achieve progress. Be aware of the distinction and who to interact with.

- Set up national barriers to how the authorities can intervene with investigations and what kind of data they are allowed to use. At least ask for the separation of the investigation board and the authorities.

- Make sure that an Annex 13 investigation cannot be used as evidence to prosecute individuals.

If you are situated in a generative organization: In extension to the advice of the pathological and the bureaucratic organization the following advice might help:

At organizational level:

- Incident and accident investigation is exclusively about systemic improvements. Make sure that it stays that way and continue to discuss the difference between individual focus and systemic focus.

- As an MA make sure your ATCOs have insurance that cover costs to lawyers and salary in case they are involved in accidents or incidents that end in court. In some cases the company has insurance for all employees, but in other cases you have to cover it from some kind of individual fee.

At national level:

- Seek contact with your CAA, with the aim of building a group of ‘peers’ that can help judge performance in context for the few cases that are going to be probed for legal investigations. This is done in some countries and often avoids that cases end in courtrooms.

- Start the discussion with the prosecuting authority on how to integrate domain expertise to assist them in making judgments and how the authorities can contribute to safety.

For all three types of organizations the following can be done at international level:

- Support IFATCA and your local authorities in the implementation of safeguards for people who report.

- Participate in conferences and join the discussion on just culture.

Following these guidelines will not ensure that you have a ‘just culture’ in your organization or country. But it will help you start the process of thinking about and discussing what is a ‘just culture’. Making progress on being treated ‘just’ after being involved in an incident and accident is a process that can take years to achieve just small improvements. It is about learning and it is about keeping the process and discussion alive. Furthermore this guideline is only a sample of experience from different MAs and is by no means complete. The idea is that we as an international organization continue, to develop the guidelines and help each other to more fair and ‘just’ way, of being treated by the people who have the power to judge our work one way or the other.

Conclusion

Just Culture has been a long debate issue at IFATCA and other Aviation circles for more than two decades. Together with other international organisation IFATCA has approached Just Culture and reporting from various angles and the recent development and organisation of Prosecutor Expert Courses as well as participating to the Just Culture Roadshows with Eurocontrol together have highlighted the need to bridge the gap between the administration of justice and the aviation sector. With the publication of the EC Implementation regulation 376/2014 on Mandatory Occurrence reporting a need to create guidance material and provide assistance to Member Associations of IFATCA has been identified.

It is the aim to create guidance material which can be used by all the member association of IFATCA and not just those who are within the scope of application of the EC 376/2014. An outline of what such guidance material could look like is provided in this working paper.

As there is a natural tension between the corporate level and the administration of justice it is important to foster understanding of the just culture beyond aviation and this paper provides insight in some of the current trends in the domain of the flight deck, maritime sector and healthcare.

The guidance material for Member Association will be elaborated in the course of 2015 and will be presented to the member association together with the industrial policy which will be developed by the EC lead application work starting in March 2015.

Recommendations

It is recommended that:

- That conference accepts this paper as guidance material for inclusion and supporting guidance material;

- That conference recommend that the current IFATCA policy is reviewed and rewritten and a new policy and paper is presented at the 2016 conference on the subject of Just Culture that reflects the recent developments in Just Culture.

References

Air Accident Investigation Board (UK). (2008). Serious Incident, GDJJZ. EW/A2007/07/01. AAIB Bulletin 12/2008 AAIB: Farnborough, UK.

Air Accident Investigation Board (UK). (2012). Accident GOOBK, EW/C2012/10/01. AAIB Bulletin 5/2012. AAIB: Farnborough, UK.

CHIRP. (2015). Safety focus. Safety at sea., February 2015. CHIRP: Aldershot, UK Daniels, S. (2014). The criminalisation of the master mariner. Unpublished Ph.D. thesis.

Dekker, S.W.A., & Hugh, T.B. (2014) A just culture after mid Staffordshire. British Medical Journal Quality & Safety: Vol.23 p.356-358.

Dekker, S.W.A., & Nyce, J.M. (2013). Just culture: “evidence”, power and algorithms”. Journal of hospital administration: Vol. 2: 3.

Dekker,S.W.A. (2012). Just Culture: Balancing safety with accountability 2nd ed. Ashgate: Farnham Dekker S. (2007). Just Culture: Balancing Safety and Accountability. Ashgate.

Dekker S., Laursen T. (2007). From punitive action to confidential reporting. In Patien Safety and Health Care.

Eurocontrol. (2008). EATM, Just Culture Guidance Material for Interfacing with the Judicial System. Published by Eurocontrol.

Praetorius, G., Hollnagel, E. (2014). Control and resilience within the maritime traffic management domain. Journal of Cognitive Engineering and Decision Making. Vol.8 (4).

Vincent, C., Burnett, S., & Carthey, J. (013). The measurement and monitoring of safety. Drawing together academic evidence and practical experience to produce a framework for safety measurement and monitoring. The Health Foundation: Spotlight, London.

Westrum R. (2004). A typology of organisational cultures. In Qual Saf Health Care.

Attachment 1

Attachment 2

Last Update: October 1, 2020