62ND ANNUAL CONFERENCE, Montego Bay, Jamaica, 8-12 May 2023WP No. 155Conversion of Military ATCO LicencesPresented by PLC |

Summary

Military Air Traffic Controllers (ATCOs) leaving the military service to commence work in civilian Air Traffic Control (ATC) often have no recognition of their ATC experience or qualifications. This can result in military air traffic controllers having to undertake an initial training course with the associated length of time and cost. This paper looks at what the barriers of converting military qualifications to a civilian air traffic control licence are and what conversion methods are available today and might be available in the future.

Introduction

1.1. There are service men and women leaving the military who, potentially have lots of experience in the ATC profession. Military ATCOs must complete an initial training course with their military organisation to work as a military ATCO. When a military ATCO wishes to commence a career as a civilian ATCO, previous experience and qualifications could allow for a reduction of the training time required to gain a civilian ATCO licence. Often, however, this does not happen. Military controllers, looking to transfer into civilian ATC are, therefore, required to complete the full initial training course as someone with no prior ATC experience.

1.2. A continuing problem in civil aviation is the scarcity of air traffic controllers. To combat this, Air Navigation Service Providers (ANSPs) globally are initiating recruitment drives (https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-scotland-business-45057103). The impact of

these shortages within Europe and around the world causes serious travel disruption, often in peak times.

1.3. Traffic levels during the COVID-19 pandemic plummeted to previously unseen levels. In 2022 traffic slowly returned and forecasts suggest traffic will continue to increase year-on-year reaching pre-pandemic levels around 2024, and then increase by a projected 2-3% every year. All the challenges the industry faced prior to the pandemic will likely return, including constraints on the availability of staff (https://www.adlittle.com/uk-en/insights/viewpoints/act-now-full-digital-transformation-air-traffic-control) (https://www.independent.ie/irish-news/irish-air-traffic-control-in-crisis-staff-claim-as-they-call-for-transport-minister-eamon-ryan-to-investigate-4086503).

1.4. The ability to reduce the training times of military ATCOs could go some way to meeting future demand. There is already a push from aviation bodies (https://www.reuters.com/article/us-europe-airlines-atc-idUSKCN1QN0YH) to reduce the time it takes to train an ATCO. Military ATCOs having to commence their training from the beginning, relearning topics and practices they have already covered before, is time that could be saved. Recognising military qualifications, experience and skills could enable training times to be reduced or eliminated.

Discussion

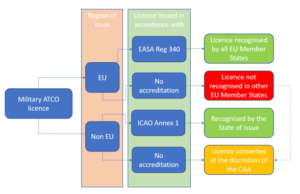

2.1. Military ATCO licences, when issued, do not have to comply with ICAO, as these standards are for civilian air traffic control. They do, however, need to operate in accordance with State requirements and military orders. If a State chooses to, it can apply these standards to military ATCOs who provide services to the public (Regulation (EU) 2015/340 Article 3.1). In the UK, for example, military ATCOs hold “Certificates of Competency” which do not conform to ICAO or EASA standards. France is one example of a State that does issue European ATCO licences to its military personnel (French DGAC CRD-2021 response to Related NPA: 2021-08(A) – Related Opinion 06/2022 – RMT0668 Pg 30).

2.2. Not having a licence in accordance with ICAO standards usually requires military air traffic controllers, upon leaving the military, to have to convert their licence to an ICAO-compliant licence before they can continue their career in civilian ATC. Israel is one of many examples of a State that does not licence its military ATCOs and consequently, all military ATCOs who progress to civilian ATC must successfully complete initial training at an approved Initial Training Organisation (ITO).

2.3. The remuneration and benefits can be vastly different between military and civilian ATCOs. This is not to say the reason for a transfer is about remuneration, but more about the recognition for the experience and skill that military controllers have gained during their service.

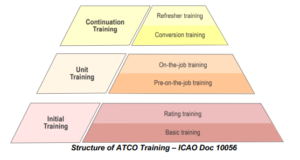

2.4. Civilian ATCOs start their training with initial training which includes basic training and then rating training. On successful completion of this course, the trainee can then proceed to unit training. This initial course can be very time consuming as it is designed to impart the required knowledge to individuals who have no previous ATC experience. This process is to prepare the controller for on-the-job training (OJT) at an ATC unit. With some recognition of the military qualifications and skills, this initial training is one area where substantial time and cost savings could be made. Depending on the previous experience of the military ATCO, the OJT element could also be shortened, reducing the time required for the trainee ATCO to become rated.

ATCO Licensing

ICAO guidance for States’ personnel licensing

2.5. ICAO does not issue ATCO licences. Licences issued by ICAO contracting States on the basis of Standards and Recommended Practices (SARPs) of Annex 1 – Personnel Licensing are habitually called ICAO licences. This has led many to believe that there is a specific ICAO or “international licence”. There is not one single international licence issued by ICAO or any other organisation. States issue their own licences based on national regulations in conformity with Annex 1 (https://www.icao.int/safety/airnavigation/Pages/peltrgFAQ.aspx).

2.6. As stated in a previous IFATCA paper (Licensing of ATCOs WP No. 159, Costa Rica, 2019): Most States have a licensing system for ATCOs. However, although the Standards and Recommended Practices (SARPs) for the licensing of ATCOs are contained within Annex 1, an ATCO licence is not mandatory. Unlicensed State employees may operate as air traffic controllers on condition they meet the same requirements.

2.7. For States who do issue licences in accordance with ICAO, Annex 1 requires applicants to meet specified requirements in respect of:

- Age,

- Knowledge,

- Experience,

- Skill, and

- Medical fitness.

2.8. However, each National Licensing Authority, should it choose to do so, may determine the manner by which knowledge and skill required for licences or ratings are to be demonstrated. The Licensing Authority may choose to accept certain military qualifications and experience as being equivalent to some or all of the knowledge and skill requirements that must be demonstrated by civilian applicants and may issue a licence or rating on that basis (ICAO Doc 9379, 2nd edition – Recognition of military qualification and experience – 2.5.1.2).

2.9. Most commonly, the recognition policy applies to pilots, but it may also apply to other flight crew and air traffic controllers. If military air traffic controllers are not fully familiar with civil operational procedures and operate within accordance with military law and provisions, they should demonstrate the standard and knowledge required by Annex 1 as well as complete no less than three months of satisfactory service engaged in actual control of civil air traffic, under the supervision of an appropriately rated air traffic controller (ICAO Doc 9379, 2nd edition – Recognition of military qualifications of other military personnel – 2.5.3.5). An example is that in Israel, where military ATCOs speak exclusively in Hebrew. Civilian ATC phraseology in English is something they will not be fully familiar with.

2.10. The Licensing Authority is not obliged to accept military experience or qualifications, however, and there may be reasons why the States Licensing Authority is not fully aware of the training received by the applicant. It is essential that the training and capabilities of the applicant are understood. The degree of recognition of skill and knowledge depends on a variety of factors, including the form and content of their military initial and operational training, their recency of experience and their controlling exposure. No single recognition system is appropriate for all States.

2.11. All ICAO Member States have their own methods of training. They set their own objectives, performance criteria and standards so it makes it difficult to recognise the training received elsewhere. If, for example, all States and military organisations would use the ICAO Competency Framework for ATCOs, as contained in the PANS-TRG Part IV Chapter 2 Appendix 2, it would make it easier for the training to be standardised.

2.12. ICAO had invited IFATCA to take part in a Personnel Training and Licensing Exploratory Meeting (PTL-EM) where the objective was to decide how to conduct the much-needed overhaul of Annex 1 on Personnel Licensing, especially for ATCOs. IFATCA wrote a paper with some of the Federation’s concerns and requests with regards to personnel licensing, training and assessment which was supported by EUROCONTROL and many other States and international organisations.

2.13. Following the PTL-EM, IFATCA became a member of the newly reactivated Personnel Training and Licensing Panel in 2020, where work on this overhaul is currently being progressed.

EASA

2.14. Personnel licensing within Europe for ATCOs expands on Annex 1 and is covered in Commission Regulation (EU) 2015/340. The regulation requires each Member State within the EU to train and maintain their ATCOs to the same standard (Regulation (EU) 2015/340). EASA-endorsed licences also meet ICAO standards.

2.15. In Europe, the structure for a harmonised European ATCO licence was developed to enable the licence qualification to more closely match the ATC services being provided and to permit the recognition of additional ATC skills associated with the evolution of ATC systems and their related controlling procedures (https://skybrary.aero/articles/atco-licensing).

2.16. This development of regulation within Europe allows for the freedom of movement of people. An ATCO licence that is issued in a Member State in Europe will allow the holder to use their licence in another Member State. The European licence has proved an effective way of recognising and certifying the competence of air traffic controllers within Europe.

2.17. Common rules for issuing and maintaining licences are essential to maintain Member States’ confidence in each other’s systems. As such, and to adhere to the common licensing rules, the Civil Aviation Authorities (CAA) within Europe will not currently accept a licence issued outside of the European area or issued by a military organisation for exchange.

2.18. This is because the CAA has no knowledge of the ATC training syllabi of courses undertaken by organisations outside the European area and military organisations, and how these compare with regulation 340 training content. As a result, the CAA is unable to recognise the ATC training undertaken in non-EU Member States or by military organisations.

2.19. The result is that, as seen by the above diagram, the Licensing Authority of a State that issues licences for ATCOs that are compliant with ICAO SARPs and the recommended practices contained within the PANS-TRG, could satisfy itself that the military ATCO has met or exceeded some of the requirements for the issue. This option is not available with EASA at this time and as such, a military ATCO in Europe would be required to complete an initial training course before obtaining a civil ATCO licence. There have been occasions where military controllers have left Europe altogether to gain employment in States outside of the EU where their experience can be credited towards the gaining of an ICAO-compliant licence.

2.20. The complex nature of the EASA regulation towards training and the lack of information on how to recognise military experience results in very few States in Europe offering any kind of recognition of military ATC experience.

EASA opinion 06/2022

2.21. For military pilots in Europe, there is EU Regulation 1178/2011. This regulation covers the administrative procedures for aircrew and interestingly, allows credit towards obtaining a Part-FCL licence, for pilots who have previous military service. Where ICAO has guidance in DOC 9379, which can be applied to military personnel in most aspects of aviation, from engineer to ATCO, European regulation at this time will only consider the conversion of military pilots (Regulation (EU) 1178/2011, Article 10).

2.22. EASA has drafted opinion 06/2022 (EASA opinion 06/2022) with the objective to enhance the mobility options and to streamline qualifications for Air Traffic Controllers. This will look to incorporate a control mechanism for the conversion of national military ATCO licences into student ATCO licences.

2.23. EASA state that the reason for this opinion is that the availability of ATCOs in the European Union has been identified as one of the many factors which restrict capacity within the European ATM system, namely the flexibility in the use of ATCO resources.

2.24. Member States expressed to EASA that the possibility to credit the training of military ATCOs, received during their military service, for the purpose of obtaining an EU student ATCO licence, is not foreseen in the ATCO regulation, despite the existing framework explicitly laid down for military pilots.

2.25. The specific objective of the proposal is to:

| Enable the conversion of national military ATCO licences into civil student ATCO licences issued in accordance with the ATCO regulation through a crediting mechanism. This is expected to facilitate the flexible use of the available ATCO resource by enhancing employee mobility, providing equal opportunities (as in the pilot scheme), and helping to prevent civil ATCO shortage. |

EASA Opinion 06/2022 – 2.2 Objectives

2.26. To achieve this in practice,

- An interested military ATCO would have to approach the Competent Authority within the Member State within which their military training took place, and then,

- The Competent Authority would then have to produce a conversion report which should be generic enough to cover existing national military qualifications and privileges and to demonstrate the gap between those and the requirements of the ATCO regulation.

2.27. It should be noted that this process is triggered by an individual who has to approach their Competent Authority. Upon application, the Competent Authority will be required to assess the initial training experience of the applicant and compare it with the initial training content set out in the ATCO regulation. Following the production of the report,

- In case of full equivalence, a student ATCO licence can be issued (Subject to meeting medical fitness and language proficiency requirements).

- In case of identified gaps, the applicant shall undertake and successfully complete an integrative course, and on completion of the course, be issued with a student ATCO licence.

2.28. In view of the above, accomplishing additional training that arises from the conversion report would be less time intensive for the applicant than taking the entire initial ATCO training course.

2.29. This draft opinion is now in the hands of the European Commission, which will discuss it with Member States in October 2022. Member States will vote on the opinion, and they may introduce changes, or even stop the process. If it is adopted, it will be published, and this process may take between 9-12 months. This means it is unlikely that this will occur before conference 2023.

Potential shortcomings and barriers

2.30. The Licensing Authority must be aware of the training received and of the operations or activities conducted. Training, experience and knowledge of the military applicants may differ widely, mainly because military ATCOs work in a wide variety of areas (e.g., army/navy/air force) where their ATC experience will be very different. The Licensing Authority must develop a good understanding of the applicant’s previous experience, and this is no more apparent than in Israel, where military ATCOs speak in Hebrew and must learn the standard English phraseology for civilian ATC.

2.31. One of the difficulties of transferring from military to civil is not just the learning of new topics for civil air traffic but the “unlearning” of methods and techniques that have been used for possibly many years previously. Some controllers who have completed the conversion courses often find they may inadvertently revert to the phraseology associated with their military experience, for example.

2.32. The migration of a large number of military ATCOs to the civilian sphere could adversely affect the staffing levels of military forces and military organisations might want to limit the movement of military ATCOs to retain an ATC workforce. The remuneration and benefits are usually better in civilian ATC and if the licence conversion was an easy process, then the number of military ATCOs leaving might be detrimental to military organisations. Military organisations must consider methods of personnel retention with regard to allowing service members, who have served a minimum number of years, to be considered for transfer into civilian ANSPs.

2.33. The volume of new ATCOs entering the training system could be enough for, or more than the training organisations can manage. Coupled this with the number of military ATCOs wishing to transfer likely being comparatively low, the training organisations might be reluctant to cater for the small number of military controllers looking to convert their licence.

2.34. For any licence conversion, the Licensing Authority must be aware of the training received and of the operations or activities conducted by the applicant. This can be a difficult, time-consuming and costly task with inherent risks and demands on the authorities and this causes a reluctance to invest. Following this, there is a possibility for this analysis to take a lower priority within the Licensing Authority and as such, might not allow for any significant time savings.

2.35. If this is accomplished, however, the licence can be converted relatively quickly. The process in Australia is a good example where the ANSP has created templates after working with the joint-user aerodromes to ensure the training given is efficient and results in a trainee of the same standard expected from the training course.

Use of unqualified personnel

2.36. IFATCA has a robust policy on the use of unqualified personnel which explains that controllers should not be replaced by personnel who do not hold ATC licenses in accordance with ICAO Annex 1.

| TRNG 9.4.2 – Use of unqualified personnel

For the purpose of guaranteeing safety, controllers shall not be replaced by personnel who do not hold ATC licences in accordance with ICAO Annex 1, with the ratings, recency and competency appropriate to the duties that they are expected to undertake for the position and unit at which those duties are to be performed. State Regulators shall recognize the advantages of implementing an ATCO licensing system to provide assurance to domestic and international stakeholders. ANSPs shall recognise the advantages of an ATCO licensing system as an effective tool not only to harmonise ATCO standards but to give an effective, transparent means of providing assurance that ATCO standards are being met and maintained. The functions which are contained within ICAO Annex 1, as being ATC functions shall not be added to the work responsibilities of unlicensed personnel. |

2.37. There have been examples of States replacing licenced ATCOs with unqualified personnel with little to no notice given (IFATCA Press release on the 23rd of September 2022 on the safety of civil operations in West Africa). Some States have then used their unqualified military personnel to provide ATC services. IFATCA has made its position clear on occasions when this has occurred. Not only does it undermine the safety and credibility of the ATC service, but it also undermines the licensing of ATCOs operating within that State.

2.38. The guidance that currently exists within ICAO Doc 9379 and the new framework in EASA opinion 06/2022, would only allow the issuance of a student ATCO licence, which will only permit the pre-OJT and OJT phases of training to commence. It makes no allowance for military controllers or unqualified personnel to remove and replace current ATCOs.

Case Studies

2.39. For this paper, two people who have undergone a transfer from the UK’s Royal Air Force (RAF) to civilian ATC roles were interviewed.

2.40. One controller applied to NATS through the same process that an ab-initio would be required to do. They then carried out their training with no dispensation for previous ATC experience given, and all classes had to be attended and exams passed. On successful completion of the initial training course, they were issued a student ATC licence endorsed by EASA. The controller has since gone on to live training.

2.41. Another UK RAF controller left the military and started a conversion course in New Zealand.

They were required to pass all the ICAO exams and then had to pass a simulator exam and an aerodrome exam before moving into live training. Their previous experience allowed for the simulator training to be skipped to exercise 12 which would have taken approximately 2 to 4 months to get to.

All these elements allowed the course to be reduced to approximately 5 weeks from a usual course length of 8 months.

This controller added that they have never worked so hard in their life, and they have tended to revert to the standard phraseology that they used while in their military service when they were at, or reaching, their mental capacity.

IFATCA Technical and Professional Manual (TPM)

2.42. Currently, there is no policy in the TPM for ATCO licence transferability, nor policy for military licence recognition.

Conclusions

3.1. Traffic levels are beginning to increase up to pre-covid levels and are forecast to exceed them within the next few years. The staffing challenges the industry faced prior to the pandemic will likely return.

3.2. The flexibility of ATCO staffing is one of the factors identified in meeting this challenge. The ability to recognise military ATCO experience and qualifications could enable reduced training times for military ATCOs who are considering a career in civil aviation.

3.3. Guidance exists for Licensing Authorities within ICAO Doc 9379 and proposals are being discussed within Europe to allow the conversion of national military ATCO licences. These processes will allow for recognition of previous training and qualifications and allow for credit towards the issuance of a civilian licence, reducing the time it takes, and therefore cost, for a military ATCO to gain their civilian ATCO licence.

3.4. There are drawbacks, however. Such as a possible reduction of the military ATCO workforce, the potential increase in workload and cost for the Licensing Authorities and the difficulty for the applicant to adopt new methods of civilian ATC and refrain from falling back to previously taught methods.

Recommendations

4.1. It is recommended that the following be accepted as policy and inserted into the TPM:

TRNG 9.6.1 Recognition of prior learning for military air traffic controllers

Previous training, qualifications and experience attained by military air traffic controllers, should be assessed by the appropriate licensing authority and, if relevant, be credited towards the training required to meet the ICAO Annex 1 (or the equivalent State) requirements for attaining a civilian air traffic control licence.

If the military air traffic controller’s previous training, qualifications and experience meet ICAO Annex 1 (or equivalent State) requirements, then the appropriate licensing authority should facilitate the conversion to a civilian air traffic controller licence.

References

ICAO Convention on International Civil Aviation – Annex 1, July 2022, Fourteenth Edition.

ICAO Doc 9379 – Manual of Procedures for Establishment and Management of a State’s Personnel Licensing System, Second Edition 2012, Amendment – 11th March 2022.

UK CAA CAP 1251 – Air Traffic Controllers Licensing, Second Edition, December 2018.

EASA Commission Regulation (EU) 2015/340, Publication date 20th February 2015.

EUROCONTROL Specifications for the ATCO Common Core Content Initial Training, Second Edition, 2nd April 2015.

EASA Commission Regulation (EU) 1178/2011, Publication date 3rd November 2011, Amendment – 12th January 2021.

ICAO Doc 10056 – Manual of ATC Competency-based Training and Assessment, Second Edition, Amendment – 10th November 2022.

EASA Comment Response Document (CRD) 2021-08(A), 1st Sep 2022.

EASA Commission Regulation (EU) 2018/1139 – Article 68.