DISCLAIMER

The draft recommendations contained herein were preliminary drafts submitted for discussion purposes only and do not constitute final determinations. They have been subject to modification, substitution, or rejection and may not reflect the adopted positions of IFATCA. For the most current version of all official policies, including the identification of any documents that have been superseded or amended, please refer to the IFATCA Technical and Professional Manual (TPM).

52ND ANNUAL CONFERENCE, Bali, Indonesia, 24-28 April 2013WP No. 166The Fountain of WellbeingPresented by Trinidad & Tobago |

| IMPORTANT EDITORIAL NOTE: This working paper includes a large number of appendices that could not easily be reproduced here in WIKIFATCA. To consult these appendices, please consult the original working paper in PDF format by clicking HERE. The working paper can also be found on the IFATCA website (https://www.ifatca.org), under IFATCA-NET, Conference Archives. |

Introduction

1.1. The origins of the wet elixir of wellbeing and a dry summary

The man that has moved mountains started by moving small stones – Confucius.

1.2. The origins of wellbeing

Spanish explorer Juan Ponce de Leon (Douglas T Peck, 1998, Anatomy of an Historical Fantasy: the Ponce de Léon-Fountain of Youth Legend, Revista de Historia de America, # 123 Jan – Dec 1998, 63-87, Pan American Institute of History and Geography, https://www.jstor.org/stable/20139991 (accessed 26th February 2013)) was never interested in the quest for a fountain of youth . He did not believe that such a thing existed. And the Neoindians whom he met on his travels in the so-called New World also shared his sentiments. The notion that he was looking for a water source to revive his prowess was a myth that bordered on absurdity since he had fathered 21 children and had taken along his mistress on his voyage to the Caribbean. Tales of a magical water-based elixir has always appealed to the greater part of mankind in the face of common sense and logic. The latter has prevailed, however. In this paper, the fountain is no more than a symbolism of our attempts at finding balance between work and play so as to define and improve our wellbeing.

1.3. An overview of the paper

Increasing attention is placed on wellbeing and work-life balance not only because we spend more and more time at work but also because it is a predictor of individual and organizational performance. The domain of Air Traffic Control is not without exception. From an organizational perspective, the theme of this year’s conference <<Satisfied controller equals safe sky>> is a potential truism with important implications. What does this mean? If controllers are satisfied, wellbeing will increase which will result in better performance and in turn, safer skies. ATC is a service based industry (Christian Gronroos & Katri Ojasalo, 2004, Service productivity towards a conceptualization of the transformation of inputs into economic results in services, JOURNAL of BUSINESS RESEARCH (5703) 2002) so if wellbeing increases, controllers will produce better service-related goods of communication which will yield better performance and in turn, safer skies. In this paper, job satisfaction is a part of wellbeing as the latter is a more – aggregate concept (P Schulte & H Vanio, 2010, Wellbeing at Work – Overview and perspective, PubMed https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20686738).

1.4. However, no known definition of wellbeing exists in ATC. We do not have a fountain of wellbeing so we do not know what really makes controllers satisfied. Is it the thrill of ATC, specific working conditions, a means of income, the ATCO’s disposition or a combination of features? We need to verify the elements of wellbeing that make ATCOs satisfied so that we can better assess the link to safety performance. To help us, we are going to look at the evidence of 2 studies: a global study of controllers and a comparative study of employees from around the world. These studies will not only give credence to our linkage of satisfaction and performance safety but they will also justify the following: – (i) that wellbeing is a more-aggregate concept than job satisfaction, (ii) the need for a definition of wellbeing in the context of ATC and (ii) amending the Section of Working Conditions in IFATCA’s Technical and Professional Manual to represent the holistic approach to wellbeing.

1.5.We begin with viewpoints and allusions of wellbeing from the World Health Organization and experts in ergonomics, behavioral economics, organizational psychology and occupational therapy.

Discussion

2.1. Wellbeing has a timeline and even tweets of theory but – does it have friends in ATC?

Instead of thinking outside the box, get rid of the box – Deepak Chopra

Chronological definition of wellbeing

Until the 21st century, the word wellbeing has always been obscured by the drapes of ambiguity. No clear and concise definition existed but it was often alluded to. Without forewarning, this word and its associate, wellness, flooded our media sources. The mystical fountain of youth had been reworked into something tangible that organizations could relate to. But the meanings were difficult to apply in the contextual framework of jobs and the term job satisfaction was a suitable replacement. Now that the experts have a more comprehensive understanding of wellbeing, the term job satisfaction is now exiting through the back door to make way for the new terminology work-life balance (Linda Duxbury et Chris Higgins, 2001, Work-Life Balance in the New Millennium: Where are we? Where do we need to go? Réseaux canadiens de recherche en politiques publiques, 3-5). Perhaps the owners of the various wellness retreat and spas in Bali might be able to enlighten us further. In the meantime, we consider various perspectives of this concept throughout time.

2.2 In the preamble to its constitution of 1946, the World Health Organization (Preamble to the Constitution of the World Health Organization, adopted by the International Health Conference, New York, 19-22 June, 1946; signed on 22 July 1946 by the representatives of 61 States (Official Records of the World Health Organization, no. 2, p. 100) and entered into force on 7 April 1948) identified different elements of wellbeing in its definition of health. Then in 1976, a behavioral economist (Daniel Kahneman et al , 1999, Wellbeing : the Foundations of Hedonic Psychology, Russell Sage Foundation, ISBN: 0-87154-423-7 (paper) 392-412) embarked upon a study to show that happiness at work is related to an individual’s overall state of happiness or eudemonia. Slowly the drapes of ambiguity began to dry rot and crumble as the understanding of the role of wellbeing in the workplace progressed. In 1990, an organizational psychologist (William A Kahn, 1990, Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work, ACAD MANAGE J Dec 1 1990 Vol 33 # 4 692-724) used a model of engagement to show that a worker will feel engaged in her job, if she has the necessary psychological resources. As a result, she will find that her job is meaningful. She will also feel free and safe to express herself without reprisal and to grow or develop her career. In 2011, Professor Martin Seligman (Martin E P Seligman, April 2011, What is Wellbeing? University of Pennsylvania) explains that wellbeing is a state of authentic happiness which comprises 3 elements: positive emotion, engagement and meaning. Of engagement, he explains that it characterizes a state of flow where you are so absorbed or engaged in your work activity that time seems to stop. Do you think that it is possible to experience this flow in ATC?

2.3 Of course, the economists had something to say. They wanted the world to know that measures of job satisfaction should not be restricted to gender, years of work experience and wages (Andrew E Clark, 1998, Measures of Job Satisfaction, what makes a good job – Evidence from OECD countries, OECD, 14th August 1998). That productivity will increase if wellbeing increases (Kari Rissa, 2007, The Druvan Model, Wellbeing Creates Productivity, PunaMusta Isalmi, ISBN: 978-951-810-340-3 (PDF)). And there is a complementary link between organizational success and worker dignity (Randy Hodson & Vincent J Roscigno, 2004, Organizational success and worker dignity: complementary or contradictory, AJS, Vol 110 #3 672-708). These are but a few examples of what the definition included. To date, there is no known application of wellbeing to ATC. Which of these definitions do you think will make good starting points?

2.4 We can write the definitions down, put them in a hat, choose one and vote on it. A better alternative will be to find out why workplace wellbeing is such a growing issue and we look for the matching circumstances in ATC. Then we vote on a working definition. Let us hope that someone is present at the meeting with a hat and scissors.

2.5 The re-emergence of the symbolic fountain of wellbeing in the 21st century

From a national study done in 2006 by the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development, United Kingdom, a symbolic fountain of wellbeing was recommended as our panacea for the pandemic of worker absenteeism and benefit claims. They also found that employees go in to their jobs but come out with chronic, psychosomatic illnesses related to stress, fatigue and social dysfunctional problems that collectively took a huge chunk of their national GDP:

- Absenteeism costed organizations £600 annually per member of staff (CIPD survey)

- Incapacity Benefit claims increased from 0.7 million in the 1970s to 2.7 million in 2006 (Department of Work and Pensions (DWP))

- Employee problems of mental health increased from 25% in the mid-1990s to 40% in recent times

- The annual estimated cost of stress is £3.8 billion according to the Health and Safety Executive (HSE)

- The first prize of contention goes to the increasing percentage of the aging workforce and the need to work longer so as to accumulate ample retirement funds

2.6 Perhaps the most classical case in favor of re-establishing the symbolic fountain of wellbeing was the case of the Renault worker who fell from a third story passerelle in 2006 (https://www.leparisien.fr/Economie, Suicides chez Renault : <<On ne peut pas broyer des gens pour des bénéfices>>, publié le 19 10 2009). At first, it was stated that he fell, followed by the claim that he was negligent. When compelled to admit that it was suicide, the company produced a medical report as proof of the worker having family and personal problems. Undaunted by the paternalism of management and the denunciations of the company’s lawyer, the widower insisted that her husband loved his job but she had seen him progressed from a jovial man into an emotionally overwhelmed stranger and she stood her ground that the organization was at fault.

2.7 The Labor syndicate arranged to send in a team of analysts who had to persist that they wanted to meet with the employees (https://blogs.senat.fr/ Le Mal Etre au Travail, Mer 7 avril, 2010, Visite du Technocentre du Renault à Guyancourt le jeudi 25 mars 2010). They also met with the director responsible for the wellbeing of the employees and he reassured them of the implementation of a plan of action that was worthy of a national award. He explained the latest strategy of reduced work hours, increased local HR management, open forum, better work organization, stress management training and even a psychologist that employees can freely consult with. The analysts went ahead with their psychometrics and much to their chagrin they found that a larger proportion of management was unsuitable for the role, the union-management relationship was very poor and the workers were stressed because of unreasonable deadlines and cost-cutting measures.

2.8 In 2010 the court ruled that the worker developed anxiety-related depression due to his dissatisfaction with certain working conditions (S. A. Renault contre Sylvie T., Cour d’Appel de Versailles, 10/00954). It affected his psychological balance and had progressed to the point where he saw death as the only solution. What a sobering wake-up call! Do any of the circumstances above match what is currently happening in some units? Note that the worker loved his job, but he was dissatisfied with certain working conditions. He was so faithful to the company that he did not want to leave even though he was unhappy with several aspects.

2.9 The role of workplace wellbeing can never be overestimated (Daniel Kahneman and Angus Deaton, 2010, High income improves evaluation of life but not emotional wellbeing, Center for Health and Wellbeing, Princeton University, PNAS). An organization with a good state of wellbeing will have workers with good individual states of wellbeing and vice versa. It is about balancing the aims of the organization with that of the employee to produce better outcomes for both parties. Wellbeing is also a subjective constraint (James B Avey et al, 2010, Impact of positive psychological capital on employee wellbeing over time, Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 15:1 (19)). Thus the easiest place to derive a workable definition in the context of ATC is at a global level where one standard can be developed. In turn this standard must be flexible enough to accommodate the subjection of subunits and that of individuals. To reiterate, we have discussed some basic concepts of wellbeing and a context of circumstances. Now we need to place some words together and voila! No, we need to support our claims with corroborative evidence before we can construct our fountain of wellbeing in ATC. Let us now consider our first study which shows that a significant relationship exists between organizational structure and our work environment/culture.

2.10 An analysis of wellbeing among ATCOs

2.11 The value of doing a feasibility study

2.12 There is a reason why the Tower of Pisa leans. Since we do not want to construct a leaning fountain of wellbeing, we are going to do what the 12th century engineers thought was too costly – conduct a feasibility study.

2.13 Imagine that you wished to build a real fountain in your backyard. You will carefully consider several factors before deciding that this is a project you want to undertake. One of the first things that you will consider is if you really need a fountain. Is it a preference of yours or a loved one? This is where contextual circumstances apply. You might not like fountains but your loved one does so yes, the fountain is a good idea. Another factor you will consider is if you can afford to set up a fountain. This will determine the length of time taken to set it up; whether it is a costly long term goal that must be done in stages. You will also consult the internet and with your loved one, friends and anyone who has an opinion to give on fountains. This is because you would like to decide upon the type and the corresponding materials that you will buy for your fountain. That is the basis of your feasibility study.

2.14 To construct our symbolic fountain of wellbeing or to come up with a comprehensive definition we follow a similar procedure.

We attempt to answer the following questions:

- What basic concept of wellbeing can we use as a foundation for ATC?

- What is the overall aim of our profession and what direction is it heading in over the next 10 years?

- Is the organization in need of a global standard for wellbeing?

2.15 Gathering corroborative evidence via a study on ATCOs

We use the questions above to guide us so as to prevent our individual biases from clouding our judgments about issues at the organizational level. In answer to the first question, the most recent concept of wellbeing by Professor Seligman will be used as the starting point or foundation for our fountain. He explained that wellbeing is comprised of 3 elements of authentic happiness: positive emotion, engagement and meaning. Using the theme of the conference, we would like to know what elements of workplace wellbeing bring satisfaction to ATCOs.

2.16 In November 2012, an inventory of wellbeing for ATC was placed on the internet. Past and present controllers as well as assistants were invited to fill this anonymous inventory of 57 items that had a reliability coefficient of 0.7871 (see Appendix I). At the time of analysis, there were 126 respondents with an average of 15 years of experience. 75% of the respondents came from the L, E & U region according to the ICAO standard of country identification.

2.17 The inventory was made on the assumption that job satisfaction is a part of wellbeing which is a more aggregate concept. It could be likened to taking a vacation. On my vacation, I do several things. I spend a day walking around the city, another day visiting museums and another day at the beach. My vacation refreshed and revived my whole being as each day of activity brought me satisfaction. I enjoyed the day at the museums but after 2 hours of looking at paintings, the activity became boring. Yet I still enjoyed my vacation. Job satisfaction is likened to those activities that were part of my vacation. Remember the Renault employee? He loved his job but he was not satisfied with some of the working conditions. In another example, my job could be satisfying because it allows me to pay my bills and satisfy my preferences but that does not mean that I like it. This dissonance impacts negatively upon my wellbeing.

2.18 The second assumption is that elements of organizational structure (OS) are linked to wellbeing (W) and that elements of the social matrix (SM) are also linked to wellbeing (W). This assumption is based upon the third reasoning that an organization has a (1) structure as well as (2) an environment and a culture which impacts upon our wellbeing. The items came from these 2 dimensions, to determine the extent to which ATCOs are satisfied on a global level.

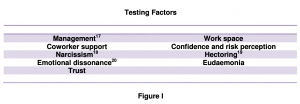

A total of 9 factors were tested:

2.19 The respondents had to answer 5 types of questions based on the Likert scale concept of Yes/No, Agree-Disagree, Easy-Difficult, Frequently-Never, Confident-not confident, Likely-unlikely. They also had to choose items from a miniature personality inventory and rate several items that they thought were important for their satisfaction in ATC. What did the descriptive statistics reveal? What elements of wellbeing bring satisfaction to ATCOs? (See Appendix IIa-k)

2.20 Structural Equation Modelling or SEM analysis (Christina Werner and Prof. Dr. Karin Schermelleh-Engel, 2009, Structural Equation Modelling, Advantages, Challenges and Problems, Goethe University, Frankfurt) is useful for measuring the relationships between variables. We use STATA 12© to help us analyze whether the organization is in need of a global standard for wellbeing by comparing the relationships between W and OS and between W and SM.

2.21 Elements of organizational structure (Gerard Lécrivain, https://www.managmarket.com/managementdesorg/dossier3-la-dynamique-des-structures.pdf) will refer to the organization of authority, the definition of roles, teams, outline of strategies, the flow of power in the decision- making and the flow of information. Examples of elements of organizational structure include the strength of the union-management relationship and the management style.

2.22 The workplace could be likened to a nation with an environment and a culture (Gareth Morgan, 2006, Images of Organization, Sage Publications, ISBN: 1-4129-3979-8 (PBK) 115-128) of its own. Because ATC is a service-based industry of teams/groups/shift systems, the environment and the culture are mainly social. We refer to it as our social matrix. Elements of social environment and culture include work spaces, coworker interaction and support, the behavior of managers and the effects of the job upon our psychocognitive processes and our self-growth.

2.23 Selecting the best test variables by Confirmatory Factor Analysis or CFA, we conduct a SEM analysis to determine the relationship between organizational structure, the social matrix and satisfaction. What did the SEM analysis reveal? At the 95% confidence limit, the covariance between OS and SM is significant and the covariance between SM and W is also significant.

Relationship Path for ATCO Wellbeing

Organizational Structure ⇒ Social Matrix ⇒ Wellbeing

2.24 The analysis also revealed that the covariance between W and OS is not significant even at a 90% level confidence limit. The value of the coefficient, β is negligible – 0.002 (see Figure III). We will interpret this in the Discussion.

2.25 Irrespective of the interpretation, the βeta coefficient for the organizational structure is a cause for concern. We compare the estimations of a second dataset to validate this finding.

2.26 A comparative study using a Worker Ethnography (WE) We use a Worker Ethnography data set obtained in January 2013 with permission from Professor Randy Hodson, Sociology Department, Ohio State University. Ethnography refers to the study of culture so this study focused on the structure and culture of organizations. 217 groups of employees from 9 professions (Professional, manager, clerical, sales, skilled, assembly, unskilled, service and farm) participated in a worker ethnography study from 19 countries (Australia, Britain, Canada, China, Colombia, France, Hungary, India, Israel, Japan, Norway, Philippines, Scotland, South Africa, Sweden, Taiwan, U.S, Zambia) for specific periods over a period of 72 years, 1929-2001. A group consisted of 1-3647 employees. The total number of employees who participated in the study were 38 682. These groups participated in the study from at least 1month-40 years. Variables from the WE dataset were selected on the basis of similarity with the testing variables from the ATC dataset. (See Appendix IIIa-g)

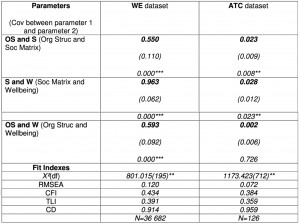

Comparison of WE dataset and ATC dataset

Cov – covariance, β – beta coefficient, N – number, (standard error), **p<0.05, ***p<0.001, X2(df) – chi2, RMSEA – root mean square error of approximation, CFI – comparative Fit Index, TLI – Tucker Lewis Index, CD – coefficient of determination

2.27 Parlez-vous français? Or in english : interpreting the results

If the last section was perplexing, do not worry. The language of data analysis is confusing just as ATC phraseology. Look at the table closely. We see 2 sets of results. Since we are talking about fountains, think of the results as water that will flow from fountain A – the ethnography dataset and the water that will flow from fountain B – our dataset.

2.28 We are interested in the pressure, flow speed and height that the water reaches to determine the fountain flow of our water. We check the relationships between these 3 dimensions so as to have an idea of what adjustments we may need to make to get a vibrant fountain. Our proposed fountain – fountain B is smaller than the prospective fountain A. We observe this from the sizes of the datasets, N.

2.29 We expect our measurements for the relationships between our parameters: pressure, flow speed and height of the water for B to be less than for the water of A. In the table our parameters are organizational structure (OS), social matrix (SM) and wellbeing (W). The covariances are the relationships between 2 parameters. We measure 3 covariances or the relationships between the parameters: OS and SM, SM and W and between OS and W. Each of the Fit Indexes (FI) tells us whether the prospective fountains are good models in just the same manner as examining a technical drawing of the dimensions of the prospective real fountains. Simply put, the lower the first 2 values of our FI are, the better the model and the higher our last 3 values are, the better the model.

2.30 We use pressure gauges to measure our flow mechanics of our prospective fountains. In the table our gauge measurements are the Beta coefficients and the P values or probability values tell us whether these measurements are significant at a statistical limit; in this analysis the measurements are done at a confidence limit (CL) of 95%. The analysis shows that the relationship between OS and SM is significant for both of the prospective fountains as well as the relationship between SM and W. Increasing the organizational structure will result in improvements in the social matrix and a subsequent increase in wellbeing.

2.31 The table also shows a discrepancy. Have you seen it as yet? The relationship between OS and W is negligible (β = 0.002) and insignificant (P> |z| = 0.726) compared to the values for prospective fountain A (β = 0.593, P > |z| = 0.000). The relationship between OS and W is not even significant at the 90% CL. Yet logic tells us that the measurements for this relationship in our dataset should mimic the measurements of the same relationship in the comparative dataset given the trend of results. What could account for the negligible effect of the organizational structure upon wellbeing in ATC? (Jacobus W Pienaar, 2011, What lurks beneath leadership ineffectiveness? A theoretical overview, Dept of Ind Psych, South Africa, African Journal of Business Management, Vol 5(26) 10629-10633)

2.32 There are 4 possibilities which will give the same outcome. The organizational structure in ATC is in a porous state. Too much focus on the technical aspect and not enough on the human factors has made the structure porous. Any attempts at dealing with human factor issues seem to fall through the cracks and spaces. The second possibility is that the structure lacks proper configuration so that the effects of good intentions are not far reaching. The third approach is that the framework of objectives is arbitrary because there is no established policy for the structure and other organizational issues. The fourth interpretation is the state of discord and micromanagement within the management hierarchy.

2.33 At least one of those interpretations will have undesirable effects. Whichever interpretation is correct, organizational disorder (OD) is present in ATC (Lynn Godkin and Seth Allcorn, 2009, Dependent Narcissism, Organizational Learning and Human Resource Development, Human Resource Development Review, Sage Pubs, 8(4) 484-505). These situations are characteristic of administrations with uneven distribution of roles and unsuitable management personnel who either lack the expertise or have self- glorifying ambitions. The social matrix in ATC seems to buffer the deficiencies of organizational structure. Supervising ATCOs and other responsible employees in the social matrices take charge of their groups and give the needed attention to the social assets and it is this activity that generates wellbeing in ATC.

Conclusions

3.1 We need a fountain, with reinforcements:

Constant dripping hollows out a stone – Lucretius.

3.2 A study of 140 controllers and assistants reveals that ATCO wellbeing is generated from a social matrix and not from the organizational structure. A comparative study shows that an efficient organizational structure will provide elements that benefit wellbeing. However no clear definition of wellbeing is present in Air Traffic Control. This definition will act as a standard like the symbolic fountain of youth which represents the elements that provide satisfaction and results in positive action, engagement and meaning for Controllers. Only then, can we truly say that ATCOs are satisfied. They are authentically happy. Their level of wellbeing is such that it has an impact upon safety performance and we can test the relationship between wellbeing and safety performance to verify our claim. Until we reach that point, we can only wonder what it would be like to have a fountain of wellbeing.

Recommendations

4.1 This paper be accepted as Information material.

4.2 The topic of ATCO Wellbeing be considered for future PLC review.

References

Douglas T Peck, 1998, Anatomy of an Historical Fantasy: the Ponce de Léon-Fountain of Youth Legend, Revista de Historia de America, # 123 Jan – Dec 1998, 63-87, Pan American Institute of History and Geography, https://www.jstor.org/stable/20139991 (accessed 26th February 2013).

Christian Gronroos & Katri Ojasalo, 2004, Service productivity towards a conceptualization of the transformation of inputs into economic results in services, JOURNAL of BUSINESS RESEARCH (5703) 2002.

P Schulte & H Vanio, 2010, Wellbeing at Work – Overview and perspective, PubMed https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20686738

Linda Duxbury et Chris Higgins, 2001, Work-Life Balance in the New Millennium: Where are we? Where do we need to go? Réseaux canadiens de recherche en politiques publiques, 3- 5.

Preamble to the Constitution of the World Health Organization, Preamble to the Constitution of the World Health Organization as adopted by the International Health Conference, New York, 19-22 June, 1946; signed on 22 July 1946 by the representatives of 61 States (Official Records of the World Health Organization, no. 2, p. 100) and entered into force on 7 April 1948.

Daniel Kahneman et al , 1999, Wellbeing : the Foundations of Hedonic Psychology, Russell Sage Foundation, ISBN: 0-87154-423-7 (paper) 392-412.

William A Kahn, 1990, Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work, ACAD MANAGE J Dec 1 1990 Vol 33 # 4 692-724.

Martin E P Seligman, April 2011, What is Wellbeing? University of Pennsylvania.

Andrew E Clark, 1998, Measures of Job Satisfaction, what makes a good job – Evidence from OECD countries, OECD, 14th August 1998.

Kari Rissa, 2007, The Druvan Model, Wellbeing Creates Productivity, PunaMusta Isalmi, ISBN: 978-951-810-340-3 (PDF).

Randy Hodson & Vincent J Roscigno, 2004, Organizational success and worker dignity: complementary or contradictory, AJS, Vol 110 #3 672-708.

https://www.cipd.co.uk/NR/rdonlyres/DCCE94D7-781A-485A-A702-6DAAB5EA7B27/0/whthapwbwrk.pdf (Absence Management Survey Report, October 2012).

https://www.leparisien.fr/Economie, Suicides chez Renault : <<On ne peut pas broyer des gens pour des bénéfices>>, publié le 19 10 2009.

https://blogs.senat.fr/ Le Mal Etre au Travail, Mer 7 avril, 2010, Visite du Technocentre du Renault à Guyancourt le jeudi 25 mars 2010.

S. A. Renault contre Sylvie T., Cour d’Appel de Versailles, 10/00954.

James B Avey et al, 2010, Impact of positive psychological capital on employee wellbeing over time, Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 15:1 (19).

Robert Hogan et al, 1994, What we know about Leadership: Effectiveness and Personality, American Psychological Association.

Arijit Chatterjee and Donald C Hambrick, 2007, It’s all about me: Narcissistic Chief Executive Officers and their Effects on Company Strategy and Performance, Pennsylvania State University.

Stale Einarsen et al, 2011, Bullying and harassment in the workplace: Developments in Research, Theory and Practice, Taylor and Francis Group: Florida ISBN-13: 978-1-4398- 0490-2 (Ebook-PDF) 228-231.

K A Lewig and M F Dollard, 2003, Emotional dissonance, emotional exhaustion and job satisfaction in call-center workers, European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 12 (4) 366-392.

Christina Werner and Prof. Dr. Karin Schermelleh-Engel, 2009, Structural Equation Modelling, Advantages, Challenges and Problems, Goethe University, Frankfurt.

Gerard Lécrivain, https://www.managmarket.com/managementdesorg/dossier3-la-dynamique-des-structures.pdf

Gareth Morgan, 2006, Images of Organization, Sage Publications, ISBN: 1-4129-3979-8 (PBK) 115-128.

Jacobus W Pienaar, 2011, What lurks beneath leadership ineffectiveness? A theoretical overview, Dept of Ind Psych, South Africa, African Journal of Business Management, Vol 5(26) 10629-10633.

Lynn Godkin and Seth Allcorn, 2009, Dependent Narcissism, Organizational Learning and Human Resource Development, Human Resource Development Review, Sage Pubs, 8(4) 484-505.

Cliodhna Mackensie et al, 2010, Dysfunctional behavior in organizations: Can HRD reduce the impact of dysfunctional organizational behavior – a review and conceptual model, UFHRD.