DISCLAIMER

The draft recommendations contained herein were preliminary drafts submitted for discussion purposes only and do not constitute final determinations. They have been subject to modification, substitution, or rejection and may not reflect the adopted positions of IFATCA. For the most current version of all official policies, including the identification of any documents that have been superseded or amended, please refer to the IFATCA Technical and Professional Manual (TPM).

48TH ANNUAL CONFERENCE, Dubrovnik, Croatia, 20-24 April 2009WP No. 88Aerodrome – Review ICAO Manual on the Prevention of Runway IncursionsPresented by TOC |

Summary

In 2001 ICAO took action to address the problem of runway incursions. Seminars were held in several regions and ICAO has done a considerable amount of work to improve runway safety and to decrease the number of runway incursions. This includes the publication of ICAO Doc 9870 Manual on the Prevention of Runway Incursions. TOC has reviewed this ICAO Document on issues relevant to Air Traffic control (ATC) and aims at providing guidance to the Member Associations (MAs) when implementing recommendations from this Manual into ATC operations. This paper recommends amending IFATCA Policy on stop bars.

Introduction

1.1 Recently, the urgent problem of runway incursions, which reached a climax between 1995 and 2005, came again to the attention of the States, aviation international organisations and ICAO. Canada conducted an extensive campaign of studies between 1996 and 1999, EUROCONTROL and ICAO launched important prevention programs. In 2007, ICAO published the first edition of Doc 9870 Manual on the Prevention of Runway Incursions. Several critical areas were identified that needed to be investigated and which had a relation to overall runway safety, including radiotelephony phraseology, language proficiency, equipment, aerodrome lighting and markings, aerodrome charts, operational aspects, situational awareness and Human Factors (HF).

1.2 The objective of ICAO Doc 9870 Manual on the Prevention of Runway Incursions, containing runway incursion prevention guidelines, is to help States, international organizations, aerodrome operators, Air Traffic Service Providers (ATSPs) and Aircraft Operators (AOs) to implement runway safety programmes.

1.3 At Istanbul 2007 Conference, Committee B felt the need to review ICAO Doc 9870 Manual on the Prevention of Runway Incursions, in order to identify points for improvement, and to check whether IFATCA Policies are in line with the content of the Manual or that changes/additions are required. The Technical and Operations Committee (TOC) was tasked accordingly to review ICAO Doc 9870 Manual on the Prevention of Runway Incursions for the IFATCA Conference 2008 in Arusha. However, the professional aspects in ICAO Doc 9870 Manual on the Prevention of Runway Incursions needed to be reviewed as well. Therefore, the review for the IFATCA Conference in 2008 remained only at a high level and the intention was to review it more extensively together with PLC for the 2009 Conference. The objective was to identify possible points for improvement, which would be submitted to ICAO at the moment that this would be asked. Besides this, the second objective was to provide MAs with guidance to use the recommendations in the ICAO Doc 9870 Manual on the Prevention of Runway Incursions in a proper and safe way.

1.4 If reference is made to ‘the Manual’ or ‘the ICAO Manual’ in this paper, then this refers to ICAO Doc 9870 Manual on the Prevention of Runway Incursions.

Discussion

2.1 The glossary of the Manual contains a number of terms that are essential for runway safety, however not all these terms have yet been included within the Annexes of Procedures for Air Navigation Services (PANS) and Standard and Recommended Practices (SARPs).

Therefore these terms are defined in the glossary:

- Hot spot

- Runway incursion

- Just culture

- Runway incursion severity classification (RISC) calculator

- Local runway safety teams

- Sterile flight deck

2.1.1 According to the ICAO Manual “just culture” is:

“An atmosphere of trust in which people are encouraged (even rewarded) for providing essential safety-related information, but in which they are also clear about where the line must be drawn between acceptable and unacceptable behaviour (definitions “not yet included in Annexes or PANS documents” – Glossary, page vii).

“Just culture philosophy is designed to counter the strong natural inclination to blame individuals for errors that contribute to runway incursions. A key objective of the just culture perspective is to provide fair treatment for people, applying sanctions only where errors are considered to be intentional, reckless or negligent”.

The use of just culture in occurrence reporting was strongly advocated by the Eleventh Air Navigation Conference (AN-Conf/11)” (para 5.2).

IFATCA policy is:

| “A Just Culture in Accident and Incident Investigation is defined as follows: A culture in which front line operators or others are not punished for actions, omissions or decisions taken by them that are commensurate with their experience and training, but where gross negligence, willful violations and destructive acts are not tolerated.” |

The ICAO definition in this Manual is not yet endorsed by higher level documents, but it is also considered not strong enough to guarantee the liability of front line operators. Consequently, the IFATCA policy on the matter is still valid.

2.1.2 The introduction starts with a definition of a runway incursion according to ICAO Doc 4444 PANS-ATM:

“Any occurrence at an aerodrome involving the incorrect presence of an aircraft, vehicle or person on the protected area of a surface designated for the landing and take-off of aircraft.”

In the introduction the Manual refers to the report of Transport Canada which mentions a number of issues likely to be responsible for the continuing increase in runway incursions. These issues include the increase of traffic volume, capacity-enhancing procedures, inadequate aerodrome design and increasing environmental pressure that require too many configuration changes. The mentioned issues, combined with inadequate training, poor infrastructure and system design and inadequate ATC facilities can lead to an increased risk of runway incursions.

2.1.3 Chapter one further explains the purpose and contents of the Manual and also stresses the need for aviation safety programmes that have a common goal – to reduce hazards and mitigate and manage residual risk in air transportation. It is explained that the Manual aims primarily to provide guidance essential for the implementation of national or local runway safety programs, although foreign object debris and animals straying onto the runway are recognized as issues concerning runway safety.

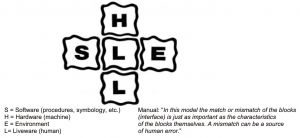

2.2 Chapter two addresses information on the “Contributory factors” that can lead to a runway incursion. The chapter starts with some background information about parties, like controllers, pilots and drivers, who can be involved in a runway incursion. Furthermore it is explained how the SHEL model can be used for the analysis of a runway incursion.

Figure 2.1 The SHEL Model

The Manual stresses:

“Importantly, the SHEL Model does not draw attention to the different components in isolation, but to the interface between the human elements and the other factors. The contributory factors described in this chapter (normally designated as Liveware by the SHEL Model) do not exclude contributions from other aspects of organizational life (e.g. policies, procedures, environment) which are critical factors associated with safety management systems and must be addressed to improve safety overall”.

Under the title ‘contributory factors’, only those representing “human active failures” are taken into account. This appears unfair and important to note for IFATCA, since it drives readers’ attention to only one field of the model, relieving analysis and investigation efforts from other fields. ICAO’s argument in the text is the reason why IFATCA proposes to use the SHEL Model in a different way, so that all fields are investigated in depth.

The application of the SHELL Model (Frank Hawkins, 1984 – Also see IFATCA Technical and Professional Manual, WP 172/2004) by ICAO in the Manual would improve the quality of the recommendations greatly.

This model provides the following more extensive explanations:

S = Software (laws, rules, regulations, procedures, charts, AIPs, etc.);

H = Hardware (infrastructures, equipments, etc.);

E = Environment (climatology, physical, anthropic, operational, etc.);

L = Liveware (decision makers, line managers, designers, operational and staff, personnel, etc.) as one of the element of the system;

L = Liveware again, not as one of the 4 fields of the Model, but as its “core”, strength and weakness, interfacing all other fields and around which the (airport, aviation, Air Traffic Control (ATC)) system must be shaped, in order to enhance the positive impact of the human factors and reduce the negative one.

Especially the occurrence analysis would benefit if the SHELL Model would be applied in stead of the SHEL model.

2.2.1 The Manual lists possible scenarios that can be identified as runway incursions:

a) an aircraft or vehicle crossing in front of a landing aircraft;

b) an aircraft or vehicle crossing in front of an aircraft taking off;

c) an aircraft or vehicle crossing the runway-holding position marking;

d) an aircraft or vehicle unsure of its position and inadvertently entering an active runway;

e) a breakdown in communications leading to failure to follow an air traffic control instruction;

f) an aircraft passing behind an aircraft or vehicle that has not vacated the runway.

The Manual mentions statistics that show that most runway incursions occur in visual meteorological conditions during daylight hours; however, most of the runway incursions resulting in accidents occur in low visibility or at night.

2.2.2 Several recurring scenarios of the list in 2.2.1 are included as explanation.

Some of the scenarios appear not completely to reflect the ICAO definition, i.e.:

- Letters a) and b) relate the incursion to the presence of a vehicle or second aircraft operating on the runway. This appears not to be in line with the definition that doesn’t require a “conflict” to characterise a runway incursion.

- Letter c) is a general circumstance, that may include a) and b), but doesn’t qualify the crossing as “incorrect”. The “incorrect” qualification is necessary to characterise a runway holding position crossing as runway incursion.

- Letter e) doesn’t relate the failure to an incursion.

- Letter f) describes a scenario commonly resulting from a correct ATC instruction, correctly complied by an aircraft, with the objective of expedite traffic.

Only letter d), actually, reflects a RI definition, describing the occurrence and its cause. A list of scenarios may be useful for analysis. Therefore proposes the following, according to the definition and to the most common hazard identification methodologies, as a list of scenarios related to possible hazards:

a) aircraft incorrectly crossing a runway holding position, for entering or crossing a runway;

b) aircraft landing on, or taking-off from, an incorrect runway, or attempting such manoeuvres;

c) vehicle or pedestrian incorrectly crossing a runway holding position, a road holding position protecting a runway or the boundary of the runway protected area;

d) aircraft, vehicle or pedestrian unsure of own position and inadvertently entering a runway protected area.

Scenarios a), b) and c) may occur following an active failure involving ATC, the user of ATC service (pilot, driver or pedestrian) or both. Scenario d) mainly refers to active failure not involving ATC. In accordance with the Manual, all runway incursions should be reported and analysed, whether or not another aircraft or vehicle is present at the time of the occurrence, with the objective of identifying latent causes behind the active ones and recommend remedial actions to remove as many hazards are possible and mitigate the residual risk.

2.2.3 Communication could be an essential contributing factor, a breakdown in communication is also a common factor in runway incursions. The Manual addresses several scenarios which will lead to a breakdown in communication and can result in a runway incursion. Although the Manual starts with mentioning that it is mainly addressing “Liveware” issues it also addresses several procedure (Software) issues. The manual does not mention essential hardware issues related to communication failures.

2.2.4 In its current edition the Manual mainly focuses on a large number of communication and operator (ATCO, pilot and vehicle driver) contributory factors that usually only represent the active failures leading to runway incursions. Chapter 2 could be enriched, and constitute a more powerful tool for States and aviation organisations, by including all the relevant factors listed in accordance with the SHELL Model, with greater attention to latent failures.

The text in Appendix A of this working paper is attached with the objective of being used as an input to ICAO in case a next version of the Manual is produced. Besides this, it can also be used for an awareness campaign by the IFATCA Global Airport Domain Team (GADT). Finally, it can also be used by MAs in addition to the Manual, providing a more comprehensive list of relevant contributory factors.

2.3 The title of chapter three is “Prevention Programme”. The Manual stresses the need for the establishment of a local Runway Safety Team (RST). The primary role of this team should be to “develop an action plan for runway safety, advise the appropriate management on the potential runway incursion issues and to recommend strategies for hazard removal and mitigation of the residual risk. These strategies may be developed based on local occurrences or combined with information collected elsewhere”.

2.3.1 ICAO advises that RST should comprise of representatives from aerodrome operations, air traffic service providers, airlines or aircraft operators, pilot and air traffic controller associations and any other groups with a direct involvement in runway operations.

2.3.2 Next in this chapter ICAO mentions ‘Objectives’:

“Once the overall number, type and severity of runway incursions have been determined, the team should establish goals that will improve safety of runway operations.”

The objective for a RST should be generally valid for all controlled airports, and not only at airports with a considerable number of reported runway incursions. According to ICAO, the objective of the RST is to establish goals to improve the safety of runway operations.

ICAO mentions several examples of possible goals:

“a) to improve runway safety data collection, analysis and dissemination;

b) to check that signage and markings are ICAO compliant and visible to pilots and drivers;

c) to develop initiatives for improving the standard of communications;

d) to identify potential new technologies that may reduce the possibility of a runway incursion;

e) to ensure that procedures are compliant with ICAO Standards and Recommended Practices (SARPs); and

f) to initiate local awareness by developing and distributing runway safety education and training material to controllers, pilots and personnel driving vehicles on the aerodrome.”

These are excellent goals that should be listed within the Manual according to the SHELL Model. TOC has produced a list of goals for consideration, which is attached in the Appendix A of this paper. It should be clear that the RST itself cannot have any operational or administrative duties, in order to maintain a “third party” status against operators and service providers. The team only perform analysis, provide recommendations, verify implementation and advise the appropriate management.

2.3.3 The Manual suggests generic terms of reference for a RST to assist in enhancing runway safety. Additional requirements for a RST are listed in the Appendix A of this paper.

2.3.4 The Manual provides extensive guidance for the identification and suitable mitigation strategies for Hot Spots. Furthermore the Manual explains how plans for “action items” can be developed, the Manual lists how responsibility should be delegated regarding tasks associated with action items and how the effectiveness of completed items should be assessed. At least equally as important are the directives for States to find education and awareness material such as newsletters, posters, stickers and other educational information which are invaluable tools to reduce the risk of runway incursions from the liveware side.

2.3.5 It is very satisfactory for IFATCA that ICAO stresses in para 3.4.3 ( ]Hot spot) the importance to remove the hazard and mitigate the risk when a HOT SPOT has been identified.

2.3.6 Chapter 3 gives excellent guidance how to establish a RST, but omits to provide direct guidance for establishing a “Runway Incursion Prevention Programme” as the title of the chapter would assume.

2.4 Chapter 4 (Recommendations for the prevention of Runway Incursions) stresses that:

“these recommendations will enhance the safety of runway operations through the consistent and uniform application of existing ICAO provisions, leading to predictability and greater situational awareness”.

2.4.1 Not all the recommendations in Chapter 4 will generally enhance runway safety due to the diversity of aerodromes and aerodrome operations worldwide. Some of the recommendations can enhance runway safety at one aerodrome but at the same time can also be decreasing the level of safety at another aerodrome. It should be at the interpretation of the decision making management, and thereby advised by the local RST, to decide which of the recommendations can be used to improve the level of safety at the local aerodrome. The aim is to improve runway safety and situational awareness, this goal can be achieved by many different measures.

2.4.2 Regarding communications, the Manual advises to use full call-signs for runway operations and to use standard ICAO phraseology and communication procedures, and according language requirements. Furthermore ICAO stresses the importance for read- backs in runway operations. According to the Manual, all communications associated with the operation of each runway (vehicles, crossing aircraft, tows, etc.) should be conducted on the same frequency as utilized for the take-off and landing of aircraft. This recommendation may introduce increased risks in relation to the hazard of miscommunication due to existing language barriers, this also based on experiences reported by operational controllers. The real objective is to enhance situational awareness of all runway users by suitable means, after which the “all users on same frequency” and “active Situational Awareness by dedicated traffic information” could be mentioned as non exhaustive examples. In fact, where English is not the native language, the increased risk related to miscommunication may decrease situational awareness, rather than to enhance it. Consequently, the objective must be pursued in different ways, depending on local situation, and left to local RST for consideration. Alternative procedures might be acceptable as a temporary solution, but the ultimate effort should be to establish a global aviation environment where all participants reach their required language level of English, and where all communications associated with the operation of each runway can be conducted without the risk of miscommunication on the same frequency.

2.4.3 The Manual recommends aircraft operators to train pilots on aerodrome signage, markings and lighting. Aircraft operators are advised to adopt the concept of a sterile flight deck during taxing and to implement the requirement for an explicit clearance for crossing a runway within the flight deck procedures. Furthermore best practices for pilots’ planning of ground operations should be promoted by the aircraft operator. Some of these recommendations sound more a Regulators’ responsibility, rather than that these should be left to individual aircraft operators’ good will.

2.4.4 According to the Manual in para 4.4:

“Pilots should never cross an illuminated stop bar at red when lining up on, or crossing, a runway unless contingency procedures are in use that specifically allow this”.

And in para 4.5.4:

“Stop bars should be switched on to indicate that all traffic shall stop and switched off to indicate that traffic may proceed”.

The following para 4.5.5:

“Aircraft or vehicles should never be instructed to cross illuminated red stop bars when entering or crossing a runway”.

The Manual also mentions, as an example of a contingency measure, the use of follow-me vehicles.

IFATCA Policy is:

| “No procedures should be introduced that require the crossing of a stop bar at red.” |

This implies that, in IFATCA’s view, airport configuration and stop-bar systems should be designed in order to always provide an alternative solution, such as alternative taxiways served by independent stop-bar systems. This may currently be impossible at many airports, but should constitute an objective for IFATCA and MAs. Furthermore current IFATCA Policy could imply that it should be allowed to cross a stop bar at red when the procedure already exists and only applies to newly introduced procedures.

Other ICAO documents like ICAO Annex 2 Rules of the Air state, 3.2.2.7.3:

“An aircraft taxiing on the manoeuvring area shall stop and hold at all lighted stop bars and may proceed further when the lights are switched off”.

ICAO Annex 14 Aerodromes contains information on stop bars on a detailed level, but does not contain any procedures on the crossing of a stop bar.

ICAO Doc 4444 PANS-ATM 7.15.7 states:

“Stop bars shall be switched on to indicate that all traffic shall stop and switched off to indicate that traffic may proceed.”

Doc 9476 Manual of Surface Movement Guidance and Control Systems (SMGCS) Appendix A, 2.4:

“The lights are operated by air traffic control to indicate when an aircraft should stop and when it should proceed.”

The discrepancies within the ICAO Documents need to be addressed, especially the use of the words “shall” or “should” needs to be consistent and confined to “shall” to stress the obligation. Stop bar contingency procedures should also be addressed by ICAO, as they are currently not.

2.4.4.1 Paragraph 4.4 in the Manual mentions that pilots should:

”a) not accept an ATC clearance that would require them to enter or cross a runway from an obliquely angled taxiway.

b) Contact ATC “if lined up on the runway and held more than 90 seconds beyond anticipated departure time”, “if there is any doubt” about a clearance/instruction or about “their exact position” at the airport.

c) turn on aircraft landing lights when take-off or landing clearance is received, and when on approach” and “turn on strobes when crossing a runway.

d) maintain “heads up” for a continuous watch.”

Recommendation a) addresses a very critical issue; the Paris (May 2000, a MD-83 and a Shorts-360 collided on a runway at Charles de Gaulle Airport) accident and Munich (May 2004, a B737-300 missed an ATR-42 by a few metres. The ATR had lined up without ATC approval) incident, as results of runway incursions have shown that the risk associated with the use of obliquely angled taxiway is very high. These two occurrences have led to recommendations within the European Action Plan for Prevention of Runway Incursions (EAPPRI) by EUROCONTROL. Its presence in the Manual, in the form of a recommendation addressed to pilots and ATC, appears to be not adequate to the importance of the issue. Recommendations in b) address critical issues as well, still related to the interaction between pilots and controllers. Recommendations in c) and d) can contribute to enhance controllers’ and pilots’ situation awareness. Still, to leave the application to pilots “good will” appears to be insufficient.

2.4.5 The Manual recommends ANSPs and ATCOs to have implemented safety management systems (SMS) in accordance with ICAO provisions. The obligation for SMS implementation could have been highlighted among “Software” existing requirements and provide basis for new related recommendations.

Most of the recommendations for ANSPs and ATCOs are understandable, such as the need for a clear method to indicate that a runway is obstructed, ATC en-route clearance prior to taxi, stop bars switched on and no ATC clearances to cross an illuminated crossbar, the use of runway designators for clearances with runways involved and the adoption of standard taxi routing. Furthermore, ANSPs are recommended to assess existing visibility restrictions from the control tower, which have a potential impact on the ability to see the runway and non visible areas should be clearly identified on a hot spot map. Such assessment responsibility should be shared with the AO, in relation to visibility restrictions other than the tower frame in itself (terminal and office buildings, hangars, lighting towers, etc.) and that removal or the prevention of a (future) visibility restriction should be inserted in the airport master plan.

2.4.6 The Manual addresses the AOs and vehicle drivers. Recommendations such as to conduct operations and infrastructure in accordance with ICAO Annex 14 Aerodromes, implementation of formal driver training programs and safety management systems are logical and understandable. Some of them are the same already listed for pilots (communications, situational awareness, etc.).

2.5 Chapter 5 addresses the incident reporting and data collection, and explains the objective to promote the use of a standardized approach for reporting and analysing information on runway incursions. Very important is that ICAO stresses that incident reporting and data collection is best collected in a “just culture”. The chapter lists in detail how incidents must be reported and hereby referring to ICAO Annex 11 Air Traffic Services, ICAO Annex 13 Aircraft Accident and Incident Investigation, and ICAO Doc 4444 PANS-ATM. The Manual addresses the initial runway incursion notification form and the runway incursion casual factors identification form in Appendixes F & G.

2.5.1 Reading chapter 5 it could appear that the mentioned method only applies to runway incursions that have already occurred, and that the only way to identify causes and contributory factors to runway incursions is the reactive one. But to prevent runway incursions, it is also very important that potential causes are also outlined through available means, although the aim of this chapter only is to promote incident reporting.

2.5.2 Para 5.1.2 states:

“each State can contribute to a full understanding of how individual errors evolve into runway incursions and potential collisions, leading to the development and implementation of effective mitigating measures”.

This appears to pinpoint to human errors, just before the “Just Culture” paragraph, instead of also addressing systemic failures. The cited individual human errors may only represent active failures leading to a runway incursion. Effective mitigating measures require the identification of the latent failures behind them, and after identifying a cause or contributing factor, the first attempt should be the hazard removal.

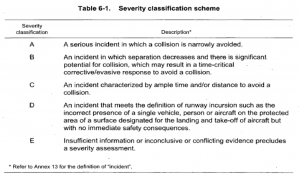

2.6 The objective of runway incursion severity classification is to produce and record an assessment of each runway incursion. All runway incursions should be adequately investigated to determine the causal and contributory factors and to ensure risk mitigation measures are implemented to prevent any recurrence. This classification is supposed to aid in effective data sharing and global harmonization. The Manual subsequently outlines the classification scheme and factors that influence severity.

2.6.1 The classification of the severity of the runway incursion is not related to the definition mentioned above but only according to different situation that can occur at the airport.

2.6.2 The Manual classifies the runway incursion in 5 different classes:

2.6.3 Classification of runway incursions could be useful for statistics and research, therefore a scheme should be maintained to secure proper handling and reporting. However, it could be more useful to identify the scenario rather than the outcome. In fact, a scenario classification could help in investigating the causes while, on the contrary, a severity classification cannot, since minor differences in speed or time could easily change the outcome of a runway incursion.

2.7 The appendices of the Manual are quit extensive. The Manual starts with Appendix A (Communication Best Practices) and lists several earlier mentioned recommendations. Further, the Manual states that the use of standard ICAO phraseology is essential for the prevention of misunderstandings and to reduce the time required for communications. The Manual recommends read-back procedures for vehicle drivers (although not required by ICAO). The use of read-back procedures should be mandatory for vehicle drivers in the manoeuvring area.

2.8 Appendix B (Best Practices on the Flight Deck) lists a lot of recommendations and checklists for pilots. Critical phase of the flight, planning for taxi operations, aerodrome familiarization and briefings are the main subjects addressed in the Appendix. Also situational awareness and stop bars are issues mentioned in regard to best practices on the flight deck.

2.9 Appendix C (Air Traffic Control Best Practices) explains that the aim of the appendix is to highlight some of the causal or contributory factors that have resulted in runway incursions and which were identified during a runway safety survey in Europe in 2001. According to the Manual, it is usually the responsibility of the ATSP to put best practices in place to prevent runway incursions. The Manual states that the use of standard aviation English as an ATC best practice will enhance the situational awareness. However, this is not mandatory and not even customary at all airports. Since general awareness mostly depends on the language permitted by the Regulator and familiarity by users, the recommendation to conduct all runway operations on the AIR Frequency can only be considered valid if coupled with the requirement for only one language, at a given language level.

2.9.1 The Manual repeats the recommendation on issuing en-route clearances and states that an en-route clearance does not authorize a pilot for take-off or to enter a runway.

The Manual explains the requirements for read-back procedures and points out the responsibility for air traffic controllers to listen to the read-back to ascertain that the clearance or instruction has been correctly acknowledged by the flight deck. The Manual is hereby referring to ICAO Doc 4444 PANS-ATM. For aerodromes with separate ground and aerodrome control functions the Manual stresses that “care should be taken to ensure that the phraseology employed during the taxi manoeuvres cannot be interpreted as a take-off clearance”. The use of standard phraseology should prevent previously mentioned circumstances.

2.9.2 Taxi instructions are addressed with the statement that clearance limits have to be included in a taxi clearance. The Manual also stresses that traffic has to be transferred from “ground” to the runway controller before entering or crossing a runway and advises to use standard taxi routes. The Manual quotes ICAO Annex 2 Rules of the Air and ICAO Doc 4444 PANS-ATM on stop bars, but does not give any recommendations on standards for the use of stop bars. Presently the use of stop bars is not consistent globally, a statement that is supported by the outcome of the Stopbar Survey Report (IFATCA Dec 2008).

2.10 Appendix D is Airside Vehicle Driving Best practices. As a result of local hazard analysis in Europe, the operation of vehicles on the aerodrome airside has been highlighted as a potentially high-risk activity. According to ICAO a vehicle driver training program should be one of the “controlling measures to manage the risk”. Depending on the scale and complexity of the aerodrome and the individual requirements of the driver, the training program should take into account several areas as listed in the Manual. The requirements for the driver should be determined by the scale and the complexity of the aerodrome, and also the training program should include a pass or fail test to obtain an “airside driving permit” (ADP). Vehicle driving, as well as pedestrian operations, on the manoeuvring area influence ATC operations. Pedestrian training should be included in the Appendix. The level of training provided and the modalities for issuing “airside passes” and “airside driving permits” (ADP) should ensure safe operations and safe Controllers/Ground personnel interaction (L-L interface).

2.10.1 The Appendix continues with several requirements to obtain an ADP for vehicle drivers to operate on the manoeuvring area. The Manual also addresses the use and requirements of radiotelephony by vehicle drivers on the manoeuvring area. As “General Considerations” the Manual explains the best way to develop a training program and expresses that the framework of the vehicle driver training program is only to be considered as a guide and based on current good practice.

2.11 The Manual mentions an Aerodrome Resource Management Training Course as developed by Eurocontrol to enhance the team role of all those involved in runway operations. This course could be conducted at individual aerodromes or, alternatively, regional seminars could be organized.

2.12 Appendix F shows the ICAO Model Runway Incursion Initial Report Form that is intended to report the initially known facts of an occurred runway incursion. However, some of the requested information could be rather difficult to initially estimate or determine, like closest proximity in feet and meters. Other requested information could be detrimental to ATCOs and/or other frontline operators, before a thorough investigation has been conducted. For example “Did ATC forget about: An aircraft/person/vehicle cleared onto or to cross a runway?”. In this example, for instance a vehicle driver could fill out this form stating that in his opinion the controller forgot the vehicle, but in reality the runway incursion occurred due to a communication failure. A way to improve the form could be to make the questions related to ATC equal to the ones related to aircraft and vehicles. Specifically, if the questions for aircraft and vehicles are about positive actions taken to avoid or reduce consequences of the incursion, and not “errors”, the same should be done for ATC.

2.13 Appendix G, ICAO Model Runway Incursion Causal Factors Identification Form is an extensive form which gives no guidance by whom it should be filed. Although the form is intended to be an “initial report”, it requests subjective information, not supported by due analysis, rather than facts. This could be detrimental for the involved professionals. A way to improve the form could be to limit questions to known facts, rather than collecting opinions (“what” happened, leaving the “how” and “why” to a formal investigation, according to ICAO Annex 13 Aircraft Accident and Incident Investigation).

2.13.1 The forms in Appendices F and G need to be used with great care. MAs are advised to insist with the national regulator for the proper processing of these forms. Especially in States where “just culture” is not yet established to its full intent, it is strongly advised to insist on strict rules for the proper handling of these forms to prevent abuse by third parties. The forms should be modified accordingly to the principles described in the two preceding paragraphs.

2.14 Finally the Manual addresses the Runway Incursion Severity Classification (RISC) Calculator which is a computer program that classifies the outcome of runway incursions into one of three classifications.

Very useful information and guidance is provided on Aerodrome Runway Incursion Assessment which can be obtained at:

https://www.eurocontrol.int/runwaysafety/public/subsite_homepage/homepage.html

https://bluskyservices.brinkster.net/rsa/

And the ICAO Runway Safety Toolkit that can be obtained at:

Conclusions

3.1 The Manual on the Prevention of Runway Incursions is the first manual that has been published by ICAO on this subject. IFACTA must continue to support ICAO to improve the Manual to increase the level of guidance.

3.2 TOC was considering the possibility to write an IFATCA manual on the prevention of runway incursions, but this would mean two different documents with a lot of similarities, which would not enhance the overall prevention of runway incursions. It seemed better to provide IFATCA guidance to be read in addition to the Manual (Appendix A). This guidance can subsequently be used as IFATCA input in case the ICAO Manual is reviewed. Besides this, IFATCA’s Global Airport Domain Team could also use the guidance as part of an awareness campaign.

3.3 The way the Manual is written is mainly focused on human factors (front line operators). TOC advises MAs to use information in the Appendix A together with the Manual.

3.4 The implementation of the recommendations in the manual will generally lead to enhanced safety, although caution herewith must be taken. The recommendation regarding the use of oblique or angled taxiways could be considered strong enough to become an ICAO Standard. However, as time did not allow for extensive discussion in TOC, it was not considered to recommend Policy. Not all recommendations will automatically increase runway safety. Some situations will require intensive study (i.e. by RST) to determine if the recommendations will be appropriate for that specific local situation.

3.5 The ICAO forms regarding runway incursions should be handled with great care and involved personnel obliged to fill out these forms should be well aware of the consequences that could arise from providing information within these forms. Especially in States where “Just Culture” is not yet introduced, the information spread by these forms could easily be abused.

3.6 Just Culture remains important to ensure safety reporting and to achieve a balance of interests of safety and protection of safety information. Therefore it remains essential to have a clear and comprehensive definition that has the proper significance to guarantee the liability of front line operators. IFATCA has such a definition and this definition remains valid.

3.7 TOC considers the recommendation of ICAO that “pilots should never cross an illuminated crossbar when lining up on, or crossing, a runway unless contingency procedures are in use that specifically allow this” insufficient. ICAO should publish consistent and unambiguous stop bar related Procedures and Standards. Considering this and the outcome of the IFATCA Stop Bar Survey Report 2008, the IFATCA Policy on stop bars needs to be amended. Stop bar contingency procedures should also be addressed by ICAO, as they are currently not.

Recommendations

It is recommended that;

4.1 IFATCA Policy on page 3 2 2 15 of the IFATCA Technical and Professional Manual:

No procedures should be introduced that require the crossing of a stop bar at red.

is replaced by:

Recommended practice “Stop bars shall be switched on to indicate that all traffic shall stop and switched off to indicate that traffic may proceed.” becomes an ICAO Standard.

4.2 IFATCA Policy is:

Contingency procedures should be available for stop bar malfunction.

And is included on page 3 2 2 15 of the IFATCA Technical and Professional Manual.

4.3 IFATCA Policy is:

The ICAO provisions for stop bar related procedures should be made consistent and unambiguous in all relevant ICAO documents.

And is included on page 3 2 2 15 of the IFATCA Technical and Professional Manual.

References

IFATCA Stopbar Survey Report December 2008 (GADT).

The European Action Plan for the Prevention of Runway Incursions.

https://www.eurocontrol.int/runwaysafety/public/subsite_homepage/homepage.html

Appendix A – IFATCA guidance on the Prevention of Runway Incursions

Software issues that may result in Runway Incursions

There is a wide variety of software issues that may constitute latent failure of an airport system, or may lead to Runway incursions. These can span from laws and regulations unable to guarantee the necessary protection to aerodrome surroundings (resulting in too close urban areas and subsequent request for noise abatement procedures impacting on safety of operations), to runway crossing procedures where crossing a runway is required.

Common software issues are:

a) inadequate legislation or regulation defining criteria for:

– aerodrome design;

– aerodrome surroundings protection from settlements.

b) inadequate regulation related to segregation of TWYs and service roads from RWYs;

c) adoption of non ICAO or non standardised phraseology;

d) procedures that allow departures from angled (i.e. rapid exit) TWYs;

e) complicated and/or capacity enhancement procedures to expedite traffic, leading to rushed behaviour;

f) inadequate procedure to indicate to controllers that a runway is temporarily engaged;

g) inadequate workload control procedures in TWR;

h) inadequate communication procedures related to:

– length of the message;

– digit transmission;

– controller transmission while the aircraft is rolling out after landing (when pilot workload and cockpit noise are both very high);

– read-back.

i) inadequate coordination or handover procedures:

– in the cockpit (CRM);

– in the TWR (TRM);

– among all aerodrome parties (ARM);

j) inadequate procedures that require too many head down tasks, both in the cockpit and TWR;

k) inadequate procedures for temporary workings coordination;

l) inadequate AIS updating procedures, leading to incomplete, non standard or obsolete information about the taxi routing to expect;

m) lack of aerodrome map on board the aircraft or vehicle;

n) inadequate training syllabi, OJT, and operational personnel checks procedures.

Hardware issues that may result in Runway Incursions

Infrastructures:

Complex or inadequate aerodrome design significantly increases the probability of a runway incursion. The frequency of runway incursions has been shown to be related to the number of runway crossings and the characteristics of the aerodrome layout. Moreover, temporary workings and modification of lay-outs have been found to contribute in Runway Incursions.

Frequent latent failure relate to:

a) Manoeuvring area issues:

-

- RWYs crossing RWYs;

- TWYs crossing RWYs;

- Not enough spacing between parallel runways;

- complex and confusing taxiway net;

- Necessity to backtrack on RWYs;

- Temporary workings on manoeuvring area;

b) ATC infrastructure issues:

-

- Inadequate location and height of tower building

- Inadequate design of TWR cabs causing obstruction to visibility on controlled areas;

c) Other airports infrastructures (terminals, hangars, apron lighting towers) causing obstruction to visibility on controlled areas;

d) Inadequate signage and markings (particularly the inability to see the runway holding position lines).

See ICAO Doc 9157 Aerodrome Design Manual, for more detailed guidance on aerodrome design, and ICAO Doc 9184 Airport Planning Manual, for more detailed guidance on airport planning.

Equipment:

Improper equipment design or operation may contribute to loss of situation awareness leading to Runway Incursions. Frequent latent failure relate to:

a) Inadequate controller working position (CWP) obstructing visibility on controlled areas;

b) Inadequate HMIs requiring too much “head down” time, in both cockpits and TWRs;

c) Communication equipment that doesn’t permit to detect blocked transmissions;

d) Inadequate positioning or availability of the required control of stop-bars to the relevant controller;

e) Lack of Surface Movement Surveillance Systems at aerodromes where low visibility operations take place.

Environment issues that may result in Runway Incursions

Environment protection, such as noise abatement procedures, have been found as latent failures in some runway incursion, causing loss of situation awareness for pilots and/or controllers. Environment may also cause obstruction to visibility, whether vegetation is not properly controlled by airports or authorities over the territory around the airport. Frequent environment latent failures relate to:

a) Frequent change of the runway in use;

b) Use of opposite directions for landing and departing traffic;

c) Presence of vegetation that obstructs visibility.

Liveware issues that may result in Runway Incursions

The following is a list of common liveware issues, found to be contributory factors to Runway Incursions. Deep attention must be addressed to identify the latent failures, present in other parts of the system, inducing the so called “human errors” (active failures).

Cognitive Factors

Most of the human active failures in aviation, included those related to runway incursions, may relay to cognitive factors inducing mistakes. These may be:

a) Controllers momentarily forgetting about an aircraft or vehicle on the runway, or a clearance that had been issued;

b) Pilots or vehicle drivers thinking to be on a location, actually being elsewhere;

c) Pilots or vehicle drivers thinking to be cleared to enter the runway when actually they are not;

d) Pilot and or vehicle drivers accepting a clearance intended for another aircraft or vehicle.

Communication breakdowns

A breakdown in communication between controllers and pilots or airside vehicle drivers is a common factor in runway incursions and often involves:

a) use of non ICAO standard phraseology or, when ICAO phraseology doesn’t cover the circumstance, the use of phraseology non standardised and non shared between parties;

b) a failure by the pilot or the vehicle driver to provide a correct readback of a controller’s instruction;

c) failure by the controller to ensure the readback by the pilot or the vehicle driver conforms with the clearance issued;

d) pilot and/or vehicle driver misunderstanding the controller’s instructions;

e) pilot and or vehicle driver accepting a clearance intended for another aircraft or vehicle;

f) blocked and partially blocked transmissions;

g) overlong or complex transmissions.

Pilot Factors

Pilot factors that may result in a runway incursion include inadvertent non compliance with ATC clearances. Often these cases result from a breakdown in communication or a loss of situational awareness in which pilots think that they are at one location on the aerodrome (such as a specific taxiway or intersection) when they are actually elsewhere, or they believed that the clearance issued was to enter the runway, whilst in fact it was not. Other common factors may be:

a) Pressure due to pilot checks;

b) Inadequate coordination in the cockpit.

Air Traffic Control Factors

The most common controller-related actions identified in several studies conducted worldwide are:

a) failure to anticipate the required separation or miscalculation of the impending separation;

b) inadequate coordination between controllers;

c) inadequate handover between controllers;

d) crossing clearance issued by a ground controller instead of air/tower controller;

e) misidentifying an aircraft or its location;

f) failure by the controller to provide a correct readback of another controller’s instruction;

g) Reduced reaction time due to on the job training in progress.

Airside Vehicle Driver and Pedestrian Factors

The most common driver-related factors are identified in incursions are:

a) Failure to obtain clearance to enter the runway;

b) Not complying with ATC instructions;

c) Inaccurate reporting of their position to ATC;

d) Communication errors.

The objectives of a RST to establish goals to improve the safety of runway operations, listed according to the SHELL Model recommended by TOC:

a) Software:

– improve local rules, regulations, procedures, in relation to operations, training, communication, etc.;

– ensure that procedures and communications are compliant with ICAO SARPs;

– improve runway safety data collection, analysis and dissemination;

– determine, produce and publish hot spot maps;

b) Hardware:

– assess hazards related to aerodrome configuration;

– assess obstacles to visibility from the TWR, both internal and external of the TWR;

– check that signage and markings are ICAO compliant and visible for both pilots and drivers;

– identify potential new technologies that may reduce the possibility of a runway incursion;

c) Environment:

– assess environment protection procedures;

d) Liveware:

– initiate local awareness by developing and distributing runway safety education and training materials to controllers, pilots and vehicle drivers on the aerodrome.

The above goals should form part of a standard “Runway Incursion Prevention Programme”, that should also indicate the responsible organisation and timing for completion.

The RST should have the following requirements:

a) Composition.

The team should consist of management and operational representatives from the main groups associated with manoeuvring area operations: the Aerodrome Management, vehicle driver representative, Air Navigation Service Provider, ATCO Associations, Aircraft Operators and Pilot Associations. The team must consist of frontline operators like ATCOs, pilots and vehicle drivers.

b) Role.

The role of the Local Runway Safety Team should enhance, advising the appropriate management on runway safety issues, hazard removal actions and mitigating measures. Assist in guarding the current topics, develop and run local awareness campaigns.

c) Task.

Identify potential runway safety issues through safety assessment techniques. Use available information and research regarding previous occurred incidents and accidents related to runway safety issues from own and other aerodromes. Investigate runway- and taxi layout, intensity and mix of traffic volumes, visual and non-visual aids (markings, lights, signs, radar, ILS, radio equipment, etc.), ATS procedures, AIP information, etc. Verify that the recommendations contained in the ICAO Runway Safety Manual have been implemented.