DISCLAIMER

The draft recommendations contained herein were preliminary drafts submitted for discussion purposes only and do not constitute final determinations. They have been subject to modification, substitution, or rejection and may not reflect the adopted positions of IFATCA. For the most current version of all official policies, including the identification of any documents that have been superseded or amended, please refer to the IFATCA Technical and Professional Manual (TPM).

55TH ANNUAL CONFERENCE, Las Vegas, USA, 14-18 March 2016WP No. 302Ageing Air Traffic Controllers: Consequences on Job PerformancePresented by PLC |

Summary

The aim of this paper is to summarise the potential effects of ageing on air traffic controllers cognitive functioning and subsequent consequences on job performance, safety and efficiency. An important question is under what conditions are knowledge and experience likely to mitigate potential age declines for domain-relevant tasks since older air traffic controllers may be able to use highly practiced skills or draw upon compensatory strategies for such tasks. There are well-documented findings indicating a decline in fluid intellectual abilities over a life cycle. Despite controversy existing about the exact age when the decline peaks, the typical research finding is that one ́s maximum capacity in essential functions declines from the early 20s (Schaie,1996). This is the origin of the theory, there is an emerging view towards maintaining ability and continued competence rather than focussing on “age” per se. Mitigation strategies to cope with those cognitive skills that are likely to decline, are discussed in this paper.

Introduction

1.1. This paper was requested by the Netherlands at the 2015 IFATCA Conference in Sofia (Bulgaria).

1.2. As Air Traffic Control (ATC) is becoming increasingly complex and dynamic, factors related to the human side of the Air Traffic Management (ATM) system are becoming more critical. In this context, concerns are raised over the ageing of the ATC workforce of many countries and the potential effects it has on cognitive functioning, with subsequent consequences on job performance, safety and efficiency.

1.3. It should be emphasised that ageing is a natural process involving multiple factors. It can not only be related to deterioration and decline since a number of mental and social abilities can undergo a positive change with increasing age. Ageing Air Traffic Control Officers (ATCOs) can draw upon experience and apply their resources in a more efficient way to compensation for a potential reduced ability to meet job demands.

1.4. The subject has been touched and presented at the IFATCA Conference, in Punta Cana 2010, where policy was introduced.

Discussion

2.1. Age-related effects on cognition

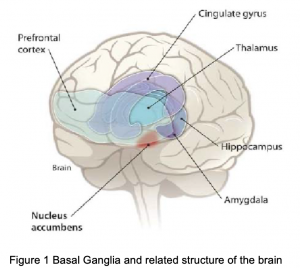

2.1.1. Cognitive ageing is complex and it occurs in tandem with the physical degradation of the brain structure. Shrinkage and death of neurons and reduction in the number of synaptic and functional synapses contribute to variances in the thalamus, (which is involved in sight, hearing and sleep-wake cycle), in the nucleus accumbens (which plays a major role in mood regulation) and in the hippocampus, critical site for consolidation of short-term to long-term memory (Fjell A et al, 2010). See figure 1.

2.1.2. Little age-related decline has been reported in some mental functions such as vocabulary, some numerical skills and general knowledge, but some mental capabilities such as certain aspects of memory, executive functions, processing speed, reasoning and multitasking have been reported to start declining as early as in the mid twenties (Verhaeghen & Salthoues, 1997).

2.1.3. In relation with memory, it must be said that all types of memory are not equally affected by ageing effects (Rybash, Roodin Santrock, 1991). Memory can be divided into 3 types:

- The sensory store, hardly affected by ageing since it ́s an unconscious process, keeps incoming information for only milliseconds in memory allowing a first quick check of the information.

- Short-term memory, also known as working memory, is responsible for processing incoming information. The dynamics of short-term memory, particularly the speed of working memory, are to a certain extent affected by age (Salthouse, 1994). Reduction in short term memory is especially noticeable for tasks with a high demand on short-term memory such as the division of attention between different tasks (multitasking).

- Long-term memory, performance seems to decline too with age depending on the following 4 factors: the learning strategy, the nature of the memory test, the material to be remembered and individual characteristics of the person remembering (attitudes, interests, health- related factors).

2.1.4. As for spatial reasoning, defined as the ability to mentally manipulate 2- dimensional and 3-dimensional figures, it is known that the processing of spatial information slows down with age (Salthouse, Babcock, Skovroneck, Mitchell & Palmon, 1990). The ability of perspective-taking, mental rotation and abstraction and integration of large scale spatial information slows down with age, especially when abstract components are involved. When the material is concrete and familiar, ageing effects are reduced or even eliminated.

2.1.5. The impact of age in the process of problem solving, described as a set of mental operations and transformations that enable the individual to move from an initial state to a goal state is different, it depends if the domains are familiar or unfamiliar. In unfamiliar domains, older people display a decreased efficiency in problem solving, especially with increased complexity of the problems, while in familiar domains there is hardly any age-related decline recognised because older people develop a high degree of competence in their domain of expertise (Charness, 1985).

2.1.6. There are two overlapping categories of intelligence (Catell, 1971) and the distinction between them is important because the relations of age are quite different for the two forms of cognition:

- Fluid intelligence, the capacity to think logically and most associated with working memory, abstract reasoning, attention and processing of novel information tends to decline with age.

- Crystallized intelligence, the cumulative products of processing from earlier periods of life and the ability to use skills, knowledge and experience. It is required for solving well-known and familiar problems. There ́s no evidence that age-related decline effects it, on the contrary, it does improve with age as experiences expand one ́s knowledge.

2.2. Ageing and Work Performance in ATC

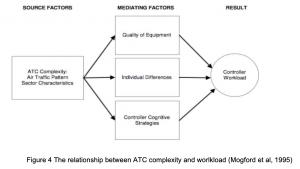

2.2.1. The potential effects of ageing on cognitive functioning and the consequences of these changes on work performance are important considerations associated with the ATC workforce. Age-related cognitive decline is relevant to ATC tasks such as; identified prioritisation analysis, situational awareness, multitasking, planning, execution, thinking ahead, reasoning and timesharing are some of the most relevant cognitive functions for air traffic controllers in their daily tasks.

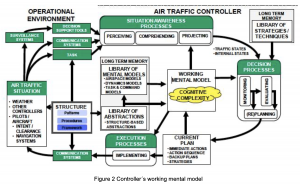

2.2.2. The following working mental model of air traffic controllers’ tasks (Histon J. et al, 2010) Figure 2, supports the generation and maintenance of situation awareness as well as the various decision-making and implementation processes. This working mental model integrates the various sources of information available to the air traffic controller officer (ATCO).

2.2.3. Researchers have speculated about the possible causes of the decline in job performance with age (Becker & Milke, 1998; Salthause, 1994; Tsang & Shaner, 1998; Heil, 1999). Discrepancies have been reported in this literature because of the insufficient empirical data produced concerning the relationship between age and cognitive test performance. Based on this research older ATCOs would be expected to demonstrate lower levels of performance on measures of cognitive ability, especially on tasks that require the greatest amount of fluid intelligence, processing speed, and time-sharing, as early as in their mid 40s. Following Tsang and Shaner ́s study (1998), both expertise and practice can reduce age-related declines in performance while Heil ́s study (1999) failed to demonstrate that experience moderates the relationship between age and basic cognitive processes. Ageing workers may be able to compensate for a reduced physical or mental capacity through acquired job experience and a more efficient utilisation of resources, but this is only possible when job demands remain lower than overall work capacity and when there is a flexibility in job content (Laflamme, 1995).

2.2.4. Recently, Nunes and Kramer (2009) have examined whether high levels of experience serve to reduce age-related decline on basic perceptual, cognitive or motor abilities and if general or specific strategies can be put in place in order to compensate for the impact of aging on complex skills. Domain- relevant abilities included in the study are task-switching ability, visual spatial ability, working memory, processing speed, inductive reasoning, visual spatial processing, breadth of visual attention and measured tasks such as conflict detection, conflict resolution, vectoring and airspace management. Conclusions drawn from the results are that experience seems to moderate the effects of age-related decline only on a subset of the most relevant of cognitive abilities underlying in a complex task performance and that the knowledge older workers use to mitigate the impact of age-related cognitive decrements as task complexity increases.

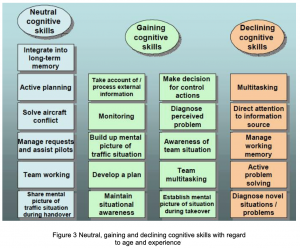

2.2.5. The European project, “Solutions for Human-Automation Partnerships in European ATM” (SHAPE) has identified seven main interacting factors to a better harmonisation between automated support and the controller: Trust, Situation awareness, Teams, Skill sets requirements, Recovery from system failure, Workload and Ageing. As part of this big project, a survey was conducted in the European Civil Aviation Conference Area on the issue of cognitive ageing, expertise and automation. Using the results, key elements of ageing in ATM were identified and split into three areas: cognitive skills likely to decline with ageing, cognitive skills likely to improve because of gained experience and cognitive skills likely to remain unchanged (Figure 3).

2.2.6. Studies conducted so far, on ageing in ATM have investigated abilities that represent only a small subset of those needed to succeed in the real world. Findings do not support the idea that older ATCOs are unable to safely manage the flow of traffic within their units of certification and that some countermeasures and mitigation strategies are required for those skills because they are likely to decline.

2.2.7. Two important goals for futures researches would firstly be to discover why and when both unique and shared age-related effects would start to occur on many cognitive variables and secondly is to explain how increased knowledge might operate to offset the negative consequences of declining cognitive abilities to maintain a high level of performance.

2.2.8. See also PLC paper on Cognitive Processes in Air Traffic Control, Las Vegas, 2016.

2.3. New technologies (Automation)

2.3.1. Acceptance, among those who must ultimately use the tools, is a key element in order to obtain the expected outcome from the implementation of a new ATM system. A number of characteristics of new technology provide a challenge for the ageing worker. New developments render compensating strategies less effective. Many human factors issues associated with its introduction should be addressed for all age groups, for example; trust in automation, skill set changes, new errors forms, changes in teamwork, situational awareness and workload. Information displayed on the screen replaces more and more other sources of data. This concentration of data input on only one channel may easily cause an overload of working memory and lead to problems in the distribution of attention.

2.3.2. Both the content and the way it is delivered should be adapted as much as possible to the target group (Human Machine Interfaces): font size, amount of information displayed, use of colours and contrasts on screen, adjustable light sources, reducing background noise and adjustable auditory information. Involving older ATCOs in the design process will facilitate the transition from old to new systems.

2.3.3. IFATCA policy is:

| Operational controllers shall be involved in the design, development and implementation of new ATM systems (Kathmandu, 2012, WP 87; Sofia 2015, WP159) |

2.3.4. See also PLC paper Review of IFATCA automation policy, Las Vegas, 2016

2.4 Mitigation Strategies

2.4.1. Personal & Career Development (PCD)

2.4.1.1. A career development system is defined by Leibowitz (1987) as an “on-going, organised, planned effort which attempts to achieve a balance between individual needs and organisational requirements.” In line with this definition, PCD should be oriented towards both future business needs (Guidelines for Personal and Career Development Processes, EUROCONTROL, 2000) (potential/motivation/capability) and needs of individuals. The latter will vary due to:

- Age

- Personal situation of the individual

- Qualifications, abilities and skills held by the individual

- Range of past and current work experience

- Personal competencies

- Career and development possibilities

2.4.1.2. A systematic approach to career development within the Air Navigation Service Providers (ANSPs) would be desirable. Reciprocal ATCO-Management transactions might create differential trajectories of further development and action opportunities. Ageing controllers should have the opportunity to find working positions according to their competency. On one hand, flexibility concerning not only the transition between ATC units, but switching from operational positions (from executive to planner) or even from demanding sectors to less demanding ones should be an alternative to air traffic controllers in case they cannot cope with the demand for whatever reason. Sadly, this is not always an option for air traffic controllers in view of recent performance policies at all levels: Global, European, national or air service providers’ policies.

2.4.1.3. IFATCA policy is:

| ANSPs should offer career development plans as medium to long term alternatives to the operational job (Punta Cana 2010, WP161) |

2.4.2. Training

2.4.2.1. Differences in cognitive test performance between older and younger workers have led researchers to question whether those differences were modifiable and if training or re-training could reduce or eliminate age-related declines in cognitive test performance. Baltes et al, (1986) reported that short retraining programs could successfully improve both fluid and crystallized abilities concluding that many ageing professionals have the reserve capacity to improve their level of performance on measures of cognitive ability when offered appropriate training. That is, training could help prevent the decline of cognitive skills. Firstly, regular refresher training could help to avoid ageing decline. Secondly, transition training for the implementation of new equipment should consider the needs of ageing controllers. Thirdly, the issue of ageing should be included in training programs in order to raise self-awareness of possible decline of ageing aspects.

2.4.2.2. IFATCA policy is:

| Training courses for ATCOs regarding the issue of ageing should be made available. (Punta Cana, 2010, WP 161) |

2.4.3. Retirement

2.4.3.1. The objective of this paper is to focus on the interaction of age and experience and the potential decline of cognitive skills and job performance. It is not the objective to focus attention on retirement aspects since it is a very controversial issue that may need to be further developed in a future paper. Official age of retirement (receiving full pension), average effective age at which ATCOs withdraw from labour force, early retirement schedules (providing some age and service requirements are met), reduction in pensions are all hotspots that fall out of the scope of this paper.

2.4.3.2. Nevertheless, researchers conclude that ageing is a complex mixture of factors and a continuing process of functional changes associated with gain and loss of functionality which provides the basis for mental performance. Early retirement age could be an instrument to avoid ATCOs from staying operational when a significant deterioration of cognitive skills is expected. Research into “at what stage does an air traffic controller no longer perform satisfactorily operational” has not yet been concluded.

2.4.3.3. IFATCA policy is:

| IFATCA recommends that for active air traffic controllers the age of retirement should be closer to 50 than 55. (Santiago, 1999, WP155) |

2.4.4. Shift work

2.4.4.1. Many studies have reported a variety of adverse biological, psychological and social effects of shift work including reduced and altered sleep, digestive disorders, cardiovascular problems, endocrine disorders and mental imbalance associated with fatigue (Costa, 1996). Consequences for several aspects of performance have also been documented (Folkard, 1996) suggesting changes in alertness and cognitive efficiency in people whose circadian rhythms are disrupted. Adverse effects have been shown on executive functions, temporal memory, attentional processes, working memory (Harrison and Horne 2000) and cognitive performance (Folkard & Monk, 1979; Winget et al, 1984). Moreover, a cumulative effect of chronic exposure to circadian disruption on cerebral and cognitive function has also been reported (Cho et al, 2000).

2.4.4.2. Ageing is known to be associated with changes in tolerance to shift work, greater occurrence of rhythm disturbance and increased sleep troubles (Härmä & Ilmarinen, 1999). Older shift workers would potentially have more trouble with night-time shifts and/or early morning awakenings and therefore develop lower tolerance to shift work. Measures that mitigate the impact that prolonged exposure to shift work has on cognitive abilities should be considered, including switching to normal day work. Recovery of cognitive function occurs some years after having ceased any form of shift work (Marquié et al, 2014).

2.4.4.3. Some air service providers such as Luchtverkeersleiding Nederland (LVNL) offer to those 55 years or above the possibility of quitting night shifts but providing 10% extra leave to those actually continuing to work at night.

2.4.4.4. IFATCA policy is:

|

ATCOs with an age of 50 years and older shall be entitled to abstain from nightshifts on their request (Punta Cana, 2010, WP 161) |

2.4.4.5. Increasing the number of short breaks during a shift.

2.4.4.6. IFATCA policy is:

| Ageing ATCOs should be entitled to specific break plans, in particular additional short breaks, to assist in their performance with short term memory. (Punta Cana, 2010, WP 161) |

2.4.5. Fitness to work

2.4.5.1. One of the main problems in ageing controllers could be the potential decline in functional capacity of the controller when meeting demands of the job. A “fitness to work assessment” for the ageing ATCO should be more than just a medical assessment but also include an understanding of the physiological changes in ageing and promoting health policies for example on smoking, diet, alcohol consumption and physical exercise. Certainly, appropriate screening for diseases such as hypertension, diabetes and so on becomes more relevant in an ageing controller but there may also be a wish to screen for physiological conditions by assessing the social-well being and stress levels of the individual.

Conclusions

3.1. Ageing is part of a natural process consisting of physiological as well as functional changes concerning all human beings. The potential effects of ageing on cognitive functioning and the consequences of these changes on job performance are important considerations associated with the ageing of ATCOs. A by product of age can be experience.

3.2. According to scientific literature there are a number of cognitive skills that deteriorate with age such as multitasking, direct attention to information source, manage of work memory, active problem solving and diagnosis novel situations and/or problems.

3.3. On the other hand, some cognitive skills have been reported to improve: taking account of and processing external information, monitoring, building up mental pictures, developing action plans, maintaining situational awareness, decision- making for control actions, diagnosis of perceived problems, awareness of team situation.

3.4. Although discrepancies have been reported in literature, considering insufficient empirical data produced, concerning the relationship between age and cognitive test performance. It is commonly accepted that the decline in previous mentioned cognitive abilities is of utmost importance to a successful job performance (Nickels et al, 1995). Controversy about the age at which cognitive decline begins is also present.

3.5. From a theoretical point of view, experience appears to moderate the effects of age-related decline on only a subset of the most relevant of cognitive abilities that underlie complex task performance. Researches support the idea that experience would off-set potential age-related decrements on those cognitive abilities that are most directly related to ATC through acquired job experience and a more efficient utilization of resources but this would only be possible when job demands remain lower than overall work capacity.

3.6. The introduction of sophisticated computerised air traffic control equipment may imply a challenge for ageing ATCOs. In addition, technological changes could bear the danger of outdating expertise. Therefore, the need exists for the development of tools and guidance material supporting older controllers transitioning successfully in doing their job with a new automated system.

3.7. Mitigation strategies to cope with the effect of declining cognitive abilities as a result of ageing shall be in place. Examples of mitigation strategies is a career development system allowing ATCOs to find working positions according to their competency, training programs that consider the needs of ageing controllers, retirement policies, reduction in the number of night shifts, increase the number of short breaks at work, effective fitness to work assessments.

Recommendations

4.1. It is recommended that this paper is accepted as information.

References

Bruce J.A., Waldman D.A., 1990, An Examination of Age and Cognitive Test Performance, Journal of Applied Psychology, 75:1, pg 43

Heil M.C., 1999, Air Traffic Control Specialist Age and Cognitive Test Performance, U.S. Department of Transportation/FAA/AM-99/23

Heil M.C., 1999, An Investigation of the Relationship between Chronological Age and Indicators of Job Performance for Incumbent Air Traffic Control Specialists, U.S. Department of Transportation/FAA/AM-99/18

Histon J., Hansman J., Gottlieb B., Kleinwaks H., Yenson S. et al., 2002, Structural Considerations and cognitive complexity in air traffic control, 21st Digital Avionics Systems Conference, Irvine, US. pp 1C2-13 vol.1

IFATCA, Technical and Professional Manual 2015

Marquié JC., Tucker P., Folkard S. et al, 2013,Chronic effects of shift work on cognition:findings from a VISAT longitudinal study, Occup Environ Med., 10.1136

Morrow D.G., Menard W.E., Stine-Morrow E.A, 2001, The Influence of Expertise and Task Factors on age Differences in Pilot Communication, American Psychological Association, Inc., Psychology and Aging, Vol. 16, No 1, 31-46

Nickels, B.J. et al, 1995, Separation and Control Hiring Assessment, Federal Aviation Administration Office of Personnel.

Nunes A., Kramer A.F., 2009, Experience-Based Mitigation of Age-related Performance Declines: Evidence from Air Traffic Control, American Psychological Association, J.Exp Psychol Appl. 15(1): 12-24.

Ribas V.R. et al., 2010, Air Traffic Control activity increases attention capacity in air traffic controllers, Dement Neuropsychol, 4(3): 250-255

Ross, D., 2010, Ageing and Work: an overview, Occupational Medicine; 60:169-171

Rouch I., Wild P., Ansiau D et Marquié J.C., 2005, Shiftwork experience, age and cognitive performance, Ergonomics, 48:10, 1282-1293.

Schroeder D.H., Salthouse T.A, 2003, Age-related effects on cognition between 20 and 50 years of age, Elsevier Ltd., Personality and Individual Differences 36, 393-404

Timothy A., Salthouse, PhD, 2009, When does age-related cognitive decline begin?, NIH- Neurobiol Aging, 30(4):507-514