DISCLAIMER

The draft recommendations contained herein were preliminary drafts submitted for discussion purposes only and do not constitute final determinations. They have been subject to modification, substitution, or rejection and may not reflect the adopted positions of IFATCA. For the most current version of all official policies, including the identification of any documents that have been superseded or amended, please refer to the IFATCA Technical and Professional Manual (TPM).

52ND ANNUAL CONFERENCE, Bali, Indonesia, 24-28 April 2013WP No. 161Investigate the Mechanisms for Dealing with a Critical Incident/AccidentPresented by PLC |

Summary

This paper provides an overview of current practices and assesses if they meet desired outcomes when dealing with recovery from a critical incident/accident. As the boundary between the individual and organisation can be indistinguishable in ATM, both entities will be assessed. By comparison of recovery actions from actual events, some short falls have been identified. IFATCA provides guidelines considered to be ‘best practice’ covering a broad spectrum of the impact of a critical incident/accident on ATM for both the individual and service provider.

Introduction

1.1 Whilst aviation has an enviable safety record, the continued expansion of air travel and the rapid deployment of new technologies both on the ground and in the air, it is clear the industry needs to guard against complacency. Over the last 15 years there have been major accidents and incidents that sadly have not all been as a result of human error. Yet these occurrences have had profound impact for those involved and those that operated on the periphery of the aircrew and ATCOs involved.

1.2 The subject of the paper was submitted by Italy, as it was seeking guidance material to create generic checklists of recommended practices and actions to be taken by their ATCOs following an incident or accident.

Discussion

Firstly to clearly identify the scope of this paper of ‘critical incident/accident’ and ‘critical incident stress’ (CIS) the IFATCA definition will be used.

2.1 Definition

Critical Incident/Accident is any situation faced by Air Traffic Controllers that causes them to experience unusually strong emotional reactions, which have the potential to interfere with their ability to function either at their positions or later. Critical incident stress is the reaction a person or a group has to a critical incident.

The definition clearly permits any incident affecting an individual or group to be considered. Incidents are therefore not necessarily restricted to technical issues arising from the workplace.

2.2 Case Studies

To review past performance, the following is a brief summary of some notable accidents and incidents since the year 2000 together with the actions taken and the handling of the personnel involved.

2.3.0 – 31 JAN 01: Near mid-air accident between JAL 907 and JAL958

2.3.1 Subsequent actions

The aircraft were on a collision course towards each other. The pilots of both aircraft revived conflicting instructions from their Traffic Collision Avoidance System (TCAS) and those issued by the Tokyo Area Control Centre (ACC). The pilot of JAL 907 was credited with having avoided a collision when he abruptly forced his aircraft into a dive after making a rapid visual assessment of the situation.

2.3.2 In May 2003 Tokyo police filed an investigative report concerning Hideki Hachitani, Yasuko Momii, the two controllers involved, and Makoto Watanabe, the pilot accredited with avoiding the accident, suspecting them of professional negligence. In March 2004 prosecutors indicted Hachitani and Momii for professional negligence.

2.3.3 In 2006 prosecutors asked for Hachitani, then 31, to be sentenced to one year in prison and for Momii, then 37, to be sentenced to one and one half years. On March 20, 2006 the court ruled that Hachitani and Momii were not guilty of the charge. The court stated that Hachitani could not have foreseen the accident and that the mix-up of the flight numbers did not have a causal relationship with the accident.The presiding judge said that prosecuting controllers and pilots would be “unsuitable” in this case. the Tokyo District Public Prosecutor’s Office filed an appeal with the Tokyo High Court on March 31.

2.3.4 On April 11, 2008, on appeal, a higher court overturned the decision and found Hachitani and Momii guilty. The presiding judge, Masaharu Suda, sentenced Hachitani, then 33, to confinement for one year, and Momii, then 39, for one year and six months. Both were placed on probation. Each of the two sentences was suspended for three years.

2.3.5 – 8 OCT 01: SAS Flight 686

Whilst taking off from Linate-Milpenasa airport, collided with a Cessna Citation. All those aboard both aircraft were killed together with four people on the ground.

2.3.6 Subsequent actions

On 16 April 2004, a Milan court found four persons guilty for the disaster. Airport director Vincenzo Fusco and air-traffic controller Paolo Zacchetti were both sentenced to eight years in prison; sentences of six and a half years were given to Sandro Gualano, former head of the air traffic controllers’ agency, and Francesco Federico, former head of the airport.

2.3.7 In the appeal trial (7 July 2006), Fusco and Federico were discharged. Another four people were sentenced. The pardon law issued by the Italian Parliament on 29 July 2006 reduced all convictions by three years. On 20 February 2007 the Corte di Cassazione upheld the decision of the Appeal Court.

2.3.8 – 11 SEP 01: A series of four suicide attacks involving aircraft were committed in the United States

2.3.9 The four flights involved were:

- American Airlines Flight 11 was flown into the North Tower of the World Trade Centre

- United Airlines Flight 175 was flown into the South Tower of the World Trade Centre

- American Airlines Flight 77 was flown into the Pentagon

- United Airlines Flight 93, following a struggle between the passengers and hijackers, crashed into the ground near Shanksville, Pennsylvania

2.3.10 Subsequent actions

Initially traffic in-bound to New York and Washington was refused a clearance once a pattern of the attacks became clear. After approximately 30 minutes of United Airlines Flight 175 colliding with the WTC, the FAA Operations Centre imposed a grounding of all airborne traffic regardless of destination.

2.3.11 The FAA does not have a dedicated disaster recovery plan. The FAA coordinated closely with the NATCA CISM team conduct widespread Critical Incident Stress Debriefings (CISD) for all those facilities with involvement or for those that witnessed ‘ground zero’. NATCA recognised in the aftermath how fortunate they were to have such a mature infrastructure in place with Union representatives at every facility. In some cases a phone conversation was sufficient, followed by a CISD at the affected facility. After 9/11, controllers were frequently followed by the media upon leaving the security gate at the completion of their duty. In some cases CISM team members were sent to controller’s homes. All ongoing long-term support was then generally provided by the onsite Union rep.

2.3.12 The Union leadership also provided support during an investigative process that was required. Another element, the Employee Assistance Programme (EAP) was used. This is the clinical component of the NATCA CISM to provide Mental Health Professionals on site. CISM played no role in dealing with the media, police or investigative process.

2.3.13 – 1 JUL 02: Uberlingen mid-air accident between Bashkirian Airlines Flight 2937 and DHL Flight 611

2.3.14 Subsequent actions

On 24 February 2004, Peter Nielsen, the air traffic controller on duty at the time of the accident, was stabbed to death by Vitaly Kaloyev. Kaloyev had lost his wife and two children in the accident.

2.3.15 On 19 May 2004, the official investigators found that managerial incompetence and systems failures were the main cause for the accident, so that Nielsen was surely not the only one to be blamed for the disaster.

2.3.16 A criminal investigation of Skyguide began in May 2004. On 7 August 2006, a Swiss prosecutor filed manslaughter charges against eight employees of Skyguide. The prosecutor called for prison terms of 6 to 15 months, alleging “homicide by negligence.” The verdict was announced in September 2007. Three of the four managers convicted were given suspended prison terms and the fourth was ordered to pay a fine. Another four employees of the Skyguide firm were cleared of any wrongdoing.

2.3.17 24 FEB 04: A Cessna Citation was subject to a Controlled Flight Into Terrain (CFIT) accident on approach to Cagliari-Elmas (CAG)

2.3.18 Subsequent actions

On 17 MAR 08 Cagliari court sentenced the two controllers on duty to 3 years imprisonment (reduced to 2 years due to the choice of reduced procedure) They were also required to pay 75,000 Euro in civil damages and trial expenses. The argument of the verdict was based on the authorisation provided to make a visual approach.

2.3.19 The controllers had followed the technical rules and regulations in place, both internationally (ICAO DOC 4444) and nationally (Italian AIP and AMI-Air Force ATS Manual). The courts experts also testified this.

2.3.20 The Italian Assistants and Air Traffic Controller’s Association, ANACNA, stated the lack of a conclusive and timely report by the Italian Safety Agency (ANSV) misled the judiciary in assessing the actions of the controllers against existing regulations.

2.3.21 – 29 SEP 06: In Brazil, a Mid-air collision occurred between Flight GLO1907 and business jet N600XL

Following the collision, N600XL made an emergency landing while GLO1907 crashed losing all on board.

2.3.22 Subsequent actions

In October 2006, as details surrounding the crash of Flight 1907 began to emerge, the investigation seemed to be at least partly focused on possible air traffic control errors. This led to increasing resentment by the controllers and exacerbated their already poor labour relations with their military superiors. The controllers complained about being overworked, underpaid, overstressed, and forced to work with out-dated equipment. Many have poor English skills, limiting their ability to communicate with foreign pilots, which played a role in crash of Flight 1907. In addition, the military’s complete control of the country’s aviation was criticized for its lack of public accountability.

2.3.23 Amid rising tensions, the air traffic controllers began staging a series of work actions, including slowdowns, walkouts, and even a hunger strike. This led to chaos in Brazil’s aviation industry: major delays and disruptions in domestic and international air service, stranded passengers, cancelled flights, and public demonstrations. Those who blamed various civilian and military officials for the growing crisis called for their resignation.

2.3.24 On 26 July 2007, after an even deadlier crash in Brazil of a TAM Airlines Flight which claimed the lives of 199 people, the President changed his defence minister who had been in charge of the country’s aviation infrastructure and safety since March 2006, as he was very much criticised and held responsible for problems and failures that surfaced.

2.3.25 – 23 FEB 11: A most destructive earthquake caused significant loss of life and widespread destruction of the New Zealand city of Christchurch

Oceanic control is conducted from the capital Auckland, but all other radar and procedural services for New Zealand are provided by the ACC in Christchurch.

2.3.26 Subsequent actions

Whilst the NZALPA has an active an effective CISM programme, it was not used in Christchurch for reasons that are discussed in 5.3, under the effectiveness of CISM.

Overview of Findings

3.1 From the Japanese near mid-air collision, Uberlingen and the Brazilian mid-air accident major improvements have been implemented throughout aviation to enhance procedures between aircrew and ATC governing the standardised use of TCAS Resolution Advisories (RA).

3.2 The Linate and Uberlingen accidents highlighted that aviation administrators were not immune to prosecution in relation to accidents, where poor oversight or lack of Safety Management Systems were deemed as causal factors.

3.3 An additional focus was placed on the contentious issue of Single Manned Positions an issue IFATCA has long been opposed to. Management were aware that prior to the accident, ATCOs were working alone during overnight duties. It would seem the Safety Management model of Skyguide was not effective in assessing the impact of single person operations and with hindsight this became a causal factor in the findings. Had an SMS programme been proactive, the Single Person Operation (SPO) would have been highlighted as an unsafe practice in advance.

3.4 In the Uberlingen accident, the issue of Sovereignty of airspace and legal jurisdiction was highlighted for the first time. Controllers were working for a private company, not state based and the resulting debris of the accident impacted in a neighbouring country. So it exposed those involved to two different legal systems.

3.5 Privacy protection for individuals involved in accidents/incidents was tragically played out in the murder of Peter Nielsen.

3.6 As a result of these and other incidents/accidents IFATCA has lobbied ICAO to adopt a Just Culture policy within aviation spanning all investigative processes. As a result ICAO recommendations now advise against the criminalisation and the opening of judicial procedures against pilots, air traffic controllers and other staff responsible for flight operations in the absence of negligent behaviour. However, peculiar legal issues within individual states were highlighted in both Japan and Italy. In both cases, representation was made by the President of the NTSB, IFATCA, IFALPA providing an international industry perspective on Human Factors (HF) and Just Culture grounds to no avail.

3.7 Attention to detail in R/T phraseology in these occurrences places added legal emphasis on meeting oversight and standardisation by ANSPs regarding ICAO’s Aviation English proficiency standards.

3.8 In some cases Japan and Brazil, protection of workers by ANSPs where negligence was not considered a factor was not evident or not possible within the existing National legal framework. The courts ruling on negligence was quite different.

What exists in practice to deal with accidents/ incidents?

4.1 Within the ATC environment operational staff are trained to operate in accordance within strict protocols in abnormal situations, primarily relying on checklists to ensure all avenues of assistance are employed during catastrophic events. It is in the aftermath of such events that is the focus of this paper. Many ANSPs have established a Critical Incident Stress Management (CISM) programme. This is the primary tool to assist workers involved in or impacted by any significant occurrence to be able to return to work by minimising any residual effects. These occurrences do not have to be work related. Examples may of a personal nature not job related involving traumatic marital issues or dealing with the death of a close friend.

4.2 With the terrorist attacks on the WTC, the FAA and its workforce were exposed to possibly the greatest single catastrophic series of events yet experienced in aviation. Obviously many changes were made to operational procedures to enhance security considering the extraordinary chain of events that could not have been anticipated. However, at the personnel level, CISM was employed to assist people in returning to work as effectively as possible. Considering the large scale, impact the NATCA CISM team made effective use of Critical Incident Stress Debriefings (CISD) to contend with the significant number of staff that was affected.

4.3 According to NATCA, following this wide-scale use of CISM following 9/11 assisted with unilateral support for the programme by both management and their membership. The Netherlands also has a very effective CISM programme and they responded that they do not have anything external to that programme to handle accidents or incidents.

4.4 ANACNA, now has a CISM programme that is acknowledged by its members as functioning well. They are also provided briefings each year of a preventative nature on stress recognition and proactive means to deal with it. Other changes have occurred at the National level since the last two aviation accidents. There is a clearer division of responsibility between the ASNP and the regulator. Additionally a new reporting scheme has been introduced.

4.5 There is a residual feeling amongst ANACNA members though, that changes have focussed on legal issues apportioning blame and not for the ATCOs that were correctly following an established procedure. ENAV, the Italian Service provider and the Italian Airforce have banned the use of a visual approach. The Italian regulator is now investigating implementing a new version of such a procedure.

4.6 Many ANSPs are Government or Semi-Government bodies and as such may provide anonymous counselling support for staff where CISM is not deemed sufficient. It is appropriate then to categorise what is generally available to working ATCOs. The following is compiled from research conducted on numerous MAs within IFATCA.

- ANSPs with a composite disaster recovery plan

- ANSPs providing support for CISM or similar peer support programme

- ANSP management that work closely with CISM teams, but don’t interfere in their operation

- ANSPs providing access to confidential counselling

- ANSPs providing coverage with work related illnesses. (i.e. an accident being treated as a work related illness or injury)

- ANSPs may become adversarial following an accident to protect self-interest

Is CISM and counselling enough?

5.1 The performance appraisal of the NATCA CISM teams in the aftermath of 9/11 is testament that a well administered CISM programme works. The same programme was tested during Hurricane Katrina. Some MAs though have developed disaster recovery plans. These are developed around division of responsibilities and actions for known and forecast events.

5.2 The UK is one of the few MAs known to have a composite disaster recovery plan. It was first used following the British Airways B777 crash short of the runway at Heathrow. For such a plan to work, it must come into operation as soon as the occurrence is known and cover all levels within an organisation. Not to distract from the large scale events already listed above, such an occurrence could simply be the suicide of a workmate and the resulting impact on co-workers. Hopefully this example will keep the intended coverage of such a programme to a very broad spectrum to ensure it covers all known or anticipated events.

5.3 Three major civilian disasters, Hurricane Katrina, the Christchurch earthquakes and Japanese Tsunami, although external to ATC, had direct consequences on the mental state of staff considering the events impact on basic human needs. In the earthquake situation in New Zealand, CISM was not used in such a unique occurrence where the entire workforce, plus family and friends were impacted simultaneously. Also, their CISM team was not trained to deal with major national disasters.

5.4 The NZ ANSP, Airways NZ, also has such a crisis management plan. It is a Crisis Management plan with a component of the plan being a Contingency Planning Service. Earthquakes were already a considered threat in their master plan. It was however, predicated on forecast geological evaluations done 25 years prior to the major earthquake on 23 February 11, indicating the likelihood of such an event occurring in the trans-alpine fault that runs the length of the South island and not as a localised event(s) as occurred. They were provided with some advance notice by lesser earthquakes that that caused minor damage to the city, but the major event far exceeded any predictions.

5.5 Regardless, from the recovery actions taken and the coverage and monitoring that ensued, the availability of a plan accelerated recovery and permitted a more rapid evolution of the existing plan. As part of the CISM programme the funded counsellors from the EAP were used to debrief those exposed to wide-scale event trauma (either in groups or individuals) including management, team leaders and all team members with oversight and ideas from the Emergency Crisis Management Group.

5.6 The Airways NZ CISM team is selected in-house and were not trained for major national disasters. They are usually targeted at Air Safety Incidents (ASIs) or other operational or external issues that affect personal performance. Airways NZ paid particular attention to the effects on staff based in Christchurch. If necessary, a provision of extra time off was made available at no cost, to permit staff to be with their families and to assess any individual damages they may have suffered to their property. They were also entitled to bring their families into the workplace for additional peace of mind. Showers, food and counselling were available at all times for both staff and family members.

5.7 Local managers mandated a supervisor’s session with an EAP counsellor, to assist in overcoming a ‘perception barrier’ that might have formed around what EAP was and what value it had. This resulted in more direct approaches by supervisors to their people when encouraging them to partake in the debriefings. All services provided by Airways NZ were at no cost to the staff.

Entities and areas to be considered in a composite model

- ANSP management

- Unit managers

- Supervisors

- Identify those involved directly and indirectly

- Activation of CISM

- Involvement by the staff association and or peer support

- Briefing and dissemination of information to other staff members

- Relaying of information to families and close others

- Dealing with the police or relevant authority

- Dealing the with the media

- Means to protect the identity of those involved

- Safe house checklists

6.1 ANSPs

Involvement from this level could be similar to the FAA operations centre’s capacity to make rapid decisions where there was a totally bizarre set of circumstances occurring, yet appropriate actions were taken regarding National security by grounding of all flights. From the NZ and US experiences it is instructive to consider radically unlikely events as precursors to action models. As for considering worst case scenarios, disruption and/or total failure of normal communications should be considered as a possibility. Earthquakes, tsunamis and terrorist attacks all make this a feasible occurrence.

6.2 It is inherent on the part of the ASNP to provide some sort of programme to cater for the integration of workers exposed to either a small scale incident involving quite a limited number of employees, then scaling up to much broader scales where there is a widespread impact.

6.3 Provide an integral link with Government, Military, Airport Authorities, Airline Operators, medical facilities as events dictate.

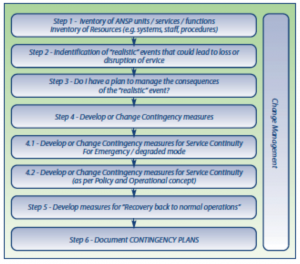

6.4 Eurocontrol produced Guidelines in Contingency Planning in 2009 . It is an exhaustive document detailing the steps to consider to formulate such plans. In their model it is suggested that once a composite plan has been developed, that realistic scenarios be fed through the model to validate suitability.

6.5 Unit Managers

Consider the consequences of natural disasters, fire and terrorist threats on their facilities and take appropriate actions. Possibly consider a ‘lock down’ of the facility. Provide assistance with manning, provision of briefings to operational personal and placing some means of additional oversight of operations to minimise the reporting workload of supervisory staff.

6.6 Supervisors

Record those involved and directly involved. Quick access to Association/Staff/ peer support groups for the activation of CISM if necessary. Consider the privacy of the individuals involved in a possibly traumatic event, ensure they can be removed from the workplace to an isolated area.

6.7 CISM/Peer Support

The Federation endorses the use of professionally trained peers in the provision of critical incident stress management (CISM) to colleagues experiencing critical incident stress. Any conversations or discussions of events at this level are deemed totally private and not to be seen as part of the investigative process. A part of the success of CISM is predicated on those involved being able to express their recall of events in a secure environment.

6.8 In events where technical infringements have occurred or suspected to have occurred, IFATCA has established policy for actions taken in the event of an incident/accident. It would be best administered at the peer to peer level to initiate this process and ensure that it is adhered to, to moderate any unnecessary stress on the individual or individuals concerned. If the case warrants the use of dedicated

6.9 The areas covered by policy vare as follows:

- Just culture and its application

- Exemption from duty

- Right of representation

- Protection of identity

- Use of recorded data

6.10 Peer support should also monitor as far as possible the personal conduct of those involved with regard to stress management.

6.11 Dealing with the media

The media in general may purport ethical behaviour, but in general their aim is to sensationalise events for commercial gain. If ATM is seen by the public to be secretive in nature by not providing details to the media, it can be counter- productive. The Eurocontrol study of the media made the following determination:

“The low profile of air traffic control in forming opinion among the general public could be storing up problems for the future in a world where transparency and reporting are increasingly becoming the standard practice required of social actors. What legitimacy will the technological and organisational choices made in the future by ATC have in the eyes of the general public if their knowledge of the field is sketchy or non-existent?”

6.12 The report also formed a link between the political orientations of the newspaper. The political leanings of the paper also seem to be a major factor in apportioning blame. Left- wing publications tend to highlight the failure of the system and tend not to concentrate on the individual. Right-wing establishments, while not denying the system is to blame, systematically highlight the human failings of those involved.

6.13 It was established that five parameters trigger and sustain media interest in ATC:

- The scale of the accident and how dramatic it is

- The cumulative effect. Is it serial in nature indicating a flawed system?

- The local dimension. How close was the event to the organisation reporting it?

- The presence of specialised journalists in the editorial team

- The involvement of the judiciary. The press tends to feed off a trend where a judiciary demonstrates an impetus to proceed quickly from finding causes to apportioning blame and responsibility

6.14 The report also determined that the handling of the Milan and Uberlingen cases demonstrated a shift in ideology when accepting levels of risk in a system. Risk is inherent in every facet of life and until recently it was an accepted norm that new technologies brought with them added risks in their evolution to maturity. The reporting of recent cases though has indicated a reluctance to accept such a stance.

6.15 Obviously dealing with the media is an art form and is usually strictly controlled by the senior management of ANSPs. Staff associations are commonly solicited for comment, however the advent of social media has further complicated the issue of rapid dissemination of information, be it factual or otherwise. It appears the best result comes from striking a relationship with the media and permitting a better understanding of the ATM environment prior to events occurring. Attempting to add technology and human factors after the event can always be seen as a ‘cover up’, sparking a lack of trust.

6.16 Social Media

Regarding the use of Social Media, management and staff associations should conduct an education programme highlighting the adverse side effects of transmitting potentially damaging information without any form of control. The tragic murder of Peter Nielsen should provide ample demonstration of the consequences of such actions.

Conclusions

7.1 The evidence from US experiences would indicate that a plan for recovery actions is not a necessity. However, to ensure a complete coverage of all aspects and entities is covered within the events included within the scope of this paper, it is plausible to argue that a plan linking staff and management at all levels with a flexible action plan is more prudent. The plan should be readily adaptable to the circumstances as aviation history attests forecast predictions are rarely accurate. A very instructive example: who would believe that a jet aircraft could suffer a double engine flame-out shortly after departure and land in the Hudson River, clearing numerous bridges and river traffic, without loss of life. Yet who would have conceived a disaster plan with such an outcome?

7.2 So several cases here indicate that a plan is better than no plan. While the basis of the NZ Crisis Management Plan may have been totally inadequate where forecast contingencies were not accurate, it still provided a solid basis for a rolling action plan. As is evident in Threat and Error Models (TEM), human performance is always demonstrated to be far more reliable under pressure, if some sort of rehearsal of imagined events is undertaken prior to an occurrence. The strategy of any plan should include the division of responsibilities for actions taken to avoid duplication of effort or omission.

7.3 There is sufficient evidence from the experience gained from the incidents/accidents detailed above that contingency planning at the minimum should cover actions by the following entities and action items.

7.4 Entities

- ANSP management

- Unit managers

- Supervisors

- Staff Association

- CISM team activation

- The individual or individuals concerned

- EAP

7.5 Action items

- Ensure those directly and indirectly involved are identified and recorded for comprehensive coverage by CISM/EAP

- Involvement by the staff association and or peer support

- Activation of CISM

- Briefing and dissemination of information to other staff members

- Relaying of information to families and close others

- Dealing with the police or relevant authority

- Dealing with the media

- Means to protect the identity of those involved

- Use of events to update existing plans and re-educate EAP and CISM staff.

- Safe-house check-lists

7.6 CISM has been the core component evident in all the incidents/accidents listed above with the exception of the NZ earthquakes. This coming from the unique occurrence impacting all ATM staff in Christchurch simultaneously and members were not trained. Considering the importance and demonstrated effectiveness of CISM in other cases, it should provide ample grounds for those ASNPs that currently do not have a programme to initiate one as soon as possible. For those that do have a CISM programme, it is also vital in line with US experience, to constantly undertake reviews of procedure, analyse the actions taken in past events and upgrading of the skills where necessary for CISM peers.

7.7 For those MAs that don’t fall into the above categories because of a reluctant ANSP, an in-house peer to peer support model using the coverage specified above is still advantageous for the same reasons for having a sanctioned plan in lieu of no plan.

7.8 If CISM is being considered Eurocontrol have an all-inclusive generic introduction plan; Critical Incident Stress Management User Implementationvii

7.9 For the individuals concerned, Appendix 1 is a generic check list of suggested actions. Not all MAs may have access to legal representation or the political environment to ensure their rights are preserved. For this reason the suggested course of action will need to be tailored to match the circumstances.

Recommendations

IFATCA recommends MAs work with their respective ANSPs to formulate action plans for both individuals and providers along suggested guidelines or modifies existing plans if they are assessed as not suitable.

References

IFATCA Technical and Professional Manual.

Accident Investigation Into A Near Mid Collision. Hiroaki TOMITA (Investigator General ARIC Japan).

https://asasi.org/papers/2005/Hiroaki%20Tomita%20%20near%20collision%20in%20Japan.pdf

EUROCONTROL Guidelines for Contingency Planning of Air Navigation Services.

IFATCA Technical and Professional Manual, 4 4 2 1. Accident and Investigation.

Safety of Air Traffic as seen by the press. Eurocontrol Experi\ental Centre study report. EEC/SEE/2005/2007.

Eurocontrol: Critical Incident Stress Management User Implementation Guidelines.

https://www.skybrary.aero/bookshelf/books/951.pdf

Appendix 1 – Action Plans for Individuals

General advice:

- Have yourself relieved from your position immediately.

- Immediately contact your association representative.

- Decline to make any statements to anybody, written or oral.

- Make personal notes of the incident, but do not make them public.

- With the assistance of your Association nominee, complete and submit safety incident report. Only fill in the facts pertaining to your actions in time sequence.

- Seek legal opinion to protect your Rights.

- If you are given a direct order by your supervisor to make a statement, then only outline the facts: name, address, control position, time, etc.

- Avoid a detailed statement at this time as a written statement should be perused by your legal representative before submission to your supervisor.

- Before issuing a statement insist on a review of all audio, radar, CCTV or recorded information.

- Under no circumstances should you agree to a joint ATS/Safety Board or Regulator interview. You should insist that separate Safety Board/Regulator and ATS interviews take place.

- Contact the CISM team if provided.

- Make no official statements without witnesses (Association representative, Supervisor, CISM or legal representative).

“It is within your interests to follow these procedures, particularly in relation to statements. Remember failure to do so could prejudice your future”

Action plan coverage for ANSPs

Due to radically different scales of manpower, territorial coverage and political environments of MAs, in order to be effective, IFATCA believes the following areas of coverage should be addressed according to location specific issues.

- ANSP management

- Unit managers

- Supervisors

- Identify those involved directly and indirectly

- Activation of CISM

- Involvement by the staff association and or peer support

- Briefing and dissemination of information to other staff members

- Relaying of information to families and close others

- Dealing with the police or relevant authority

- Dealing the with the media

- Means to protect the identity of those involved

- Safe house checklists