DISCLAIMER

The draft recommendations contained herein were preliminary drafts submitted for discussion purposes only and do not constitute final determinations. They have been subject to modification, substitution, or rejection and may not reflect the adopted positions of IFATCA. For the most current version of all official policies, including the identification of any documents that have been superseded or amended, please refer to the IFATCA Technical and Professional Manual (TPM).

55TH ANNUAL CONFERENCE, Las Vegas, USA, 14-18 March 2016WP No. 315Just CulturePresented by SESAR Coordinator |

Summary

Just Culture has been at the forefront of IFATCA’s professional and legal debates for many years. This paper reviews the history of the evolution of Just Culture and provides guidance material to assist Member Associations in preparing and sustaining Just Culture in their organisations consistent with the current state of Just Culture.

Lest we forget, the essence of Just Culture is, as argued in this paper, fundamentally to do with making the ATM operation safer in the future. This is, as is argued here, a common aim for all of the stakeholders in ATM.

The paper takes a reflective view of what has been achieved with Just Culture to date.

In so doing, the paper argues that the ideals – the essence – of Just Culture have been lost in its evolution leading to an imbalanced discourse and only a partial or incomplete means to apply the tenets of Just Culture to achieve the ideals.

Furthermore, it provides the staff organisations with possibilities to appeal or have influence on judgments of gross negligence within organisations which are few and far apart.

The paper proposes additional guidance material to the Just Culture Policy.

Introduction

Jung said ‘thinking is difficult, that is why most people judge’. It has taken the aviation industry more than a decade to come to an acceptable definition of just culture, which would stand the test of time. That the aviation industry saw the need for just couture bears out the thinking of Jung. Today it is not uncommon that aviation professionals are judged rather than organisations truly engaging in understanding the nature of unexpected events.

One reading of the specific aim of just culture is to bridge the gap between the needs for, and balancing of, safety and the administration of justice. Another reading of Just culture is balancing the needs for safety with the need for accountability in everyday operational life. In the latter reading of Just Culture, there are two elements that are in tension in the purest (and simplest) consideration of Just Culture:- the judiciary and the operational actors and the organisations that they are situated in. At a global level the aviation side of the balance has published recommended practices (ICAO Annex 13 tenth Edition, 18.11.2010) and explanatory material which reflects the need for careful assessment of the interest of aviation safety and the administration of justice. At the European level European Union (EU) legislation has been passed defining just culture and starting to measure it as part of the EU Single European Sky (SES) performance scheme.

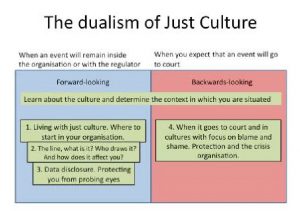

1.1. Considerable emphasis in all that has been undertaken thus far has been placed on interpretation of gross-negligence and the consequences of this. Specifically, in terms of Just Culture and when events are destined for deliberation in a court and follow judicial processes. These are thankfully rare. This emphasis has shaped both the discourse of Just Culture as well as in effect producing a dualist Just Culture. However, the result is that the objectives of Just Culture – making a significant contribution to safety have been lost and supplanted by an emphasis on consequences to the human operators and a need to satisfy bureaucratic accountabilities & obligations. The day to day operation is not supported in situations where Just Culture may be invoked because of the emphasis on the judicial track of Just Culture. The guidelines presented in this paper provide some means to address the skewed emphasis. However, more needs to be done to correct Just Culture and reorient the emphasis towards safety as well as introducing requirements for the protection and appeal rights of individuals within organisations when they are judged or accused of gross negligence.

1.2 The Evolution of Just culture

1.2.1 An examination of the evolution of Just Culture helps situate this papers arguments. The definitions of Just Culture illustrate the emphasis on consequences as opposed to safety. IFATCA (IFATCA Professional and Technical Manual, Edition 2013 p.4247) and The European Union Implementation Regulation (EC 390/2013 OJ L 128/4, 9.5.2013) defines just culture as:

| A Just Culture in Accident and Incident Investigation is defined as follows: “A culture in which front line operators or others are not punished for actions, omissions or decisions taken by them that are commensurate with their experience and training, but where gross negligence, wilful violations and destructive acts are not tolerated.” |

1.2.2. The European Union proposed the Implementation Regulation (EC COM 2012-776.EN.pdf) on amending the occurrence reporting in civil aviation (EU) No996/2010 and repealing directive No 2003/42/EC, (EC No 1321/2007 and (EC) No 1330/2007 proposes the following recitals:

| (31) A ‘Just Culture’ environment should encourage individuals to report safety related information. It should however not absolve individuals from their normal responsibilities. In this context, employees should not be punished on the basis of information they have provided in application of this Regulation, expect in case of gross negligence. (32) It is important to clearly set the line which protects the reporter from prejudice or prosecution by providing a common understanding of the term gross negligence.

(33) Occurrences reported should be handled by designated persons working independently from other departments in order to contribute to the implementation of ‘Just Culture’ and enhance the confidence of individuals in the system. |

And proposes the following articles on protection of the information sources in article 16:

| 1. Each organisation established in a Member State shall ensure that all personal data such as names or addresses of individual persons are only available to the persons referred to in Article 6(1). Misidentified information shall be disseminated within the organisation as appropriate. Each organisation established in a Member State shall processes personal data only to such an extent as necessary for the purpose of this Regulation and without prejudice to the national legislations implementing Directive 95/46/EC. 2. Each Member State shall ensure all personal data such as that names or addresses of individual persons are never recorded in the national database mentioned in Article 6(4). Dis-identified information shall be made available to all relevant parties notably to allow them to discharge their obligations in terms of aviation safety improvement. Each Member State shall process personal data only to such an extent as necessary for the purpose of this Regulation and without prejudice to the national legislations implementing Directive 95/46/EC.

3. Member States shall refrain from instituting proceedings in respect of unpremeditated or inadvertent infringements of the law which come to their attention only because they have been reported in application of Articles 4 and 5. This rule shall not apply in cases of gross negligence. 4. Employees who report incidents in accordance with Articles 4 and 5 shall not be subject to any prejudice by their employer on the basis of the information they have reported, except in cases of gross negligence. 5. Each organisation established in a Member State shall adopt internal rules describing how Just Culture principles, in particular the principle referred to in paragraph 4, are guaranteed and implemented within their organisation. 6. Each Member State shall establish a body responsible for the implementation of this Article. Employees can report to this body infringements to the rules established by this Article. Where appropriate, the designated body shall propose to its Member State the adoption of penalties as referred to in Article 21 towards the employer. |

1.2.3. As shown in the extract above, there is a specific focus on gross negligence in the articles that shape the way that Just Culture is conceived and very limited focus or emphasis on the raison d’etre behind Just Culture – improving safety. Furthermore, these provisions are underspecified in that they are limited in terms of the practical application in the messy details of the real world. Particularly in the case of the determination and assessment of gross negligence. If an event takes the judicial path, it is well understood that it will be the rule of law and judicial process that applies. Within an organisation, it is less clear how such determinations are made. Moreover, it is also not clear how such determinations can be made internally and still uphold the principle of Just Culture. Here, is one example of the dualism of Just culture: where it can be evident the that judicial and organisational paths are different.

1.2.4. Is Just Culture only applicable to Europe? (Baumgartner M., Licu A., Van Dam R., Everything you always wanted to know about just culture(but were afraid to ask) , in Hindsight 18, Eurocontrol, December 2013) No. Just culture is not solely for application in Europe; it is not intended as a solution to a uniquely European problem. Just culture is intended for application and use globally. For a number of reasons, the just culture concept was picked up earlier in Europe, but that does not mean it is restricted to Europe alone. Europe, is a patchwork of sovereign states with sovereign judiciary powers that also has corporatised airlines and air navigation service providers. It has been a good breeding ground for JC. The EU has now enacted JC in its legal orders and regulations.

1.3. On the level of ICAO the issue of the misuse of safety data and protecting safety reporting has been on the agenda for many years. It has become apparent that a key part of the successful implementation of JC relies upon a number of realistic deliverables that will stimulate a further understanding and an active and open coordination between the safety and judicial authorities.

1.4. Therefore, in the discussions and findings of the 36th Assembly, the AIG (Accident Investigation and Prevention) divisional meeting in 2008 and the recommendations of the ICAO HLSC (High Level Safety conference) in March 2010 resulted in resolutions A37-2 and A37-3 of the 37th General Assembly on the sharing of safety information and the protection of safety data. Both resolutions, using the description of the JC initiative, instructed Council to strike a balance between the need for the protection of safety information and the need for the proper administration of justice. The Assembly furthermore noted the need to take into account the necessary interaction between safety and judicial authorities in the context of an open reporting culture. A special Safety Information Protection Task Force (SIPTF) was created as a result of these conclusions. In its final report, the SIPTF recommended a number of solutions, among which close cooperation between Safety, Justice and Just Culture figure prominently. As a result, the new ICAO Annex 19 on Safety Management Systems now contains the definition of Just Culture that also is used by the EU.

1.5. The 38th ICAO Assembly of September/October 2013, amongst other actions, instructed the ICAO Council to take appropriate steps to ensuring and sustaining the availability of safety information required for the management, maintenance and improvement of safety. The Council is asked to propagate the necessary interaction between safety and judicial authorities in the context of open reporting culture, based on the findings and recommendations of the Safety Information Protection Task Force.

Here it is evident that ICAO concern is about the interaction and balance of safety and the administration of justice. There is nothing about the requirements for the protection and appeal rights of individuals within organisations when they are judged or accused of gross negligence.

1.6. The EUROCONTROL Just Culture Task Force has members and observers from US, Australia and Asia and is represented in conferences and workshops globally and in 2008 the FAA and NATCA signed the Air Traffic Safety Action Program (ATSAP), which in the time between 2008 and 2012 (Flight Safety Foundation, Aerosafetyworld, August 2012) had more than 48,000 reports.

1.7. Finally: Just Culture has already conquered New York! When Captain Sullenberger was honoured by the City of New York after his epic ditching in the Hudson River, Mayor Bloomberg gave him a new copy of the book he had to leave in the cockpit. The title: Just Culture (Dekker S., Just Culture, Balancing Safety and Accountability, Alderscot 2007), of course!

1.8. Initiatives such as the Just Culture Model Task Force (Eurocontrol 2012), the joint Eurocontrol/IFATCA (see Agenda item C10.2 Conference 2014) training on prosecutor expert courses, and the advanced arrangement (European Cockpit Association and IFATCA 2012) have been one mechanism that helps foster understanding of the Just Culture principles and contributes to bridging the gap between safety and the administration of justice.

Recent legal proceedings by prosecutors (Switzerland 2013) and court cases (Italy 2008, 10) have shown that the independence of administration of justice will be maintained, even if in certain cases it places elements such as responsibilities of ATCOs and duty of care above ICAO Convention (Anastasi R., Profili di responsabilità penale nel controllo del traffic aereo, UniversItalia, Roma 2011 – ISBN 978-88-6507-203-5).

1.9. The purpose of Just Culture is evident – it is about using reporting as a resource to discover how the aviation system is functioning and performing in order to derive forward – prospective – safety interventions.

It is well understood that aviation has an enviable safety record and the reasons why. To the extent that it has been classified as an ultra-safe system (Amalberti, 2000). The discourse that surrounds Just culture, that was the emphasis in the EU Just Culture charter, is less about safety per se, but is about the role of the human in the system, about the way that the human performs (human performance) and the consequences not only to the individuals involved but also about the consequences to those accountable managers in the management chain (or otherwise) who effectively adjudge an event. The protection of the individual within the organisational context is missing. It is questionable if the tenet of Just Culture is being served by the experience of the last ten years.

Undoubtedly there have been examples of how Just Culture can serve its intended purpose. There are also examples where Just Culture has been administered and has had the opposite effect. Just Culture has been misappropriated and used as a means of social control, as a tool to be used for managerial action in support of bureaucratic accountability. Furthermore it has been misused because decision makers simply have no working knowledge of Just Culture that allows it to be administered in a way that is consistent with the ideal of Just Culture.

Indeed, it is the authors opinion therefore the whole concept of JC is based on arrangements on how to handle issues that have an influence on when and how the disciplinary scheme should be used against individuals who report or have been involved incidents and accidents. As a result, Just Culture is fragile, perishable and can stand or fall on one decision made by an ill-prepared actor. A ‘healthy Just Culture’ can very quickly become the opposite on the basis of one misappropriated event where Just Culture comes into play.

Progressive and forward thinking experts (Hollnagel E., Is justice really important? in Hindsight 18, Eurocontrol, December 2013) who have been developing resilience engineering and Safety II propose the following systemic view on just culture:

| The need for judicial process to parallel safety investigations can be seen as a product of a particular view of safety (Safety-I) and of the search for causes that follows from that. This assumes that the hypothesis of different causes is right, and that people can make a moral judgment on whether what they did was right or wrong. But if the hypothesis of different causes is wrong and that instead people always try to do the best they can, then we cannot claim that it is reprehensible to do what they normally do in cases where the outcome is unsafe, unless we also claim that it is reprehensible in the cases where the outcome is acceptable. The logical consequence of that is that we should not allow people to do what they normally do, but instead oblige them to do what we think they should do (to work as we imagine work should be done). The consequences of that are unpalatable, to say the least. There is probably not much hope of changing the common basis of justice today, which dates from the early sixth century codification of Roman law in Justinian’s Corpus Juris Civilis. Despite the attractiveness and advantages of a Safety-II perspective, we must realistically accept that it will co-exist with a Safety-I perspective for many years to come. But we can at least begin to be mindful about it, so that we do not do things out of habit but rather because they make sense vis-a-vis our purpose. While finding causes and holding people responsible may be reasonable for society and for the general sense of justice, it is of very limited practical value, if not directly counterproductive, for safety and safety management. |

As ATM in some parts of the world progressively evolve different approaches to safety, whilst retaining some of the ‘old’ approaches, other parts of the world will continue with the old ways. The Just culture concept will continue to evolve and most probably will have relevance in the future regardless of the way that safety evolve.

1.10. This paper will provide Guidance Material for the introduction of Just Culture. The guidelines have been developed upon the foundation of:

- Dualism of Just Culture

- Trust

- The discourse of Just Culture

- A staggered approach to Just Culture

Discussion

2.1. Dualism approach of JC

2.1.1. The dualism of Just Culture:

To give an overview, and to help, with the ease of understanding of Just Culture, it is useful to divide IFATCA guidelines into two discrete classes. What is referred to here as the dualism of Just Culture:

- what to do when an event will go to court

- what to do when an event will remain within the organisation or with the regulator.

There are of course events that will start within an organisation and can then develop into an event that will go to court. These events are few and far between and it will be possible to find support in the guidelines for what to do in the case where your MA is faced with such an eventuality.

The reason for introducing the dualism of JC is that what the representatives of an MA can do, and the characteristics of the two forms and how those involved act, are very different.

When faced with an event that will go to court the focus will be on blame, shame and the apportioning of responsibility. This is a backward-looking focus, which provides very little help on how to improve safety. The emphasis is on retributive justice.

In the case where an event will remain within the organisation, with or without the regulator or national competent authority, the goal of the MA should be to continue to focus on improving safety and to avoid that blame and shame will be the focus of attention and the soul driver of actions and decisions. The goal is to create forward-looking thinking about how the organisation and the system can improve system safety. Here the emphasis is on restorative justice.

2.1.2. A staggered approach to JC – changing the discourse

Building a JC starts at home from within an MAs own organisation. But, an organisation does not live in a vacuum. Dekker (Dekker, 2007) has taken a position on Just Culture for many years and has proposed a staggered approach to introducing a JC.

Why?

JC is influenced by an organisations cultural context, the way culturally it is situated in society and its relationship with the judiciary and the organisations history itself. A staggered approach makes it possible to match the building of a JC to the possibilities and constraints of an organisations unique cultural attributes. Each step of the staggered approach builds on the previous step and assists in developing confidence trust.

Trust

In the initial steps of instituting a Just culture, building confidence between organisational actors that helps develop trust in each other cannot be emphasised strongly enough. Just culture is fragile. It is perishable. It takes only one situation where a decision is questioned or has consequences that are not seen as fair or even unnecessary to undermine a working Just culture. The confidence and trust that has been built can quickly turn to mistrust in the handling of one event that is perceived not to respect the tenets of Just culture. Living with JC means beginning to develop a relationship of trust between ATCOs (& ATSEPs and ATSAs), managers, regulators and other stakeholders. Then for all involved to maintain this. For some this will be very challenging and will require significant leaps of faith by some stakeholders. It is here that MAs can have significant influence in shaping the way that a Just Culture is enacted.

This will be difficult and challenging, but it is one of the foundations with which to build a just culture and one that can weather the storms when it is being tested Incidents are often viewed as failures with consequences. Managers have obligations as part of their bureaucratic accountability. Seen in terms of trust, every occasion where a manager adjudges an event in these terms is another nail in the coffin of JC potentially. They also represent opportunities to work together to test knowledge and understanding of Just Culture, but requires patience and non-confrontational approaches by MAs who find themselves in such situations.

An approach of forward looking or prospective safety can be a starting point. One common ground between managers and the operational community is making the operation safer in the future. This is the very essence of Just Culture and building a common understanding of how to achieve this collectively can serve as a building block in the staggered approach

There will be occasions where this relationship of trust will be tested. But handled in a positive and non-confrontational way, each such encounter can serve to strengthen the relationship. Open dialogue where there is an acceptance that there is no black or white answer and multiple perspectives can greatly assist in creating an atmosphere of trust

2.1.3. The discourse of Just Culture

Just culture is not new. Today the discourse that surrounds Just Culture is in large part about consequences and gross negligence. This discourse has taken Just Culture away from what IFATCA believes it is fundamentally about: a discourse about safety and trust.

The Staggered Approach

There are possibilities for MAs to instigate the ANSP to adopt a JC; the staggered approach provides one practical way to achieve this that facilitates trust and confidence in shift to a JC.

2.1.4. The guidelines

Making a set of guidelines and advice on how to deal with issues concerning ‘just culture’ is at the outset very much about learning about the context in which an MA is situated. The context of an organisation is inextricably linked to the way that Just Culture can be accepted. Another significant factor is national culture. Being aware of how this might influence the ideals of Just Culture can help MAs position and find effective ways of undertaking the initial approaches to an organisations executive.

There are large differences in how people look at and react to those individuals involved in incidents and accidents. Note that the emphasis is not on the circumstances of the event as such, but the emphasis is on the individual person or people involved closest to the event.

In some countries there is no differentiation, legal or disciplinary, between how people are treated after incidents or accidents. In other countries individual actions will only be questioned in cases where there are casualties involved. These situations require MA’s to pay particular attention to the context in which they are situated and let this inform suitable ways to act accordingly. These guidelines will include guidance on how to learn about the local context, as well as how to act within it. Because there is such a range of differences in how people are treated there can be no clear and definitive answer as to how MA’s have to or should respond when these situations occur. It will be up to the people in the MA’s to take action and these guidelines can only assist the MA’s in their quest for a fair and ‘just’ treatment of people involved in incidents and accidents.

IFATCA extended the staggered approach to the following four steps:

1. Living with JC, where to start in your organisation.

2. Living with JC in practice. The line, what is it? Who draws it? And how does it affect you?

3. Data disclosure. Protecting you from probing eyes.

4. When it goes to court. The crisis organisation.

If nothing else, as an MA interested in pursuing a Just Culture in their own organisation, the following facets are those that should be held true to make any progress. These are the areas of importance to any MA who are contemplating JC. Even though any progress will be paved with frustration.

2.2. Living with JC – Where to start in your own organisation

| 1. Living with JC, where to start in your organisation |

|

| 2. Living with JC in practice. The line – what is it? Who draws it? And how does it affect you? And interaction with authorities. |

|

| 3. Data disclosure. Protecting you from probing eyes. |

|

| 4. When it goes to court and in cultures with focus on blame and shame: Protection and the crisis organisation.

|

|

If nothing else, as an MA interested in pursuing a Just Culture in their own organisation, the following facets are those that should be held true to make any progress. These are the areas of importance to any MA who are contemplating JC. Even though any progress will be paved with frustration.

In summary:

- A Just culture is in the service of safety. Not a means of social control or a disciplinary mechanism. Be wary of an undue emphasis on gross negligence.

- To effect a Just Culture, trust needs to be built between all of those who have a legitimate and appropriate interest. This is a much larger group than may be initially thought.

- To achieve the ideals of a Just Culture will require collaboration and understanding of others views.

- Just Culture will be tested. Just Culture will be misinterpreted. Each occasion that it is tested or misinterpreted is a learning opportunity for all and can be used to strengthen Just Culture. Be informed to influence these occasions

- Just Culture is perishable. It requires hard work to be sustained by continued commitment to the ideals and by continuous dialogue.

- Just culture is not simple. Each event where Just culture is tested will have its own unique context.

2.2.1. Other aspects of Just Culture that MAs should take into consideration

The consequences of dualism in JC

All of the guidelines presented in the guidance material should be undertaken – to do so provides the foundation for the evolution of JC in your organisation. JC is not simple. The nature of the circumstances in which JC is tested is rarely ever simple.

JC can take two or more paths If an organization finds itself in the situation where it is having to ‘draw the line’ then it needs to recognise that just culture within the organisation is fragile simply because it is perceived that the line needs to be drawn. IFATCA asserts that where gross negligence is involved more often than not, it is evident that a line has been crossed, usually these are explicit acts calculated to cause harm or embarrassment to the ANSP.

Information that is gathered by reporting systems is generally in all cases be used for improving organisational safety. At least this is how IFATCA believes it should be used. Experience would suggest that it is not the case. Using reporting system data to judge Just Culture and to interpret events as gross negligence or not is a misuse of such data. Used in this way it can compromise the trust that is needed for a thriving JC as well as the confidence in disclosing information to the organization.

Determining gross negligence and reckless behaviour is not a function of event reporting. Other mechanisms and processes will be in place within an organization that are formalised and designed within the formal arrangements for the handling of such events. To use the incident reporting mechanism in this way is a gross misuse of a process and to use it in a way that it is neither designed nor suited for.

All previous attempts to assess or draw the line such as the substitution test or definitions of gross negligence and reckless behaviour are, in IFATCA’s experience, irrelevant to Just Culture. Because they are inherently tools to make judgments about an individual, frequently outside the context and reality of the operational environment, they inherently lack objectivity and either are, or will be perceived, as principally concerned with retribution.

Drawing the Line

Determining culpability of any kind also directs attention to the organization that commits the reckless and negligent behaviour: this is often referred to as drawing the line.

i. How to deal with it

Each of these paths of JC will draw upon all that has been gained in building JC – but each path will take a different approach to JC.

In the case where an event takes a path involving the judiciary and ultimately the courts, it is important to appreciate that even the MAs organisation itself will have little influence or control over the events that unfold. In this case, unequivocally – the judiciary will draw the line.

In these cases, the trust between the organisation and its executive and managers and the operational community can be placed in tension. As far as practical working with the organisation can allow for synergies that protect both parties. Whatever the outcome maybe, it is at this time:

ii – Who draws the line?

Where an event occurs that does not follow the judicial path, the question arises who does draw the line? This aspect is one that an MA can develop with its own organisation as they collaborate or work together to realise a Just Culture.

The MA should strive for arrangements where the operational community can have an effective influence on who draws the line. And, moreover, that drawing the line is achieved in a way that reflects the realities of the operational practice of the typical day to day work. Not to draw the line in the context of work as is imagined.

Further considerations towards a mature JC

The significance and importance of reporting systems and investigation: a persistent feature in the guidelines is the part that reporting systems and the way that investigations are conducted. This should come as no surprise. One way of considering this is that by filing a report it is in essence establishing a contract with the organisation that the act of reporting, and sharing experience of working within the system will lead to a change in the safety of the system. To fulfil this requires a different approach and model of safety from those that prevail in ANSPs today.

As organisations develop an understanding of JC and relationships mature, it will be the case that what is once taken for granted about safety for example is seen in a different light. It is inherent in Just Culture that the place that the human has in interpretations of how untoward events manifest themselves may change. There may be no emphasis on the failure of the human but more on the system itself – system failures. What are called human errors are the outcomes of people having to cope with and adapt to conditions forced upon them to perform beyond their ‘text book’ competences; these forces often include commercial or production pressures, unforeseen dynamics or increases in tempo, etc.

This change in approach may therefore call into question the ways that safety is measured in an organisation. Behavioural observation techniques such as NOSS, D2D can be seen to be incompatible with the underlying philosophy of JC. The emphasis needs to be on system behaviour and not human performance. The human works within a system and therefore the context by which to understand the human’s actions can only be seen through a filter of the system. Techniques such as NOSS and D2D explicitly do not do this

Language is all important in terms of JC. This is a matter of the nature of the discourse that your organisation undertakes. Occurrence reports can be written in ways that are not indicative of blame or holding the human culpable – they can be written in with neutralised language. Managers and the operational community can strive together to use neutralised language. The operational community themselves can be the harshest critics of others in the operation. Here, the use of non-punitive language can have a significant impact on the JC discourse as well.

Very few MA’s have influence on organisational disciplinary systems and have no influence on national judicial systems. As an MA it is important to be aware of when you engage in the development of agreements on how to handle these issues.

It is human nature when things go awry for people to distance themselves from the event – to try to keep problems away from the individual themselves. This applies to those inside as well as outside the operational arena: therefore including unit and organisational management and other people who are not directly involved in incidents and accidents but who maybe or who are implicated in some way, such that they will try to reduce anxiety arising from potential harm. This often results in management and other staff not directly involved in the incident or accident, pushing all problems towards the sharp end and away from themselves. For example, pointing at an individual’s competence or performance, or focusing on violations. There is nothing unnatural about this and as Dekker says ‘never underestimate the defence mechanism’.

Conclusions

3.1 Arisen from the discussion.

Recommendation

It is recommended that conference accepts:

4.1. That the current IFATCA policy on Just culture is amended by the inclusions of the guidance material that is presented in this paper and found in section 2 in its entirety.

4.2. It is recommended that the EB designates EVP-P to form a working group to review the JC elements in all of the IFATCA policy.

4.3. It is recommended that PC and EVP-P in conjunction with the Regional EVP’s develop and create education for the MAs as well as some form of training that allows a pool of knowledge to be created within the IFATCA Regions.

4.4. It is recommended that the IFATCA policy on NOSS is inconsistent with the IFATCA ideals for Just Culture. Therefore, it should be removed from the IFATCA policy.

References

Amalberti, R. (2001). The paradoxes of almost totally safe transportation systems. Safety Science, 37, 109- 126.

Dekker S.W.A. (2007). Just Culture, Balancing Safety and Accountability. Aldershot, UK: Ashgate