54TH ANNUAL CONFERENCE, Sofia, Bulgaria, 20-24 April 2015WP No. 155Fatigue Risk Management SystemsPresented by PLC |

Summary

WP 159 Presented by PLC in Bali as well as WP 153 Presented by PLC in Gran Canaria discussed Fatigue Risk Management System (FRMS). In Gran Canaria, it was mentioned that an FRMS Taskforce, headed up by ICAO, and includes many Subject Matter Experts (SME’s), had been established with the aim to finalise policy for both Operators and Regulators in the ATC environment. This work is ongoing. The aim of this paper is to go into more detail about FRMS and to try to get some basic parts of FRMS into policy quality.

Introduction

1.1 Aviation is a 24-hour per day, 365-day-per-year industry. In most areas, ATCO’s provide service around the clock. Fatigue in ATCO’s is a risk that will never be eliminated because the hours of operation (shift work) are often not aligned with the basic sleep-wake (circadian) rhythm and need for restorative breaks.

1.2 From TPM, ATCO fatigue is defined as: A physiological state of reduced mental or physical performance capability resulting from sleep loss or extended wakefulness, circadian phase, or workload (mental and/or physical activity), affecting the subjective state that can impair an air traffic controller’s alertness and ability to perform safety related duties.

1.3 Being in a state of fatigue from lack of sleep or lack of quality of sleep can be a detriment to work and to private life. Fatigue may lead to unsafe situations due to reduced reaction times or impair the ability to perform safety related duties.

1.4 Until further guidance can be obtained from the ICAO FRMS Taskforce, this paper will provide additional information on Fatigue and Managing Risks.

Discussion

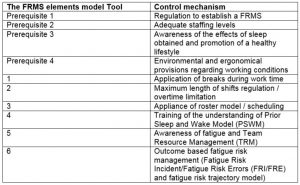

2.1 Below is the FRMS Elements Model, as contained in IFATCA TPM:

2.2 Although items 1-6 have been presented in the working papers mentioned above, a review of parts of them is necessary.

2.3 Regarding items 1-3, a summary comparing shiftwork practices stated:

“It is evident […] that a number of different shiftwork solutions are practiced. Practices vary on the different shiftwork features, such as direction of rotation (forward or backward rotating), length of shifts, individual and team rosters, days off, etc. The differences to some extent may be put down to factors such as size, culture, and legislations. (Shiftwork Study Practices, EUROCONTROL)

2.3.1 Within the same study, it was found that length of shift varied, as well as shift cycles – working days and days off, such as 4/2, 5/2, & 6/3.

2.3.2 What also could be looked at is length of time off prior to shift within a work cycle.

2.4 Item 4, Training of the understanding of Prior Sleep and Wake Model (PSWM)

2.4.1 Depending on the task measured, 20 to 25 hours of wakefulness produces performance decrements equivalent to a BAC of 0.05 – 0.10% (Fatigue Assessment: a scientific approach in the real world).

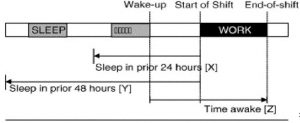

2.4.2 The algorithm (below) is comprised of three simple calculations. Prior Sleep Threshold, Prior Wake Threshold, Hazard Control Principle .

2.4.2.1 Prior Sleep Threshold

Prior to commencing work, an employee should determine whether they have obtained:

A) X hours sleep in the prior 24 hours; and

B) Y hours sleep in the prior 48 hours .

2.4.2.2 Prior Wake Threshold

Prior to commencing work and employee should determine whether the peiod form wakeup to the end of shift exceeds the amount of sleep obtained in the 48 hours prior to commencing the shift.

2.4.2.3 Hazard Control Principle

Where obtained sleep or wake does not meet the criteria above, then there is signicant inclrease in the likelhood of a fatigue-related error.

Dawson et al, Fatigue Management. 2004

2.4.3 What is then done with this information

2.4.3.1 It is a complex task to assess fatigue risk in a scientific way because fatigue is a highly subjective experience and therefore perceived in different ways entailing a variety of consequences (Dekker, 2011). In addition people have varying natures and therefore also cope with fatigue in various ways (Milanovski, 2011) (Looking back on one Year of FRAATCO: Lessons learnt from the Trial Implementation of a Fatigue Risk Assessment tool for Air Traffic COntrollers).

2.4.3.2 A critical aspect of the rules defined above is to create appropriate threshold values for the minimum sleep values for the prior 24 & 48 hours to commencing work and the amount of wakefulness that would be considered acceptable (Dawson et al, Fatigue Management. 2004).

2.4.3.3 Everyone needs about eight hours of sleep every day to be at their best. If less than eight hours of sleep is obtained, the longest periods of REM sleep, during which the mind is restored to peak performance, is missed. In addition, it should be considered that the number of ‘complete’ cycles, ie 90 minutes is a cycle, one gets each sleep period should be taken into account.

2.4.3.3.1 An example would be that I need at least 5 cycles per night to wake up feeling refreshed and rested. I should time when I go to bed backwards by 90 minute (a complete cycle) intervals from when my alarm goes off. If my alarm is to go off at 0430, I should be in bed by 2045. However, if I know I cannot get 5 complete cycles in, I should stay up until 2215, so as not to wake up mid cycle. (These times take into account approximately fifteen minutes to fall asleep)

2.5 Awareness of Fatigue and Team Resources

2.5.1 From TPM WP L004, ‘Management has the prime role for providing fatigue management and prevention of fatigue-related catastrophes.’ This does not correspond with current ideas on fatigue.

2.5.1.1 All stakeholders have to act responsibly and with care to develop mutually trusting relationships that focus on the goal of creating an organisation that effectively manages its fatigue risk. It’s a collective responsibility; no one stakeholder group can succeed alone (FRMS, EUROCONTROL).

2.5.1.2 Countermeasures of fatigue can be generally divided into measures taken by an organization (e.g. shift scheduling and rostering, rest and recovery facilities) as well as individual and team actions (e.g. making use of the countermeasures provided by the organisation, being well rested and fit for duty and watching out for each other’s fatigue levels at work).

2.5.2 Awareness of fatigue goes beyond what can be included in this paper. Awareness also leads to the understanding that it is up to the ATCO to conduct their time away from work in such a fashion as to be fit for work at their next shift. Consider that:

2.5.2.1 The National Sleep Foundation of America conducted a Poll in 2008 regarding Sleep, Performance and the Workplace. The results of the Poll demonstrated:

- 32% of all respondents admitted to driving drowsy at least once per month during the past year;

- 36% of those had nodded off or fallen asleep;

- 2% of those who drove had an accident due to driving drowsy in the past year.

What about Fatigue in the Workplace?

- 29% had fallen asleep or became very sleepy while at work;

- Only 4% left work early, and 2% did not go to work because they were too sleepy;

- YET 87% agreed that their current work schedule allowed them to get enough sleep;

- BUT only 14% had missed a social event due to sleepiness.

2.5.2.2 ATCO’s are required to maintain high vigilance and time on screen is also restricted to ensure that reduced alertness does not lead to diminished performance. Studies by scientists at IAM emphasised the importance of breaks.

2.6 Outcome based fatigue risk management (Fatigue Risk Incident/Fatigue Risk Errors (FRI/FRE) and fatigue risk trajectory model. This item has been explained in previous working papers; I see no added benefit to the ATCO to review.

Conclusions

The ICAO FRMS task force is complete and the proposed amendments were sent to the States and International Organizations for consultation on 15 December 2014 with comments to reach ICAO Headquarters by 15 March 2015. IFATCA comments have been submitted prior to conference and it is expected that the provisions will be in Final Review by the Air Navigation Commission in the spring session immediately following Conference in Sofia.

Recommendations

It recommended that this is accepted as an information paper.

References

Shiftwork Study Practices, EUROCONTROL.

Fatigue Assessment: a scientific approach in the real world.

Dawson et al, Fatigue Management. 2004.

Looking back on one Year of FRAATCO: Lessons learnt from the Trial Implementation of a Fatigue Risk Assessment tool for Air Traffic Controllers.

National Sleep Foundation.

FRMS, EUROCONTROL.

Last Update: October 1, 2020