DISCLAIMER

The draft recommendations contained herein were preliminary drafts submitted for discussion purposes only and do not constitute final determinations. They have been subject to modification, substitution, or rejection and may not reflect the adopted positions of IFATCA. For the most current version of all official policies, including the identification of any documents that have been superseded or amended, please refer to the IFATCA Technical and Professional Manual (TPM).

57TH ANNUAL CONFERENCE, Accra, Ghana, 19-23 March 2018WP No. 157Review on Just Culture and IFATCA’s Technical and Professional Manual UpdatePresented by PLC |

Summary

Just Culture has been at the forefront of IFATCA´s professional and legal debates for many years. In the past, several high quality papers on Just Culture have been submitted arguing that Jut Culture is about creating and supporting a learning culture, building an open and fair reporting system, designing safety systems and managing behavioural choices. Therefore, this paper will present a very brief review of the Just Culture concept, propose some changes at the IFATCA´s Technical and Professional Manual (TPM) and provide our Member Associations with some Guidance Material on the Just Culture implementation within aviation organisations.

Introduction

1.1. For more than a decade, aviation related organisations have been advocating a concept of fair treatment of front line operators in case of incident or accident and the subsequent need to report those without jeopardizing the professional career of the reporter. Nowadays it is understood by aviation professionals that this fair treatment need to embrace staff at all levels, first line operators as well as managers. The concept, initially label as “ non-punishing culture” or “blame-free culture” and mainly understood in a context where judicial authorities were involved, has finally been named “Just Culture”. It advocates the necessity to create an atmosphere of trust in which front line operators or other persons are encouraged to provide safety information in order not only to avoid accidents but also to learn from incidents. Just Culture has proved to play a vital role as an element of the safety culture and the Safety Management System programs.

1.2. The aviation society has learned that making mistakes is the inevitable by-product of pursuing success and safety in aviation. Furthermore, the human is the only real-time actor within the system whose role it is to adapt and act accordingly. Therefore it has to be seen not as a source of risks and errors but as a resource of flexibility and resilience.

1.3. A Just Culture environment is meant to balance learning from incidents with accountability for their consequences. Aviation professionals are encouraged to provide and feel comfortable submitting safety-related information with the assurance that they will be treated justly and fairly on the basis of their actions and interactions within the system rather than on the basis of the outcome of those actions. Systemic factors and not just individual actions are to be considered. Rather than individuals versus systems, we should think about the relationships and roles of the individuals in the systems.

1.4. Occurrences investigation is a major component of the organisation Safety Management System (SMS) and Just Culture enhances and strengthen that very SMS. Yet, many organisations do not have a policy to promote Just Culture.

Discussion

2.1 IFATCA defines just culture as “a culture in which front line operators or others are not punished for actions, omissions or decisions taken by them that are commensurate with their experience and training, but where gross negligence, wilful violations and destructive acts are not tolerated” (IFATCA Technical and Professional Manual, Edition 2017, p. 4 2 4 8) This definition of Just Culture was introduced in the European Occurrence Reporting Regulation No 376/2014 (Regulation (EU) No 376/2014 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 3 April 2014 on the reporting, analysis and follow-up of occurrences in civil aviation, Official Journal of the European Union, Brussels, Belgium).

2.2 The purpose of Just Culture is evident: using reporting as a resource to discover how aviation system is performing in order to derive safety interventions. Nevertheless, the emphasis that has been put on gross negligence and its consequences especially when judicial processes are followed, has produced a dualist Just Culture: when a safety event will go to Court or when the safety event remain within the organisation or national regulatory authority.

2.3 Both the International Civil Aviation Organisation (ICAO)(ICAO Annex 13, tenth edition, 18.11.2010) and the European Union (EU) (Regulation (EU) No 376/2014 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 3 April 2014 on the reporting, analysis and follow-up of occurrences in civil aviation, Official Journal of the European Union, Brussels, Belgium) consider that the incident and accident investigation process for civil aviation has been crucial in increasing aviation safety as a result of lessons learned throughout the years. This is a reactive process carried out after accidents. Nevertheless, nowadays safety information is not mainly gathered to understand the reasons of an accident but already before it occurs in order to avoid it (proactive approach). Both ICAO and EU require States to establish mandatory and voluntary confidential reporting systems. This is based on the premise that incidents and occurrences are very often the precursor to unsafe events, deviations from the norm or to accidents. In order to capture this information aviation professionals are required by law to report these events with the understanding that no punitive action (either professional or legal) will be initiated against them unless wilful misconduct or intended destructive actions.

2.4 Keeping up the reporting rate is a different issue. We talk about trust but also about involvement, participation and empowerment.

2.5 Having a clear line beforehand between behaviour that is accepted or unacceptable would be just perfect, however reality shows that this does not work in practice. If there is intent to harm others and there is action towards that intention, then the answer would almost always be unacceptable behaviour but the vast majority of reported incidents are matter of system flaws misjudgements, slips or mistakes. Because of the complexity and uniqueness of each occurrence there cannot be a one-size-fits-all solution and the line would be drawn after the incident is analysed and the judgment made. Furthermore, different people will draw different lines (Dekker, 2009).

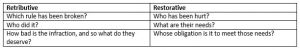

2.6 Inside the organization there are basically two different ways of approaching Just Culture (Sidney Dekker, Just Culture, Restoring trust and accountability in your organization, third edition, 2016) one is based on retribution (by imposing a deserved and proportional punishment), the other is based on restoration (by repairing the trust and relationships that were damaged). In the wake of incidents questions asked are quite different from one approach to the other:

2.7 This “Resilience Theory” (Sidney Dekker, Just Culture, Restoring trust and accountability in your organization, third edition, 2016) is related to Just Culture as it holds that works get done not because people follow rules or prescriptive procedures, but because they have learned how to make tradeoffs and adapt their problem-solving to the complexities and contradictions of the complex system that surround them. This goes so smoothly and so effectively that the underlying work doesn´t even go noticed. Weick and Sutcliffe (2001) held that “safety is a dynamic non-event…when nothing is happening, a lot is happening”. Resilience theory asks “why does it work” instead of “why does it fail”. The work-to rule-strike shows that if people follow all the rules by the book, the system comes to a grinding halt. How is it possible? Because real work is done at a dynamic and negotiable interface between rules that need to be followed and complex problems that need to be solved, so rules get situated, localized, interpreted. And work gets done. This implies a link between the trust that should be part of the Just Culture environment and the organisation´s understanding of how work actually gets done.

2.8 In order to help organisations get familiar with and implement Just Culture, IFATCA´s SESAR/EASA coordinator has submitted lately several papers at which the concept is examined in more depth. For further information, see:

- IFATCA WP No. 163, 53rd Annual Conference, Canary Islands, Spain, May 2014

- IFATCA WP No. 164, 54th Annual Conference, Sofia, Bulgaria, Sofia, April 2015

- IFATCA WP No. 315, 55th Annual Conference, Las Vegas, USA, March 2016

2.9 The intention of this paper is to propose some changes to the IFATCA Technical and Professional Manual (TPM) LM 11.2.1 Just Culture, Trust and Mutual Respect.

Guidance Material

See Attachment 1.

Conclusions

4.1 A basic premise of a Just Culture is that it brings aviation professionals to report safety related occurrences without fearing the consequences. Reporting helps learning and learning improves safety. Therefore, Just Culture is in service of safety and is not a mean of social or disciplinary control. To effect a Just Culture, trust needs to be built between all those who have a legitimate and appropriate interest. The ideals of Just Culture require collaboration and understanding of all those involved, bearing in mind that Just Culture is perishable and therefore requires hard work to be sustained by constant commitment to the ideals and continuous dialogue.

Recommendations

5.1 Following changes in current IFATCA policy on Just Culture are recommended. For a better understanding, the whole policy has been split into different paragraphs.

5.1.1. IFATCA policy is (IFATCA Technical and Professional Manual, Edition 2017, p 4 2 4 8):

A Just Culture in Accident and Incident Investigation is defined as follows: “A culture in which front line operators or others are not punished for actions, omissions or decisions taken by them that are commensurate with their experience and training, but where gross negligence, wilful violations and destructive acts are not tolerated.”

to be read as following:

IFATCA policy is:

Just Culture IFATCA definition is “a culture in which front line operators and others are not punished for actions, omissions or decisions taken by them which are commensurate wit their experience and training, but where gross negligence, wilful violations and destructive acts are not tolerated”

5.1.2 IFATCA policy is:

Just Culture requires a corresponding national legal framework because the administration of justice is the responsibility of States. IFATCA shall encourage ICAO to foster the establishment accordingly in its Member States.

This paragraph to be deleted since it can be misleading because Just Culture is not only about administration of justice. The scope is wider. It´s about many other things but specially about learning from reports, not being afraid of countermeasures when reporting occurrences, its about a resilience tool, about relationships of individuals and systems , about external/judiciary but also internal/within the organisation…

5.1.3 IFATCA policy is:

Member Associations shall promote the creation of mandatory incident reporting systems based on confidential reporting in a just culture among their service provider(s), Civil Aviation Administration(s), National Supervisory Authority(ies) and members.

Member Associations shall promote the creation of voluntary incident reporting systems provided that the reported information will never be used against the reporting person. Compliant with the guidelines of the ICAO SAFETY MANAGEMENT MANUAL.

to be read as following:

IFATCA policy is:

Those Member Associations under national legal frameworks where mandatory and/or voluntary incident reporting systems are not yet compulsory, are encouraged to create one provided it is based on confidential reporting, the reported data shall be protected and never be used against the reporting person nor any other person mentioned in the report and it is compliant with the ICAO SAFETY MANAGEMENT MANUAL guidelines. (ICAO Safety Management Manual (SMM), Doc 9859-AN/474, Second Edition, 2009.) In regard to data protection see IFATCA policy on Use of Recorded Data and policy on Protection of Identity

5.1.4 IFATCA policy is:

IFATCA shall not encourage Member Associations to join Incident Reporting Systems unless provisions exist that adequately protect all persons involved in the reporting, collection and / or analysis of safety-related information in aviation.

to be read as following:

IFATCA policy is:

Just Culture is in the service of safety and by no ways a mean of social control or disciplinary mechanism.

IFATCA shall encourage Member Associations to urge their aviation organisations to develop a Just Culture Policy as part of a mature safety culture. This policy, supported by the highest organizational level and visibly endorsed by workforce level, should include the following elements:

– Just Culture principles ensuring fair treatment of staff at all levels (managers and employees).

– Recognition of staff at all levels for the role they play in delivering a safe service.

– Compromise to provide with the appropriate tools, training and procedures required to perform their job and guaranteeing that they would not be put in situations where safety is compromised because of organizational factors. Anyhow, systemic factors outside the scope of individuals in case of unwanted outcomes are to be considered.

– Means to constantly measure maturity and effectiveness of Just Culture within the organisation.

5.1.5 IFATCA policy is:

Any incident reporting system, including the collection, storage and dissemination of safety related data, shall be based on the following principles:

a) in accordance and in cooperation with pilots, air traffic controllers and Air Navigation Service Providers;

b) the whole procedure shall be confidential, which shall be guaranteed by law;

c) adequate protection for those involved, the provision of which be within the remit of an independent body.

Air Service Providers and their respective employee groups shall develop mechanisms that foster an environment of trust and mutual respect in order to improve the capability to compile, assess and disseminate safety-related information with each other as well as with other national and international organizations.

to be read as following:

IFATCA policy is:

Any incident reporting system shall be based on the following principles:

a) Cooperation: with all those having a legitimate and appropriate interest.

b) Dissemination: distribution of safety-related data to all those with appropriate interest.

c) Confidentiality: for the whole procedure, guaranteed by law.

d) Protection: for those involved or mentioned in the report , the provision of which be within the remit of an independent body.

e) Trust and mutual respect.

5.2 As for TPM LM 11.2.1.1 Just Culture (Guidance Material) it is recommended that:

TPM not to include running pages 317 to 324 ( IFATCA 2016, WP N0.315) since it is in the format of a working paper and its content is already presented under Just Culture Guidance Material as shown in Attachment 1. Any further information about previous IFATCA´s papers on Just Culture can be found at the Discussion chapter of this very paper.

References

Dekker, S.W.A, Just Culture, Balancing Safety and Acountability. Aldershot, UK ;Ashgate, 2007.

Mitchaelides-Mateou S, Mateous A., Flying in the Face of Criminalization, Ashgate, 2010.

Manoj S. Patankar et all, Safety Culture, Ashgate, 2012.

ICAO Annex 13 – Aircraft Accident and Incident Investigation, Eleventh Edition, July 2016.

ICAO Annex 19 – Safety Management System, Second Edition, July 2016.

ICAO Safety Management Manual (SMM), Doc 9859-AN/474, Second Edition, 2009.

Dekker, S.W.A, Jop Havinga, Just Culture: Reporting the Line and Accountability, Journal of Aviation Management, 2014.

Karl E. Weick and Kathleen M. Sutcliffe, Managing the Unexpected: Resilience Performance in an Age of Uncertainty, Jossey-Bass, First Edition, February 2001.

Attachment 1

IFATCA GUIDELINES ON JUST CULTURE

Making a set of guidelines and advice on how to deal with issues concerning ‘just culture’ is at the outset very much about learning about the context in which your organisation is situated. The context of an organisation is inextricably linked to the way that Just Culture can be accepted. Another significant factor is national culture. Being aware of how this might influence the ideals of Just Culture can help MA´s position and find effective ways of undertaking the initial approaches to an organisation’s executive. There are large differences in how people look at and react to those individuals involved in incidents and accidents. Note that the emphasis is not on the circumstances of the event as such, but in the individual person or persons involved closest to the event. In some countries there is no differentiation, legal or disciplanary, between how people are treated after incidents or accidents. In some other countries, individual actions will only be questioned in cases where there are casualties involved. These sitiations require MA´s top ay particular attention to the context in which they are situated and let this inform suitable ways to act accordingly. These guidelines will include guidance on how to learn about the local context as well as how to act within it. Because there is such a range of differences in hw people are treated there can be no clear and definitive answer as to how MA´s have to or should respond when these situations occur. It will be up to the people in the MA´s to take action. These guidelines can only assist the MA´s in their quest for a fair and just treatment of people involved in incidents and accidents.

The dualism of Just Culture:

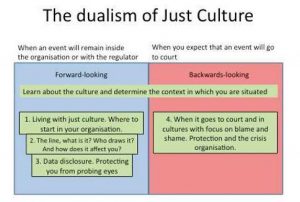

To give an overview, and to help, with the ease of understanding of Just Culture, it is useful to divide these guidelines into two discrete classes. What is referred to here as the dualism of Just Culture:

- What to do when an event will go to court

- What to do when an event will remain within the organisation or with the regulator

There are of course events that will start within an organisation and can then develop into an event that will go to court. These events are few and far between and it will be possible to find support in the guidelines for what to do in the case where your organisation is faced with such an eventuality.

The reason for introducing the dualism of Just Culture is that what the representatives of your organisation can do. The characteristics of the two forms and how those involved act, is very different.

When faced with an event that will go to court the focus will be on blame, shame and the apportioning of responsibility. This is a backward-looking focus, which provides very little help on how to improve safety. The emphasis is on retributive justice.

In the case where an event will remain within the organisation, with or without the regulator or national competent authority, the goal of your organisation should be to continue to focus on improving safety and to avoid that blame and shame will be the focus of attention and the soul driver of actions and decisions. The goal is to create forward-looking thinking about how the organisation and the system can improve. Here the emphasis is on restorative justice.

A staggered approach to JC and changing the discourse

Building Just Culture starts at home from within your own company or organisation. It should be assumed those professionals at all levels give their best possible performance based on their training. An organisation however does not live in a vacuum. Dekker (Dekker, 2007) has taken a position on Just Culture for many years and has proposed a staggered approach to introducing a Just Culture.

Why?

JC is influenced by an organisations cultural context, the way culturally it is situated in society and its relationship with the judiciary and the organisations history itself. A staggered approach makes it possible to match the building of a JC to the possibilities and constraints of an organisation unique cultural attributes. Each step of the staggered approach builds on the previous step and assists in developing confidence trust.

Trust

In the initial steps of instituting a Just Culture, building confidence between organisational actors that helps develop trust in each other cannot be emphasised strongly enough. Just Culture is fragile. It is perishable. It takes only one situation where a decision is questioned or has consequences that are not seen as fair or even unnecessary to undermine a working Just Culture. The confidence and trust that has been built can quickly turn to mistrust in the handling of one event that is perceived not to respect the tenets of Just Culture. Living with JC means beginning to develop a relationship of trust between ATCOs, ATSEPs and ATSAs, managers, regulators and other stakeholders. Then for all involved maintaining this. For some this will be very challenging and will require significant leaps of faith by some stakeholders. It is here that each stakeholder can have significant influence in shaping the way that a Just Culture is enacted.

This will be difficult and challenging, but it is one of the foundations with which to build a Just Culture. One that can withstands storms.

IFATCA extended the staggered approach to the following four steps:

1. Living with JC, where to start in your organisation

2. Living with JC in practice. The line, what is it? Who draws it? And how does it affect you?

3. Data disclosure. Protecting you from probing eyes

4. When it goes to court. The crisis organisation

If nothing else, as a party interested in pursuing a Just Culture in their own organisation, the following facets are those that should be held true to make any progress. These are the areas of importance to any party who are contemplating Just Culture. Even though any progress may be paved with frustration.

Living with JC – Where to start in your own organisation

1. Living with JC, where to start in your organisation

- Advise your members/employees on when to report and what to report. In an organisation with a focus on judging, it is advisable to tell as little as possible.

- If you don’t have an investigation unit – ask for the introduction of incident investigation based on Safety II or other international publications that can support your point of view. Here it is important to be careful, not to develop another tool for management to investigate and then blame the individual.

- Start influencing the general organisational understanding of Just Culture. Here you can make publications available to management and colleagues, which explains incidents as an opportunity to learn instead of blame and shame. This can be part of seminars and workshops.

- Safety means different things to different functions and roles within an organisation. There is not a homogenous view of safety. Begin to discuss with those outside of the operations room how they understand safety, what it means to them in their role.

- Interact with management, explain and discuss the international understanding of ‘Just Culture’ and how people can be treated just after an incident or in the rare case of an accident.

- It is at this stage that developing trust begins – how you interact with the decision makers in the organisation will make a significant influence on the Just Culture discourse in your organisation. As an organisation, you need to prepare for this:

- Develop a sound working knowledge and understanding of Just Culture – prepare yourself and the members/ employees

- As an organisation, understand the differences of interpretation that surround Just Culture that exist within your own environment; discuss these and develop a common view. What expectations does your members or employees have?

- Start to engage with the decision makers in an ANSP and help create the Just Culture discourse. Be patient – Just Culture may be important to employees or members; it may be less so to an ANSP’s management or executive. What expectations do they have? How do these fit with your body?

- Consider other stakeholders outside of the organisation – regulator, other professional bodies, trade unions – who also have an interest in Just Culture and engage with them.

- One of the critical skills that people in your organisation have is to be able to listen to others, to show a willingness to understand others views and perspectives. Their view – even if it is very different from an open-minded Just Culture – is no less valid. Demonstrating this is one step in developing trust – respect for dissenting and different views

- Work on removing organisational disciplinary actions after an incident. Most organisations have a disciplinary regime that has rules and these rules can be negotiated. Use all means to remove the possibility of the people in power to initiate disciplinary actions in the wake of incidents.

- Put CISM (critical incident stress management) on the organizational agenda.

- The interaction with supervisors and the daily operational manager level are especially important because they are the people that deal with individuals immediately after the occurrence. Ask for education and processes for supervisors and other immediate superiors.

- Incident and accident investigation is exclusively about systemic improvements. Make sure that it stays that way and continue to discuss the difference between individual focus, systemic focus and individuals within the system focus.

- Implementing a Just Culture requires preparation, training and commitment. Develop your criteria for implementation and change management programmes. Seek to be a part of this so that your party’s knowledge and understanding of Just Culture can be a trusted resource for an organisation to use in change management and thereby influence the acceptance and application of Just Culture in practise.

- Who draws the line in an organisation – enter into debate and strive for an acceptable working solution for the organisation (and other stakeholders) that is representative of the organisations maturity, understanding and experience of JC. This will change over time – it is not static.

2. Living with JC in practice. The line – what is it? Who draws it? And how does it affect you? And inter-action with authorities

- Just Culture is something that is living. Just because an organisation implements Just Culture one day, does not mean to say that there is no longer any need to work at sustaining and maintaining a Just Culture. Or that there is nothing more to learn.

- Strive for mechanisms where interested stakeholders come together at regular intervals to explore what is happening in an organisation with respect to Just Culture. Do this is in a context of open and honest debate. Use this debate as part of the learning process for all involved including the organisation, and to continue building trust.

- Be mindful of what Just Culture is about – safety of the system. Explore and review how the seed corn of Just Culture – reports – translates into safety interventions. Are the expectations of reporters being met? Often it is the structure and the processes that form the SMS that hinder such improvements. Just Culture can therefore be a means of understanding the effectiveness of the SMS.

- What ownership of safety do those who file reports actually have? Are reports lost in the ‘SMS’ and take on a meaning or interpretation that is not what was intended by those who reported?

- Trust will be tested every time that an event occurs where Just Culture is invoked – legitimately or otherwise.

- The disciplinary regime in your organisation should not be allowed to have any influence on individual competence after workers have been involved in occurrences. Work upon getting people back to work and have them reinstated without any prejudice or stigmatisation. This may prove particularly challenging in small units where everyone knows each other. An independent Critical Incident Stress Management (CISM) unit is a good tool to achieve this.

- Work upon separating investigation of occurrences to a department in your organization that has some independence from the line management. This could be the safety department but also a department within the operational department with special rights and reporting lines. It is important to note that independence within a company is almost impossible. Therefore, it is about creating the best possible organisational independence possible.

- Implement processes that help you as a representative to have influence on how people are treated. This could be in form of participation in the body that decides on disciplinary actions. Examples of this are in place in many organisations, where one or two members of each level of the organisation, both management and those bodies that represent employees, take active part in the collective decision on how to react to individual competence issues after occurrences.

- Participate in the public debate about safety and ‘just culture’ and take contact to the legal departments in the Civil Aviation Authorities if there is one. In many countries there is little separation between authorities and the Air Navigation Service Provider, which makes it both easier but also in some cases more difficult to achieve progress. Be aware of the distinction and who to interact with.

- Seek communication and collaboration with authorities. They often have the goal of increased safety as you have. If possible make them aware of the international rules, especially Annex 13 where it is specifically mentioned that incident and accident investigation is not about blame and liability.

- Be prepared for an event that attracts societies interest to be played out in public and in the media. The consequence of which is that a very different narrative of events can become the focus of attention. This can have unintended consequences and induce unanticipated outcomes.

3. Data disclosure. Protecting you from probing eyes

- Disclosure and reporting are different things. Reporting is the provision of information to supervisors, oversight bodies etc. Disclosure is the provision of information to others outside of this (Dekker, 2013). As a stakeholder, understand the significance and consequences of disclosure.

- The protection of data is helpful for building trust.

- Try to understand how your organisation protects the data that is available. Inform your members/ employees about how the data is being treated and what they should expect in case they are involved in an incident.

- Make sure your organisation builds processes to handle data. Build in safeguards that secure some control of how data are being treated within your organisation.

- Set up national barriers to how the authorities can intervene with investigations and what kind of data they are allowed to use. At least ask for the separation of the investigation board and the relevant, sometimes cross-border authorities.

- Make sure that an Annex 13 investigation cannot be used as evidence to prosecute individuals.

- Seek contact with your CAA, with the aim of building a group of ‘peers’ that can help judge performance in context for the few cases that are going to be probed for legal investigations. This is done in some countries and often avoids that cases end in courtrooms.

- Start the discussion with the prosecuting authority on how to integrate domain expertise to assist them in making judgments and how the authorities can contribute to safety.

- Support your local authorities in the implementation of safeguards for people who report.

- Participate in conferences and join the discussion on Just Culture.

4. When it goes to court and in cultures with focus on blame and shame: Protection and the crisis organisation

- As a stakeholder consider what you will do if one of your members are involved in an accident. Look for a lawyer who has experience with defending people involved in accidents in complex systems or similar. This should be done before one of your members face trouble.

- Recognise that when an event leads to the judicial route, then all parties involved effectively lose control of the way that the matter will be managed. Appreciate the implications of this; factor this into your expectations.

- Ensure that all stakeholders have insurance that cover costs to lawyers and if possible salary in case they are involved in accidents or incidents that end in court (in some cases the company has insurance for all employees, but in other cases you have to cover it from some kind of individual fee).

- Before it happens, make a crisis plan that deals with how you would organise yourself if a member were involved in an accident.

- Review or explore the arrangements that your organisation has for circumstances where a crisis plan is needed.

- After an accident has happened, beware that people will start thinking about avoiding blame and conviction. This can lead to different views on the situation and to situations where two stakeholders are ‘against’ each other.

- Consider whether you want to go against the will of senior management or not. Try to find common ground if possible. Common ground could be to get away as cheap as possible. Remember that going to court is about finding the guilty part and not about improving safety.

- Prepare for the eventuality that the event will become a feature, albeit briefly, of the multiplicity of media sources that are available. It may be that an organisation can provide support and a collaborative partnership in preparing for a very public and potentially ill-informed debate about a member/ or an ANSP’s employee.

- In these circumstances, what are the organisations arrangements for protecting the individuals involved from media contact and intrusions? Does the employer and representative association have such mechanisms in place?

- In these situations there is no one truth. There is no one objective account of what happened.

If nothing else, as stakeholders interested in pursuing a Just Culture in their own organisation, the following facets are those that should be held true to make any progress. These are the areas of importance to any stakeholder contemplating JC. Even though any progress will be paved with frustration.

Other aspects of Just Culture that should be considered

The consequences of dualism in JC

All of the guidelines presented above provide the foundation for the evolution of JC in your organisation. JC is not simple. The nature of the circumstances in which JC is tested is rarely ever simple.

JC can take two or more paths If an organisation finds itself in the situation where it is having to ‘draw the line’ then it needs to recognise that just culture within the organisation is fragile simply because it is perceived that the line needs to be drawn. Where gross negligence is involved more often than not, it is evident that a line has been crossed, usually these are explicit acts calculated to cause harm or embarrassment to the employer/ system.

Information that is gathered by reporting systems is generally in all cases be used for improving organisational safety. Experience would suggest that it is not the case. Using reporting system data to judge Just Culture and to interpret events as gross negligence or not is a misuse of such data. Used in this way it can compromise the trust that is needed for a thriving JC as well as the confidence in disclosing information to the organisation.

Determining gross negligence and reckless behaviour is not a function of event reporting. Other mechanisms and processes will be in place within an organisation that are formalised and designed within the formal arrangements for the handling of such events. To use the incident reporting mechanism in this way is a gross misuse of a process and to use it in a way that it is neither designed nor suited for.

All previous attempts to assess or draw the line such as the substitution test or definitions of gross negligence and reckless behaviour are irrelevant to Just Culture. Because they are inherently tools to make judgments about an individual, frequently outside the context and reality of the operational environment, they inherently lack objectivity and either are, or will be perceived, as principally concerned with retribution.

Drawing the Line

Determining culpability of any kind also directs attention to the organisation that commits the reckless and negligent behaviour: this is often referred to as ‘Drawing the line’.

i – How to deal with it.

Each of these paths of JC will draw upon all that has been gained in building JC – but each path will take a different approach to JC.

In the case where an event takes a path involving the judiciary and ultimately the courts, it is important to appreciate that even the organisation itself will have little influence or control over the events that unfold. In this case, unequivocally – the judiciary will draw the line.

In these cases, the trust between the organisation and its executive and managers and the operational community can be placed in tension. As far as practical working with the organisation can allow for synergies that protect both parties. Whatever the outcome maybe, it is at this time.

ii – Who draws the line?

Where an event occurs that does not follow the judicial path, the question arises who does draw the line? This aspect is one that all stakeholders can develop with their own organisations as they collaborate or work together to realise a Just Culture.

All stakeholders should strive for arrangements where the operational community can have an effective influence on who draws the line. And, moreover, that drawing the line is achieved in a way reflects the realities of the operational practice of the typical day-to-day work. Not to draw the line in the context of work as is imagined.

Further considerations towards a mature JC

The significance and importance of reporting systems and investigation: a persistent feature in the guidelines is the part that reporting systems and the way that investigations are conducted. This should come as no surprise. One way of considering this is that by filing a report it is in essence establishing a contract with the organisation that the act of reporting, and sharing experience of working within the system will lead to a change in the safety of the system. To fulfil this requires a different approach and model of safety from those that prevail in ANSPs today.

As organisations develop an understanding of JC and relationships mature, it will be the case that what is once taken for granted about safety for example is seen in a different light. It is inherent in Just Culture that the place that the human has in interpretations of how untoward events manifest themselves may change. There may be no emphasis on the failure of the human but more on the system itself – system failures. What are called human errors are the outcomes of people having to cope with and adapt to conditions forced upon them to perform beyond their ‘text book’ competences; these forces often include commercial or production pressures, unforeseen dynamics or increases in tempo, etc.

This change in approach may therefore call into question the ways that safety is measured in an organisation. Behavioural observation techniques such as NOSS, D2D can be seen to be incompatible with the underlying philosophy of JC. The emphasis needs to be on system behaviour and not human performance. The human works within a system and therefore the context by which to understand the human’s actions can only be seen through a filter of the system. Techniques such as NOSS and D2D explicitly do not do this.

Language is all important in terms of JC. This is a matter of the nature of the discourse that your organisation undertakes. Occurrence reports can be written in ways that are not indicative of blame or holding the human culpable – they can be written in with neutralised language. Managers and the operational community can strive together to use neutralised language. The operational community themselves can be the harshest critics of others in the operation. Here, the use of non-punitive language can have a significant impact on the JC discourse as well.

Very few stakeholders have influence on organisational disciplinary systems and have no influence on national judicial systems. As a stakeholder it is important to be aware of when you engage in the development of agreements on how to handle these issues.

It is human nature when things go awry for people to distance themselves from the event – to try to keep problems away from the individual themselves. This applies to those inside as well as outside the operational arena: therefore including unit and organisational management and other people who are not directly involved in incidents and accidents but who maybe or who are implicated in some way, such that they will try to reduce anxiety arising from potential harm. This often results in management and other staff not directly involved in the incident or accident, pushing all problems towards the sharp end and away from themselves. For example; pointing at an individual’s competence or performance, or focusing on violations. There is nothing unnatural about this and as Dekker says ‘never underestimate the defence mechanism’.