59TH ANNUAL CONFERENCE, Singapore, 30 March – 3 April 2020WP No. 159RPAS LicensingPresented by PLC |

| IMPORTANT NOTE: The IFATCA Annual Conference 2020 in Singapore was cancelled. The present working paper was never discussed at Conference by the committee(s). Resolutions presented by this working paper (if any) were never voted. |

Summary

Given the very specific nature of RPAS operations, is the existing licensing system of ICAO annex 1 sufficient to cater for the peculiarities of RPAS pilots, RPA operators to ensure they can safely interact with other existing airspace users? This paper will examine how an RPAS licensing regime might benefit the ATS system.

Introduction

1.1 ICAO (2015) Doc 10019 Manual on Remotely Piloted Aircraft Systems (RPAS), paragraph 2.2.1 classifies an aircraft with no pilot on board as unmanned while an unmanned aircraft piloted from a remote station as a remotely piloted aircraft (RPA).

1.2 The possibility of pilotless aircraft was first mentioned in the protocol of 1929 which amended the Paris Convention of 13th October 1919:

“No aircraft capable of being flown without a pilot over the territory of a contracting State without special authorization by that State and in accordance with the terms of such authorization”.

1.3 As early as World War II, RPAS has presented a challenge to ‘normal aviation’. In recent years one of the greater challenges has been, how RPAS may be safely integrated into an ATM system.

1.4 This is because the use of aircraft (and their associated elements) with no pilot on board, collectively known as unmanned aircraft systems or UAS, has grown over the years from being used mostly for military use to other varied uses such as border and coastal patrols, environmental research, communications, agricultural, digital mapping and planning, fire fighting among other uses. New fields of drone applications include aerial photography, search and rescue operations, shipping and delivery, wireless internet access, law enforcement, wildlife tracking etc. With these varied uses, routine access to civilian airspace is inevitable.

1.5 ICAO Annex 1 – Personnel Licensing details the Standards and Recommended Practices (SARPs) for personnel licensing. However, until 2017, RPAS licensing, as a tool to help integrate RPAS into the ATM system, was not covered in any ICAO document.

1.6 ICAO State letter 12/1.1.22-17/53, dated 3rd may, 2017, proposes amendments to Annexes 1 – Personnel Licensing, 2 – Rules of the Air, PANS-TRG Doc 9868 related to remotely piloted aircraft systems (RPAS). This is an important first step towards achieving a safe integration of RPAS into the ATM system.

1.7 Licences are used because they are an effective mechanism to regulate individuals, companies and organisations, particularly those that perform safety critical tasks. Supported by effective standards, processes and procedures, they can ensure that those performing safety critical tasks are competent. In a similar manner, a licence may be used to ensure that RPAS operations are done within defined standards, processes and procedures.

1.8 The varied types, sizes and usages of drones are big factors to consider when licensing RPAS if we are to safely integrate them into the ATM environment.

Discussion

2.1 RPAS licensing systems already exist in many States.

2.2 Efforts by regulators to manage the introduction of drones into civilian air traffic operations differ from state to state. As drones are used more and more for commercial purposes by companies such as Amazon, Alibaba, DHL, the pressure is on to find better ways to integrate them with existing, manned operations.

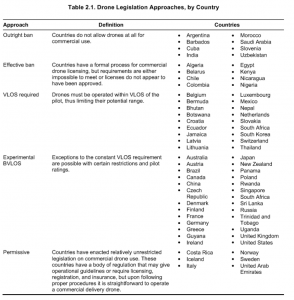

2.3 Approaches to drone regulation differ from state to state, with wide range on the restrictiveness of each element dictated by whether a country favours the promotion of new technology or a safety first approach. (Therese Jones (2017) “International Commercial Drone Regulation and Drone Delivery Services”)

2.4 A typical example of national drone regulation tends to have a pilot’s license, aircraft registration, restricted zones and insurance. The requirements of these elements vary based on drone mass, altitude, use, and pilot experience.

2.5 The regulatory methodologies for incorporating drones into existing systems range from outright bans on the use of commercial drones, through permissive legislation, to a strategy of waiting to observe the efficacy of other nations’ policies before acting.

2.6 The primary obstacle to using delivery drones in most nations is a requirement that drones stay within the pilot’s Visual Line Of Sight (VLOS). Some countries, such as Japan, are experimenting with delivery Beyond Visual Line Of Sight (BVLOS) in restricted areas, with the hope of expanding the program countrywide once effective regulations become apparent.

2.7 Even for countries with existing drone legislation, laws are constantly being re- evaluated. Almost all the laws listed were written or amended within the past two years. While drone laws almost always move toward a more-permissive approach to regulation, the creation of new basic infrastructure may aid in the success of such a transition.

2.8 Specialized training courses, pilot exams based on the type of unmanned aerial vehicle and the conditions under which it operates, and liability insurance to protect against mishaps over populated areas are all mechanisms for ensuring the safety of the general population as usage laws become more permissive.

Therese Jones (2017), International Commercial Drone Regulation and Drone Delivery Services

Licensing Systems

3.1 Licensing systems have the function of ensuring a minimum level of competence, regulating individuals, companies, and organizations, particularly those that perform safety critical tasks.

3.2 Costa-Rica 2019, WP ‘Licensing of ATC’, details the benefits of having a mandatory licensing system for ATC personnel. These same benefits can be transferred to the licensing of RPAS.

3.3 Supported by effective standards, processes and procedures, licenses can ensure that those performing safety critical tasks are competent. In a similar manner, licenses can be used in order to ensure RPAS operators adhere to standards, processes and procedures and to ensure they remain competent-which enhances the safe integration of the RPAS into the ATM system.

3.4 There are many types of licensing systems. A tiered licensing system is one of the licensing systems which may help in safely integrating the RPAS into the ATM environment.

Tiered licensing systems

3.5 Tiered means different levels or layers.

3.6 Tiered licensing systems are already used in aviation, teaching and driving. There has been an increased focus on the safety function of licensing systems over time.

3.7 Licensing of pilots and air traffic controllers based on type, experience, knowledge is very similar to using a tiered/graduated licensing system where one moves from one level to another based on a minimum age, specific knowledge, types of aircraft and airspace knowledge etc.

3.8 An example is whereby, for an air traffic controller to be licensed as an aerodrome controller and to progress from one rating to another, they have to meet minimum qualifications as specified in ICAO Annex 1.

3.9 ICAO Annex 1 specifies types of ratings which an Air Traffic Controller may be given subject to meeting the requirements specific to each rating. These requirements include the subjects which the ATCO must be taught and pass, the pass marks, the age at entry level, the medical fitness and English language proficiency requirements among other requirements. For each rating, different requirements are specified.

The safe integration of RPAS into an ATM system

3.10 The need to safely integrate RPAS into an ATM system through licences has been tackled by different states mostly on the basis of the size of the RPAS. The European Union supports the licensing of RPAS which are more than 25kg only. Official Journal of the European Union of May 2019 (part 14) RPAS are also to be registered and certified based on the risk they present to privacy, protection of personal data, security or the environment.

3.11 Licensing could benefit by integrating RPAS of all sizes into the ATM system as, in many instances, they may have the same risk to privacy, protection of personal data, security or the environment.

3.12 ATC would also benefit from knowing that all operations within the airspace are licensed, meaning they have specific privileges and limitations, they understand the airspace in which they are operating and they know the rules and regulations governing such operations.

3.13 By licensing all RPAS including the privately operated RPAS toys, the licensing authority would be able to ensure that the owners have a minimum level of understanding or specific knowledge that makes them aware of the effect of their operations on general aviation.

3.14 A tiered licensing regime can be used to ensure the safe integration of UAS into the ATM system. An example of how this can be done in stages is where new UAS operators are granted tier 1 licences which would only restrict them to operate a certain class of UAS in segregated airspace, tier 2 for UAS pilots who have more experience and more knowledge to operate in non-segregated airspace, etc.

3.15 Similar to tiered ATC and Pilots Licences, RPAS operators would need to complete written assessments on airspace knowledge, regulations and procedures. A tiered licensing system will allow new RPAS operators to gain experience and skills gradually over time in low risk environments.

3.16 Other means to ensure the competence of RPAS operators may be to:

- specify an RPAS learners period under competent supervision;

- require completion of RPAS education courses;

- conduct written/online examinations; and

- withdraw RPAS licensing from incompetent operators or operators who breach any of the RPAS regulations.

3.17 Prohibitions may be introduced for RPAS operations under certain conditions e.g. under night conditions or in specified airspace classifications. In a graduated/tiered licensing system, more RPAS operator experience would be required prior to full licensure.

State Letter – ICAO proposals for the amendment of Annexes 1, 2 and PANS- TRG (Doc 9868 ) related to remotely piloted aircraft systems (RPAS)

3.18 In the above state letter, ICAO recognized the increased demand for RPAS to operate in non-segregated airspace and aerodromes and the need to develop SARPS and related guidance material in order to safely and efficiently integrate RPAS into the existing air navigation system.

3.19 One of the conclusions of the unmanned aircraft systems study group (UASSG) was that in order to fully integrate unmanned aircraft into non-segregated airspace in a safe, secure and efficient manner, unmanned aircraft must operate in the same manner as other aircraft: licensed and responsible individuals, certification of equipment, and predictable interaction with air traffic control (ATC) and other aircraft, are therefore required.

Since a remotely piloted aircraft (RPA) is a “pilotless aircraft”, the individual controlling the RPA cannot be a “pilot”, as referred to in article 32 of the convention or in Annex 1 — Personnel Licensing. However, in order to convey that the individuals in control have similar basic responsibilities, training, knowledge and skills as pilots, they have been designated as “remote pilots” to distinguish them from traditional pilots. This distinction also requires the establishment of new approaches and solutions that are not always consistent with the current requirements for manned aviation.

2.3.3 Considering that the Convention lacks mutual recognition of remote pilot licenses and taking into account the advice of industry and UAS practices for remote pilot licensing, the RPASP agreed that the State in which the RPS is located is best positioned to assess the competency of the applicant for a RPL.

2.3.4 This approach has several advantages:

a) it facilitates the operation of a foreign RPA in a State’s sovereign airspace, specifically in busy terminal areas where C2 Link performance requirements may necessitate a proximate RPS;

b) oversight of the remote pilot and local operators can be conducted by the local Licensing Authority;

c) the State in which the RPS is located and which issued the licence can have the assurance of training provisions and methods for remote pilots flying in its airspace; and

d) the State of the Operator maintains authority for granting or denying an RPAS operator approval to obtain remote piloting services from a remote pilot licensed by another State.

Conclusions

4.1 There are concerted efforts to address RPAS licensing by all stakeholders.

4.2 There is still no common/universally acceptable way of licensing/regulating RPAS and most of the efforts are at most disjointed and differ from country to country. However, ICAO is making an effort towards reviewing Annex 1 to include RPAS licences.

4.3 Most efforts are geared towards a successful integration of RPAS at high altitudes and not at low altitudes. However, licensing of RPAS should target all sizes of RPAS no matter the area of operation and regardless of the purpose of the RPAS if safe integration is to be achieved since they all present similar risk regardless of the size of RPAS.

4.4 Tiered licensing systems have been used successfully in aviation, driving and teaching. There is evidence to support licensing of RPAS for a safe integration into the ATM system. Depending on the type, size, weight and area of operation, different ‘tiers’ of licence may allow RPAS operators more flexibility for some types of operations.

Recommendations

5.1 This paper is accepted as information only.

References

ICAO (2015) Doc 10019 Manual on Remotely Piloted Aircraft Systems (RPAS) 1st ed, Intl Civil Aviation Organization: Montreal, Canada.

ICAO (2017) Annex 1, Personnel Licensing 11th ed, 174th amendment. Intl Civil Aviation Organization: Montreal, Canada.

Therese Jones, International Commercial Drone Regulation and Drone Delivery Services.

Costa-Rica 2019: WP- Licensing of ATC.

ICAO State Letter (2017) on the proposals for the amendment of Annexes 1, 2 and PANS-TRG (Doc 9868) related to remotely piloted aircraft systems (RPAS) ref.: an 12/1.1.22-17/53.

Allan F. Williams, Earning a driver’s license.

COMMISSION IMPLEMENTING REGULATION (EU) 2019/947 of 24 May 2019 on the rules and procedures for the operation of unmanned aircraft.