DISCLAIMER

The draft recommendations contained herein were preliminary drafts submitted for discussion purposes only and do not constitute final determinations. They have been subject to modification, substitution, or rejection and may not reflect the adopted positions of IFATCA. For the most current version of all official policies, including the identification of any documents that have been superseded or amended, please refer to the IFATCA Technical and Professional Manual (TPM).

58TH ANNUAL CONFERENCE, Conchal, Costa Rica, 20-24 May 2019Agenda Item: C.4.4 – WP No. 94IFATCA RPAS / Unmanned Aircraft TeamPresented by David Guerin (Team Coordinator) |

Summary

Much has changed since IFATCA’s first working paper on Unmanned Aircraft (UA) in 2005. Related IFATCA policy exists yet, as with the regulatory framework, it needs updating as technology improves, numbers of flights/platforms and use cases increase exponentially, and new ways of assessing and managing safety risk appear. As UA Traffic Management is defined and its systems move to implementation, the role of ATCOs is being impacting. The IFATCA EB initiated a team to assist IFATCA’s representatives and Member Associations in gaining knowledge and decision making, to influence regulatory bodies and industry groups, and to support the safe, fair, efficient introduction of RPAS/Unmanned Aircraft operations and the benefits they bring.

Introduction

1.1. This report covers the period from May 2018 when I volunteered for the role (as a retired ATCO) until mid-April 2019. The report is longer than normal as it covers the initiation of this team and updates unmanned aircraft activity until now, and also has an appendix presenting guidance material.

1.2. The EB asked for a small team to be brought together to address IFATCA’s needs in regards RPAS and drones and to support the EB, IFATCA representatives and Member Associations (MA’s) in gaining knowledge and decision making.

1.3. Several WebEx’s have been held to define a way to address the impact that RPAS and drones have on ATM and ATC. Priorities have been proposed and further work is being conducted in this area. Priorities were formatted through WebEx’s (Nov. and Dec. 2018) and an internal straw-poll in Q1 2019. The majority of effort is conducted via Basecamp and email.

1.4. A broad range of meetings and workshops have been attended to establish what changes are proposed and assist the decision making process of where IFATCA should best focus its resources and influence, as well as future policy direction. A summary of work being conducted by research bodies, etc. is included in the discussion.

1.5. IFATCA Guidance Material has been produced, focused only on the subject: ‘Guidelines to ATCOs regarding very-low-level drone operations near controlled airports’. An IFATCA White Paper is being drafted; title: ‘Operational Use of Unmanned Aircraft (including Remotely Piloted Aircraft Systems)’. This paper summaries the near, mid, and long-term impact of RPAS and drones on IFATCA and ATC. The guidance material is appended while the challenge statements from the draft IFATCA White Paper are summarised in chapter 2.6 of this report.

1.6. The IFATCA EB would like feedback on low level operations in your country. A survey has been distributed to all MAs, with support from Norway’s NATCA and the Office, and negotiation with EASA. Titled: ‘IFATCA Unmanned Aircraft questionnaire’, the survey introduces the main issues and has an easy to answer range of questions that are deemed valuable to IFATCA decision making and policies. Not many MA’s have participated as yet (9 as of mid-April) so please attend ASAP; closing date is 3 May 2019.

1.7. Please contact david.guerin@ifatca.org or ignacio.baca@ifatca.org with input or offers to assist the IFATCA RPAS and Unmanned Aircraft (drones) team.

Discussion

2.1. In April 2018, EVPT called for a volunteer to be a coordinator to lead a new IFATCA team on drones. Disclaimer: I initially rejected the idea since I recently retired (took voluntary redundancy) from Airservices Australia and have been supporting (mostly voluntarily) the Lake Victoria Challenge, a humanitarian aid cargo drone challenge in Africa. As no-one else volunteered to coordinate the IFATCA team, I offered to help out in May 2018. It is an extremely high workload as we establish the most valuable focal points and create relationships with various research bodies, building on previous excellent work. On a personal note, I am also pleased to assist the U.K. Guild (GATCO) as their RPAS point of contact. I only intend leading the coordination until someone else steps up, then I will provide support as required.

2.2. The team presently comprises eight members, including EVPT and EVPEUR. The EB asked for the size to be contained and member’s details are provided on Basecamp. Please indicate your interest in assisting to either EVPT or Coordinator: IFATCA RPAS Unmanned Aircraft Team.

2.3. International bodies

2.3.1. ICAO RPAS Panel (RPASP): Jeff Richards: IFATCA Member; David Guerin: IFATCA Adviser. Please refer to the conference report: ‘Remotely Piloted Aircraft Systems Panel Representatives’.

The aim of the RPASP work is currently limited to: ‘certificated RPAS operating internationally within controlled airspace under instrument flight rules (IFR) in non- segregated airspace and at aerodromes in the 2031 onward timeframe’ and therefore to identify gaps and propose solutions to address the integration of IFR RPAS into the international ATM system through SARPs and guidance material.

The Panel is very large and meets three times a year, with Plenary Monday and Friday. The seven working groups meet in between; also at F2F meetings and via webex throughout the year.

There are several cross Panel task forces (e.g. SMP/RPASP and ATMOPSP/RPASP), and the UAS Advisory Group that focuses on ‘drone’ activities, particularly gathering Member States and industry experience with UTM (UAS Traffic management, or U- Space in Europe) via RPAS symposiums and DRONE ENABLE events, hopefully to provide guidance towards standardisation.

One of the more interesting and perhaps pertinent changes in ICAO comes from the 13th Air Navigation Conference (Agenda Item 5: Emerging Issues).‘That ICAO: … h) develop, through an appropriate group of experts, Standards and Recommended Practices (SARPs), guidance or “best practices” related to UTM autonomous operations, after States and regions have had sufficient time to test and validate UTM concepts;’. This followed a request from the ICAO 39th Assembly in 2016 for ICAO develop a global baseline of provisions and guidance material for the proper harmonization of regulations on UAS that remain outside of the international instrument flight rules (IFR) framework and overall is a response to pressure from Member States, Associations and industry.

This led to the UAS-AG. It also led to the recently formed Task Force on UAS for Humanitarian Aid and Development (TF-UHAD) to expedite the development of harmonised UAS regulations by CAAs and to support the Secretariat in guiding ICAO Member States, international organizations and industry seeking to leverage the operation of unmanned aircraft for humanitarian aid and development purposes in the absence of clear, enabling regulations at the national level. The work of the TF-UHAD will publish guidance material on the ICAO website in October 2019. IFATCA isn’t directly represented, although I attend on behalf of the Lake Victoria Challenge.

Future RPASP work is focused on rewriting Doc. 10019 the ‘Manual on RPAS’ to provide a broad overview of RPAS operations as well as guidance towards the implementation of the SARPs, and separate the Manual into two distinct volumes:

Volume I – Overview of RPAS International IFR Operations, with a final draft available for RPASP review in June 2020, and

Volume II – Implementation of RPAS Provisions, draft for March 2021.

Furthermore, the RPASP continues work on Annexes with effective dates between 2021 and 2023: Annex 8 and consequential amendments to Annex 2; Annex 10 C2 Generic SARPs; Annex 6 and consequential amendments to Annex 2; Annex 19, Annex 10 C2 Technological SARPs, Annex 2, Annex 11, and Annex 10 DAA. Annex 7 and Annex 2 Appendix 4 having already been completed while Annex 1 was applicable Nov. 2018. This leaves Annexes 3, 4, 9, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17 and 18 as future work, while Annex 5 is untouched by RPAS!

2.3.2. Joint Authorities on Rulemaking for Unmanned Systems: JARUS is made up of the Stakeholder Consultation Body (SCB) and seven work groups. Plenary meets twice a year, comprising the SCB. Plenary meetings and WG sessions. Individual WGs meet also during the year. IFATCA’s Jens Lehmann is the alternative lead of the Community of Interest 4 –ANSP and controllers, UTM/U-Space providers so attends SCB, Plenary and WGs.

JARUS have formulated the Specific Operations Risk Assessment (SORA) process to provide guidance to CAAs and operators on what is required for a CAA authorisation to fly in a given operational environment. It is a multi-stage process of risk assessment that does not, however, consider, for example, wake turbulence/adverse weather, UA to UA encounters, lost C2 link, in its Air Risk Class. It is also qualitatively based rather than quantitative (numerical data). The two main types of risks addressed are air risks (collision with a manned aircraft or another UA); and ground risks (collision with persons or critical infrastructure). Edition 2 was published in Jan. 2019, along with six of ten planned supporting annexes. The SORA is aimed towards the ‘Specific’ category of UA and matches the EASA UAS operations classification. Please refer to the ECA: Specific Operations Risk Assessment (SORA) – ECA Position Paper (pub. 28 Jan. 2019) for a more detailed critique.

EASA classifies the three categories, considering the risks involved, as “open”: requires neither a prior authorisation by the CAA (or competent authority), nor a declaration by the UAS operator before the operation takes place; ‘specific’ requires a prior authorisation by the CAA taking into account the mitigation measures identified in an operational risk assessment (except for certain standard scenarios); and ‘certified’ requiring full certification of the UA and its operator, as well as licensing of the flight crew.

2.3.3. Consideration of other entities and the value of IFATCA’s involvement:

IFATCA has approached the Guild of The Global UTM Association (GUTMA) to negotiate a mutually agreeable involvement (GUTMA becoming cooperate members of IFATCA, IFATCA getting free access to GUTMA) but is so far unsuccessful. In the meantime, GUTMA has accepted an IFATCA representative pending payment of membership, however, the EB is concerned this may signal our support for GUTMA policies. Many ATM system providers and ANSPs and their UTM subsidiaries are members, along with UTM service providers. It is well worth IFATCA keeping abreast of UTM developments. “GUTMA is a non-profit consortium of worldwide Unmanned Aircraft Systems Traffic Management (UTM) stakeholders. Its purpose is to foster the safe, secure and efficient integration of drones in national airspace systems. Its mission is to support and accelerate the transparent implementation of globally interoperable UTM systems.”

IFATCA was approached to join several work groups (including an ANSP focus group) of UVS International, considered a lobby group related to UAS. UVS organizes conferences and IFATCA has participated before, along with publishing articles and distribution of magazines. Again, it was decided that IFATCA shouldn’t be involved at this stage.

2.3.4. EUROCAE: Please refer to the report of our EUROCAE representative.

2.4. European bodies

2.4.1. SESAR: With regard to drones, the SESAR Coordinator covers the rulemaking activities.

SESAR Joint Undertaking has published various studies and has many RPAS/drone projects:

- European Drones Outlook Study; Nov. 2016.

- European ATM Master Plan: Roadmap for the safe integration of drones into all classes of airspace; Mar. 2018.

- U-Space Blueprint; Dec. 2018.

- CORUS: U-space Concept of Operations is a SESAR2020 Exploratory Research Project from Sep. 2017 to Aug. 2019, with ten related demonstration projects and eight sibling projects simultaneously exploring technology questions. Through the connections of IFATCA’s LOEU/SESAR Coordinator, IFATCA is now involved in this work. The ConOps divides very low level (VLL) airspace into different parts according to the services provided:

- X: No conflict resolution service is offered.

- Y: Only pre-flight conflict resolution is offered.

- Z: Pre-flight conflict resolution and in flight separation are offered. Z may be sub-divided into Zu and Za, controlled by UTM and ATM respectively. Za is controlled airspace.

- The safety risk approach within CORUS is called MEDUSA: Methodology for the U-Space Safety Assessment, and is closely based on the JARUS/EASA SORA approach, yet divides the risk into three (rather than air and ground) by adding an extra risk factor: “Incursion into ‘no fly zones’ so airspace infringement.”, that is considered already within the two basic risk areas of the SORA. This highlights the complex nature of qualitative contemporary safety approaches and different approaches used.

2.4.2. EC DG-MOVE: European U-Space Demonstrator Network. This network has progressed very far already in Europe, with ANSPs, regulators, R&D groups/SESAR Horizon 2020, being involved, however, little has been heard from our MAs and ATCOs.

A large number of ANSPs attended, with presentations from cross border operational trials of UTM, BVLOS flights in CTRs, and urban air mobility projects.

U-Space projects under Horizon 2020, additional to CORUS mentioned above, are:

- Ground based technologies for a real-Time Unmanned Aerial System Traffic Management System (CLASS);

- Sense and avoid technology for small drones (PERCEVITE);

- Technological European Research for RPAS in ATM (TERRA);

- An integrated security concept for drone operations (SECOPS);

- Drone European Aim Study (DREAMS);

- Information Management Portal to Enable The Integration of Unmanned Systems (IMPETUS);

- Drone Critical Communications (DROC2OM);

- Proving Operations of Drones with Initial UTM (PODIUM);

- Advanced Integrated RPAS Avionics Safety Suite (AIRPASS);

- Keeping drones safely fenced off (Geosafe).

An example, PODIUM, is a two-year project, finishing at end of 2019, and will perform four large-scale demonstrations, involving over 185 drone test flights at Odense in Denmark, Bretigny and Rodez in France, and Eelde in the Netherlands. Unmanned Traffic Management solutions will be demonstrated for VLOS and BVLOS drone flights. The scope covers very low level operations in rural and urban areas, in the vicinity of airports, in uncontrolled and controlled airspace, and in mixed environments with manned aviation. Again, through the connections of IFATCA’s LOEU/SESAR Coordinator, IFATCA is now involved in this work.

2.4.3. EC DG-MOVE: Informal Drone Experts Group. Coordinator of the RPAS UA Team will attend future meetings on behalf of EVPEUR. Its task is to act as a sounding board for the conception and implementation of the EU drone policy while advising and assisting the Commission with the implementation of actions to foster and accelerate the integration of drones in the aviation system. Also through the emergence of a suitable operational environment and infrastructure for drones flying at low altitude. The next meeting is May 2019.

2.4.4. In Nov. 2018, EUROCONTROL in partnership with the European Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) published their UAS ATM Integration Operational Concept in conjunction with three discussion documents on topics essential to its implementation: flight rules, airspace assessment, and a common altitude reference system (CARS). It is technology agnostic as it has a ten year or more planning horizon, meaning much of our present technology will change, by replaced by presently unknown technology or cease to exist. The next steps include an airspace assessment for Riga city, airport and CTR. The UTM – ATM ConOps includes extended airspace categories (Very Low Level LFR and High Level Flight HFR rules). Automated flights must be able to apply these flight rules. IFATCA will continue to build up our relationship with this group. Eurocontrol hosted a UAS ATM Webinar in Jan. 2019 with 218 attendees (which I joined). The next steps are webinars for the three discussion documents on May 13th, 15th and 22nd 2019 (which I will also join).

2.4.5. Historically, EASA only provided a regulatory framework for members in the EU for UAS over 150 KGs. From February 2019, harmonised rules for all drones were brought one step closer. By 2022, the transitional period will be completed and the regulation 2018/1139 will be fully applicable. Implementation of the Implementing Act/ Delegated Act is expected in April 2019. Next steps, to finalise development of necessary Acceptable Means of Compliance and Guidance Material by Q2 2019.

Future activities are focused in the ‘certified’ category, with the concept presented to EASA high management in Feb. 2019, then a meeting with European Stakeholders will be organised, NPA publication is expected in Sep. 2019. Standard scenarios (repeatable sorties) based on operator declarations will be prepared, with Direct Publication Opinion planned for Q4 2019 and the first two scenarios are based on scenarios already used in France and Spain. Predefined Risks Assessment through AMCs will also be developed by JARUS and published as soon as the regulations are published; followed by an additional two scenarios by the end of 2019.

Also U-Space. High level regulatory framework work is progressing and includes: definition of services; requirements for Member States; and requirements for service providers, with the opinion scheduled for the end of 2019.

2.4.6. IFATCA is responding to draft European Defence Agency (EDA) / EASA: “Guidelines for the accommodation of military IFR RPAS under GAT – Airspace classes A-C”. The main purpose of these guidelines is to prepare a ConOps, to describe the best practises currently existing allowing RPAS flights in European non-segregated airspace, and to propose a guidance for the accommodation of military IFR RPAS under GAT in Airspace classifications A, B and C. It aims to facilitate such RPAS transit flights in a short-term, basing proposals on the experience of armed forces of different Member States who have operated MALE6 RPAS in their national airspace for some time. The use of RPAS by the military is increasing and continues to do so and while the core mission of military RPAS will still be conducted in segregated or reserved airspace, there is an increased need to have access to non-segregated airspace notably to transit between home base and mission areas.

This is a good example of a well-meaning effort that applies the JARUS SORA (designed for ‘specific” category operations) to what nominally would be a “certified” operation in complex controlled airspace. The approach used engineers the steps within the SORA to suggest authorisation of such flights be ANSPs and CAAs would be appropriate based on operational tradeoffs, or ATCO providing mitigations outside standard operations, to balance the lack of suitable certifiable technology (such as DAA – especially for non-cooperative traffic, ACASxu).

2.4.7. There are other working groups too numerous to mention here. However, that doesn’t mean they are irrelevant.

2.5. Other

2.5.1. I was honoured to present (via WebEx) to the 2018 29th AFM regional meeting in November in Abuja, introducing: different drone operations and Unmanned Traffic Management; providing a brief history of related IFATCA Policy Statements; and updates on ICAO RPAS work and small Unmanned Aircraft regulations as well as ATC involvement in the Lake Victoria Challenge, Tanzania; finishing with IFATCA’s need for a position paper on drones. A list of related reference document links and answers to questions posed was provided to attendees afterwards.

2.5.2. I was also honoured to present at the 2018 35th ERM Panel Workshop in October in Dublin on Liability and Technology; subject: Drones: ‘automatically disruptive’. This focused on: artificial intelligence associated with drones in ATM; and how ICAO responds to this; how IFATCA’s Policy Statements relate; differences with conventionally piloted aircraft (the pros and cons of POB); impact on the workforce; drone competition experiences; and future issues for IFATCA.

2.5.3. I attended SESAR projects PJ10.05 RPAS Integration exercises:

- V2 002: to safely integrate RPAS traffic in non-segregated controlled airspace, En-Route and TMA, complying with ATC instructions. Aligned with the EASA Certified category and equipped with DAA and interoperable ACAS systems. ATM Procedures is a focal point. And considers loss of C2 link (command and control link) and also radio failure.

- V02 004: to test exercises on the safe integration of RPAS into non-segregated airspace, up to V2 maturity level. The exercise was a Real Time Simulation with RPAS flying in class C airspace equipped with a DAA system and Collision Avoidance function. The exercise explored lost connection (lost C2 link) where separation and collision scenarios were to be tested.

Reports are available via LOEU or IWEN. Many procedures tested do not comply with SARPs or regulations, or ignore other safety issues (e.g. wake turbulence) and the common reply when this is queried is that the efforts are only trials.

2.5.4. PLC invited a review of their paper: ‘ATC education and training relating to RPAS, Unmanned Aircraft, and UTM systems’ and significant changes were proposed that will hopefully lead to a work study in 2019/20 and assist in the update of the ICAO Manual on RPAS, particularly Chapter 14: Integration of RPAS operations into ATM and ATM procedures.

2.5.5. A Joint Statement “We are all one in the sky” was published in April 2019, asking for all stakeholders, new and traditional, to collaborate to keep integration safe, secure, efficient and fair. It is a common declaration of 15 aviation organisations developed to: ‘support the European regulatory authorities in producing a robust, harmonised, EU- wide regulatory safety framework that enables the safe, secure, efficient and fair integration of drones in the aviation system, and fosters broad public acceptance’. There are gaps particular to IFATCA and ATC that are not considered in this statement and this IFATCA Team will examine better processes for raising such issues.

2.5.6. I am the RPAS point of contact for the U.K. Guild (GATCO). I attend, for example, the BALPA RPAS WG; British Standards Institute BSI ACE/20 Unmanned aircraft group; Unmanned Aircraft Systems (UAS) Specialist Group of the Royal Aeronautical Society; Operation Zenith (starting as a program of demonstrations of ATM UTM integration in CTA during live traffic at Manchester airport); ‘VTOL BVLOS, droneport’ governmental Group as an ATC and ATM expert; and support meetings with Parliament and the Department for Transport to discuss vital strategies such as future policies on drones and the Airspace Modernisation Strategy governance structure. This has been great exposure for GATCO, and this relationship can be replicated among other IFATCA Member Associations. If other MAs have already done so, or intend to set up a similar role, please contact the Coordinator of the RPAS Unmanned Aircraft Team (me) to discuss.

2.6. Proposed IFATCA RPAS Challenge Statements (from the draft White Paper)

2.6.1. This chapter proposes areas where IFATCA needs to focus its future resources. The following challenge statements and questions are extra to those gathered in the Guidance Material in the Appendix: “Guidelines to ATCOs regarding very-low-level drone operations near controlled airports” and are summarised from the draft IFATCA White Paper.

2.6.2. Very High Level Operations (above FL600):

Does IFATCA/ATC need/want to be involved in the management of high level operations?

2.6.3. Controlled airspace (below FL600):

RPAS will operate differently from conventional (manned) aviation for the foreseeable future and are typically unable to operate IFR or VFR. There will be operational and technological trade-offs, and probably different safety approaches, to accommodate such flights. Lost link and emergency procedures are examples. Should a variation to IFR or VFR flight category be considered, such as UFR (Unmanned Flight Rules)?

2.6.4. Very Low level (probably below 400 ft AGL) CTA or Non-CTA:

The commonly accepted area for UA operations is not above 400 feet Above Ground Level (not above 500 feet in several Member States). This airspace grab is often supported through quoting the ICAO Annex 2, Rules of the Air SARPs where VFR operations are not below 500 ft AGL. 100 feet between a VFR flight and a remotely flown UA is an untested segregation and has no apparent safety work behind it. Wake turbulence between larger aircraft and small UA has not been researched. Segregation required between UA flying BVLOS and conventional (manned) aviation is also an unknown, as is the lateral and horizontal spacing required between pairs or multiples of UA operations. There are vast differences between navigation and surveillance performance of conventional (manned) aviation and UA. UTM / U-Space are presently in exploratory modes. Trials are occurring. Should a new airspace classification be considered by ICAO (i.e. Class U!)?

Safety work should be conducted to ensure an acceptable level of safety exists between UA / RPAS operating in low level airspace and conventional (manned) aviation. This could be achieved through the application of suitable airspace buffers (for example to include controller intervention buffers) around and above low level operations, of perhaps 500 to 1000 feet. This is controversial as it will restrict access by conventional (manned) aviation to airspace below 1000 or 1500 feet AGL. An interface between this UTM and the present ATM can then be designed from a conservative and safe starting point.

How should the application for and approval of RPAS or UA operations within controlled airspace and near controlled airports be treated? (Refer to the Annex: Guidance Material for further discussion).

2.6.5. Classification of Operations:

What is the IFATCA position on the JARUS/EASA designed categorization of drones (Cat A: Open; Cat. B Specific; Cat. C: Certified), and the application of the Specific Operations Risk Assessment (SORA) as a tool to assess what is required for authorisation to fly UA in any given operational environment?

2.6.6. Degradation of operations:

A lost C2 link leaves the RPA in the same state as a fully autonomous aircraft, which IFATCA POLSTATs are against. A lost link is sometimes treated in a similar manner to a radio communications failure, yet they are vastly different. One solution is to terminate (crash-land) the RPA. How should RPAS emergency and contingency scenarios be treated by ATC and ATM in regard to present ICAO SARPs? Should ATC follow alerting service SARPs in the event of an RPAS emergency?

Conclusions

3.1. The impact of RPAS and drones on the ATM system and the role of the ATCO ranges from minor to extreme. This small IFATCA team is brought together to address IFATCA’s needs in regards RPAS and drones and to support the EB, IFATCA representatives and Member Associations (MA’s) in gaining knowledge and decision making. There is a focus on European activities in this report. This is merely a fact of proximity, as I am based in England.

3.2. Several WebEx’s have been held, many meetings and workshops have been attended, priorities are being prepared and IFATCA work studies, through TOC and PLC, should take these into consideration. IFATCA Guidance Material has been produced (Guidelines to ATCOs regarding very-low-level drone operations near controlled airports) and an IFATCA White Paper is being drafted (Operational Use of Unmanned Aircraft including Remotely Piloted Aircraft System). The latter summaries the near, mid, and long-term impact of RPAS and drones on IFATCA and ATC. The IFATCA guidance material is appended to this report.

3.3. As valuable as wide-ranging agreement on broad issues is (e.g. the joint publication: ‘We are all one in the sky’), there are regulatory gaps not included on when and how ATCOs should separate or (segregate) unmanned aircraft from CPA (manned aircraft), or indeed from each other, how to treat an RPAS after a lost C2 link (therefore substantially in a fully autonomous mode), and how UTM or U-Space services have progressed significantly with ANSPs, regulators, and R&D groups (SESAR Horizon 2020) being involved, while little has been heard from our MAs and ATCOs regarding these projects and trials. This IFATCA Team is attempting to address these gaps.

3.4. Please respond to the IFATCA survey titled: ‘IFATCA Unmanned Aircraft questionnaire’’ The survey introduces the main issues and has an easy to answer range of questions that are deemed valuable to IFATCA decision making and policies.

3.4.1. Please contact david.guerin@ifatca.org or ignacio.baca@ifatca.org with input or offers to assist the IFATCA RPAS and Unmanned Aircraft (drones) team, or indeed take over the role of team coordinator, and I will continue to provide support.

3.4.2. Thank you to all who have given their valuable time to support or be part of the IFATCA RPAS Unmanned Aircraft Team, a special thanks to the SESAR Coordinator and the ANC Representative. IFATCA appreciates all your efforts and benevolence in giving up your free time to help out. And my appreciation to IFATCA for its support.

3.4.3. Thanks to my wife and family for their understanding of my need to volunteer during retirement.

APPENDIX – IFATCA GUIDANCE MATERIAL (April 2019): Guidelines to ATCOs regarding very-low-level drone operations near controlled airports

Introduction

The objective of this discussion and guidance material is to promote and uphold a high standard of knowledge and professional efficiency among Air Traffic Controllers. This document is for: distribution to IFATCA Member Associations and ATCOs; as guidance for IFATCAs’ representatives; and for public dissemination. The guidance material focusses on drones operating very-low-level (e.g. not above 400 ft AGL) near controlled airports, generally within controlled airspace, and either VLOS (Visual line of sight, often described as within 500 m of the drone operator/pilot) or BVLOS (Beyond visual line of sight: outside the VLOS area; where the operator/pilot can no longer provide separation visually).

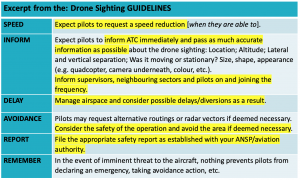

This guidance material complements the IFALPA/IFATCA Drone Sighting Guidelines published 29 August 2018 . It also aligns with IFATCA’s policy statements on the operational use of unmanned aircraft.

Problem statement: The number of drone sightings by pilots and ATCOs and related airprox reports continues to rise. There have been numerous cases of airspace and aerodrome closures due to drones in the vicinity. Many countries do not yet have standard procedures to deal with drone sightings near aerodromes or violations of controlled airspace. Additionally, ATCOs are being asked to assess requests by drone operators for access to ICAO airspace when the rules of the air do not support such access nor provide separation minima for ATC to apply between drones and conventionally piloted (manned) aircraft (CPA). IFATCA policy: ATCOs shall not be held liable for incidents or accidents resulting from the operations of RPAS that are not in compliance with ICAO requirements, in non-segregated airspace.

General notes

1. The scope of ICAO’s work is currently limited to: ‘certificated RPAS operating internationally within controlled airspace under instrument flight rules (IFR) in non- segregated airspace and at aerodromes in the 2031 onward timeframe’ (ICAO Remotely Piloted Aircraft System (RPAS) Concept Of Operations (CONOPS) For International IFR Operations, p. 3). ICAO will expand this scope where evidence indicates unanticipated needs resulting from market growth, technology advances or other unforeseen conditions. ICAO does not consider: fully autonomous aircraft and operations; visual line-of-sight; very low altitude airspace operations (although ICAO has an advisory group: UAS-AG); very high altitude operations; the carriage of persons; non-international operations; as well as droneports, optionally piloted aircraft and scenarios where one pilot operates several flights concurrently.

2. The four main requirements for Unmanned Aircraft System (UAS) – ATM integration are:

- The integration of UAS shall not imply a significant impact on current users of the airspace;

- UAS shall comply with the existing and future regulations and procedures laid out for manned aviation;

- UAS integration shall not compromise existing aviation safety levels nor increase risk more than an equivalent increase in manned aviation would.

- UAS operations shall be conducted in the same way as those of manned aircraft and shall be seen as equivalent by ATC and other airspace users.

3. As of early 2019, Standards and Recommended Practices (SARPs) do not cover the following areas, therefore, the following information is provided by IFATCA to assist MAs and ATCOs in decision-making processes in these areas.

4. During VLOS, the Remote Pilot (RP) maintains direct unaided visual contact with the drone to maintain separation and avoid collisions/hazards. As yet, no reliable airborne nor ground based detect and avoid technology exists to install on small drones, so avoiding other airspace users (cooperative and non-cooperative drones or conventionally piloted aircraft) and airspace hazards (as well as other risks from obstacles, terrain, weather, birds) in BVLOS is problematic.

5. The operation of drones relies predominantly on either C2 links (Command and Control links between the Remote Pilot (station) and the airborne craft) or pre-programmed automation. When this link is sporadic or fails, i.e. a ‘lost’ C2 link, a fully autonomous flight results whereby the operator/pilot cannot interact with the drone. Also, as adequate contingency or emergency procedures are not yet established, integration in non-segregated airspace is not currently an option. IFATCA is opposed to the operations of any autonomous aircraft in non-segregated airspace.

6. Eventually, an accurate picture of the consequences of a drone colliding with a CPA will be available through damage assessments and other ongoing work. Until these are complete and proven to be accurate, it is assumed the outcome of a mid-air– collision with a drone will be either Hazardous (Value A) or Catastrophic (Value B) as per the ICAO Doc. 9859: Safety Management Manual (It is also clear that drone strikes cannot be classified in a manner similar to the approach with bird strikes), possibly penetrating the cockpit or impacting with a helicopter’s rotor. Any collision should be avoided and this responsibility presently lies with the RP. It is generally accepted that drones under 250 gms are harmless. Training and simulation events for both pilots and ATCOs in coping with such scenarios is highly recommended.

7. Drones entering controlled airspace and operating near controlled airports, change the level of safety risk. This triggers a need to measure, understand and assess the change (ESARR 4 – Risk Assessment and Mitigation in ATM. And Skybrary). For example, IFR flights provided with an ATC control service in controlled airspace have an expectation of full separation from other airspace users. This includes helicopter landing sites, water runways, etc. with no control tower. This expectation of full separation can be misleading as there could now be numerous drones operating in the vicinity of the landing site, either known or unknown to ATC; separated, segregated or not, as the case may be. An overall safety and risk assessment for all hazards so far identified with regard to RPAS operations addresses this change.

8. Drones that may be operating legally under the regulations of several States’ (e.g. not above 400 ft AGL, marginally outside exclusion zones) may potentially still be in near proximity to CPA operations, i.e. the approach path, or the departure path for IFR flights. These no-drone-zones may generally protect large numbers of IFR flights such as those via the ILS. However, not all traffic is perfectly aligned with the ILS, or a standard departure path. Reducing the collision risk requires accurate flight surveillance data and airspace assessments tailored to individual aerodromes. This then improves the process by addressing risk to CPA flights outside the instrument flight paths.

9. Other technology deemed to support robust mitigations to the safety risk of drones operating in controlled airspace needs continued attention. Continued research is essential in the area of drone-detection systems (civil use technology for countering drones), geo-fencing, electronic conspicuity, and drone registration, among other topics. IFATCA policy: IFATCA urges the development and implementation of technology to prevent airspace infringements by Unmanned Aircraft.

10.Wake turbulence and downwash: drones, which are much lighter than most CPA, are particularly vulnerable. Wake turbulence is a very real hazard for drones and can trigger an unrecoverable attitude, loss of propulsion, loss of lift, or instability, which could subsequently lead to a ground collision or a deviation from the ‘authorized’ flight path. The response times by the RP in upset recovery are exacerbated (delayed) by latency in corrective control instructions through C2 links.

11.Safety approach: the vast majority of drones are uncertified, operate without airworthiness approvals, the historical safety data is unavailable, and operators are often not from aviation backgrounds. Drones are unable to interact with other airspace users (e.g. ACAS is not designed for drones (ACASxu for RPAS will not be operational for some time)). their performance is significantly different from CPA, and they have no vision from the cockpit. Therefore contemporary approaches to safety risk management have appeared that address risk by limiting operational parameters, such as the JARUS instigated Specific Operations Risk Assessment (SORA). Albeit robust, these philosophies are moving from infancy to operational implementation and their efficacy is as yet unproven.

12.Communicators with RPs: MAs have reported that for some drone operator’s, the operation of VHF transceivers is unreliable, for example, background noise from wind and the din from nearby cars, the RP’s location on the ground distant from ATC VHF radio farms affecting radio line of sight (RLOS) limiting communication. Traditionally, ATCOs don’t rely on mobile phones as a primary means of communicating with airspace users, whereas this is often the only option for even urgent communications with RPs, whereas it does not have the reliability required to support airspace Required Communication Performance and therefore separation minima, etc.

13.The validity of reports of sightings of drones from pilots, the public, etc. needs to be scrutineered. Individual estimations of size, location and distance may vary depending on many factors, or may even be false.

14. The management of flights at very-low-levels (commonly not above 400 ft AGL) is planned (Unmanned Aircraft Systems Traffic Management, referred to in Europe as U-Space) to be through UTM or U-Space. In response to the vast number of flights expected, these services will often be fully automated and will have interfaces with ATC and ATM systems. Early UTM systems will require segregated airspace as ICAO classification of airspace (i.e. class A to E) is not appropriate. There is also broad industry acceptance that the airspace below 400 ft is free of CPA, and therefore entirely available to drone users and that the lowest VFR altitude of 500 ft as per Annex 2 provides a natural buffer. When considering emergency helicopters, MIL training, gliding, visual flights, etc., this is, of course, incorrect; and, additionally, a 100 ft buffer is not suitable. Further discussion is available in IFATCA’s White Paper: Operational Use of Unmanned Aircraft (including Remotely Piloted Aircraft Systems (Planned for publication in Q2 2019)).

15. MAs have reported the inclusion of an ATCO service as a safety risk mitigation to permit otherwise unacceptable risk in various operational scenarios (such as BVLOS, no Detect and Avoid/DAA) as an alternative means of complying with rules of the air. Care should be taken when ATC might be asked to:

- track the drone on surveillance during lost C2 link. Knowledge of the actual position is more important when there is no pilot on board;

- provide traffic information to the operator/RP on surveillance observed traffic;

- provide traffic information to CPA about drones;

- replace the ‘rules of the air need’ for a full detect and avoid collision avoidance from non-cooperative traffic [i.e. due to a violation of CTA, or an aircraft with an SSR failure/no Mode C].

16. Several Member States have tailored drone operating areas within controlled airspace (example: the FAA LAANC – Low Altitude Authorization and Notification Capability). There is still the possibility that drones might fly-away (lostC2 link), conflicting with other traffic, and procedures for minimising the impact of such scenarios must be considered (such as recording the maximum possible flight endurance notated by the RP at the beginning of every drone sortie, so that the aerodrome can be reopened after propulsion has expired and the risk no longer exists). Alternatively, conventional aircraft may inadvertently violate the airspace containing the grids where drones are operating.

17. Remotely piloted drones with passengers (i.e. urban air mobility) are excluded from this guidance. The consequences of drone flight into terrain is less than for CPA with no people on board, whereas this is not the case for automated taxis and similar concepts with people on board.

Unmanned Traffic Management (UTM), U-Space

Drone flights can be provided with various parts of an Unmanned Traffic Management (UTM) service or U-Space service, assuming the operations are fully contained within segregated airspace. UTM needs an agreed definition, and the interface between ATM and UTM then needs to be defined. The industry norm is that automation will provide this service. However, ATCOs can also be asked to provide a UTM (such as approval; segregation: drone to drone; separation: drone to CPA; FIS; emergency response; sequencing and merging into/out of droneports) in present airspace or future airspace (let’s envisage a new Class U). This is an area which is being focused on by IFATCA and further information and guidance will be disseminated as it reaches maturity.

Drones wanting to operate near controlled airports, generally within controlled airspace

The following are in addition to the general notes above.

Generally, drones are completely different from conventional aviation – except in a purely legal sense that they fly – which complicates their treatment under ICAO SARPs and Member States’ regulations. According to IFATCA policy: All Remotely Piloted Aircraft Systems (RPAS) operations in non-segregated airspace must be in full compliance with ICAO requirements. The most conservative approach would be to prevent Very Low Level (VLL) drones from operating within controlled airspace. This would probably lead to more illegal operations and criticism of ATC.

A common approach by Member States is to establish zones (segregation) within controlled airspace where the risk of collision with CPA is deemed low enough due to a range of responsibilities being deferred to ATCOs. Responsibilities range from applying ICAO separation minima; segregating from CPA based on local instructions; or passing traffic on drone activities to pilots of CPA. Some procedures, however, provide ATCOs with no knowledge of drone activity, merely an awareness that drone zones exist and may be used.

Drone pilots wishing to operate within no-drone-zones, will probably be required to ask permission from the airport’s Air Traffic Control. From experience in other Member Associations, such requests quickly absorb resources and are often not considered to be priority work. Dedicated (staffed) sections have been established elsewhere, usually comprising of members of the CAA and ANSP, to negotiate the means of either complying with regulations or applying exemptions so that ATC can legitimately approve drone operations in controlled airspace. Without clear procedures, different ATCOs may either reject or approve a similar request based on personal knowledge, previous good or bad experiences, operation’s schedule and ATCO education. A clear strategy with guidance in the procedure for applying for permission (authorisation and then approval), agreements with each operator (procedures during a fly-away or loss of control event, during an unexpected change in the traffic picture requiring the drone operation to cease immediately, etc.), is essential.

Approving operations The assessment process of examining requests for drones to operate in CTA – when unable to fully comply with IFR or VFR, and rules of the air for the relevant airspace – must either follow ICAO SARPs (not yet in existence) or be administered via the application of the SMS through workshops, for example with appropriate stakeholders, followed by regulatory support and training of ATCOs. IFATCA policy: Standardized procedures, training and guidance material shall be provided before integrating RPAS into the Civil Aviation System.

In future, we may witness areas where drones have near-exclusive access to low-level airspace (e.g. below 1500 feet) and CPA need approval to enter. It is unknown what vertical division would be most suitable to address segregation and the need for new wake turbulence separation minima for drones and RPAS (as there are no ‘very light’ WT categories, and also the latency of response time to a WT event will be different).

Controlling (‘plugged in’) ATCOs should not be involved in the approval process for drone operations requesting permission to operate VLL in controlled airspace, as it may distract from primary duties. This is known to be occurring already in several States.

The future direction of change in ATM may see the introduction of new airspace categories, such as Class U airspace. And new flight categorisations (extensions of VFR or IFR) such as the proposed Eurocontrol Low level Flight Rules (LFR) and High level Flight Rules (HFR), or discussions elsewhere proposing Basic Flight Rules (BFR) and Managed Flight Rules (MFR).

Another question necessitating further research is to decide the value of displaying position information from VLL drone operations on ATM surveillance display equipment, i.e. the CWP. This area of research will also be monitored by IFATCA.

Unapproved drones near controlled airports, generally within controlled airspace

Violations of CTA, sightings from pilots, public or drone detection systems, flyaway events (due to a loss of control) are all examples of unapproved drones in controlled airspace. IFATCA policy: Contingency procedures and controller training shall be provided for the management of infringements by Unmanned Aircraft.

There are pros and cons to many of the considerations for the ATCOs controlling the airspace. Is there a procedure for providing hazard alerts to CPA on unapproved drone operations? Should the Controlling ATCO vector/reroute CPA away from unapproved drone operations? It is possible the vector may unknowingly place the CPA closer to the drone’s trajectory as its position is most probably not displayed on the CWP and it is unlikely the CPA pilots will sight and avoid the drone. To maintain safety, the ATCOs controlling the airspace may need to close the airspace. Re-opening the airspace can only proceed through an appropriate safety risk driven process.

Suggestions to ATCOs and Member Associations of IFATCA:

Be involved with or even initiate safety risk assessment workshops prior to situations where ATCOs plugged in operationally are asked to decide on having drones within their airspace, vector CPA clear of an area where an illegal operation has been reported, or to reopen the airspace. While international standards and transparent contingency or emergency procedures are lacking, all parties should be aware of every procedure prior to each and every UAS operation in non-segregated airspace.

Remember, the regulations may not support drone operations. Ensure the validity of the rules you are given.

Report and action all drone sightings. Consider also the guidance in this document when it is necessary to close airspace/airports to preserve safety and also for the process of reopening airspace.

Consider/plan your emergency response in reaction to a mid-air collision between a drone and a CPA.

Be cautious if essential communication with the RP is via a hand-held VHF transceiver or mobile cell phone.

IFATCA is working to assist and advise in the development of safe and orderly systems of Air Traffic Control; to ensure the professional voice of its members is represented while protecting and safeguarding the interests of the Air Traffic Control profession; and that we promote safety, efficiency and regularity in International Air Navigation.

The benefits realised from drone operations are significant and valuable to humanity. Safely fostering drone activities is a worthwhile method, balanced with the efficient interoperable operation of the ATM system.