48TH ANNUAL CONFERENCE, Dubrovnik, Croatia, 20-24 April 2009WP No. 163Review of Retirement PolicyPresented by PLC |

Summary

This paper reviews current IFATCA policy regarding retirement, and its applicability in a changing world. It argues the points for and against special treatment to ATCOs, whilst highlighting financial constraints and current trends in retirement around the world. It also discusses staff shortage issues and attempts to address possible methods for preparation towards retirement.

Introduction

1.1 It was decided during the Annual Conference in Arusha, Tanzania 2008, that IFATCA policy regarding retirement should be revisited.

1.2 This was thought to be topical as some MAs are facing retirement age challenges, and as IFALPA recommended the retirement age of pilots to be raised from 60 to 65.

1.3 IFATCA policy has not been revised since its introduction during the annual conference in Ottawa in 1994 and its amendment in Santiago 1999.

Discussion

2.1 IFATCA policy currently states:

| 5. POLICY RELATING TO RETIREMENT AND PENSION

WC.5.1. RETIREMENT IFATCA POLICY is that: “IFATCA recommends that for active air traffic controllers the age of retirement should be closer to 50 than 55.” “In view of the peculiarity and uniqueness of the profession of Air Traffic Control, and in the interest of air safety, air traffic controllers should be awarded retirement at an earlier age than that of the national retirement age. The retirement age for air traffic controllers should be determined by negotiations at the national level, taking into consideration the physical and psychological demands and the occupational stress the profession involves. Air Traffic Controller retirement legislation must be accompanied by an adequate superannuation scheme which enables the controller to receive pension benefits as if service had continued to national retirement age.” WC.5.2. EARLY RETIREMENT IFATCA POLICY is that: “There should be a possibility to cease from active control before Controller retirement age. Air traffic controllers leaving active control, but staying in employ within the ATC environment should keep their controller retirement privilege.” WC.5.3. EXTENDED DUTY IFATCA POLICY is that: “Individual air traffic controllers who wish to remain in active duty, once they have met the conditions to retire, should be allowed to do so provided they meet all medical and proficiency requirements.” |

2.2 This policy was mainly created following the “Meeting of Experts on Problems Concerning Air Traffic Controllers” at the ILO (International Labour Organisation) in Geneva in May 1979. This meeting concentrated on all social and professional aspects of our profession concluding that controllers should be entitled special privileges (A.1.0). IFATCA was represented as an official observer.

2.3 Although this report is already 29 years old, it is of very interesting reading, and still of great importance to the ATC community as many recommendations are still as important now as they were then, not only focused on retirement and pension.

2.4 What is Retirement?

2.4.1 According to Wikipedia and for the aim of this paper:

“Retirement is the point where a person stops employment completely. A person may also semi-retire and keep a sort of retirement job, out of choice rather than necessity. This usually happens upon reaching a determined age, when physical conditions do not allow the person to work any more (through illness or accident), or by personal choice (usually in the presence of an adequate pension or personal savings). The retirement with a pension is considered a right of the worker in many societies, and hard ideological, social, cultural and political battles have been fought over whether this is right or not. In many western countries the right is mentioned in national constitutions.” (A. 1.1)

2.4.2 The Air Traffic Controller profession is, and will continue to be a unique profession, not only in the eyes of those directly involved, the general public, but also of the International Labour Organisation (ILO).

2.4.3 Existing IFATCA policy mentions that the retirement age should take into account the physiological demands and the occupational stress that the profession involves. Here information that is publicly available, not only on the Internet, but also in specialist libraries such as that at EUROCONTROL IANS in Luxembourg paints contrasting and sometimes controversial pictures not only for the controller, but also the wider aviation community. There seem to be two main positions that develop; those that agree that the ATCO (and other aviation professionals) is/are stressful/demanding and that require special consideration, and those that claim the opposite.

2.5 The positions for an earlier retirement / special consideration

2.5.1 The influence of ageing on ATCOs

2.5.1.1 “Human Factors in ATC” by Hopkin provides varied conclusions, but one pertinent age related factor is that long experience has the inherent potential to build habits that are entrenched, skills that are inflexible, the complacent belief that there are no new problems and over confidence that is indiscriminate to whether the ATCO is correct or not in making a particular decision. This publication goes on to state that the most experienced controllers are not necessarily the best when they are also the oldest. Experience is not necessarily an attribute when important new changes such as automation/computer assistance require the adaptation of ATCO working methods.

2.5.1.2 Ageing is generally associated with a progressive intolerance to fluctuations to natural circadian rhythms; deterioration in sleep restorative efficiency; decreasing of overall psychological fitness and capacity to cope with stress actuators (Åkerstedt, 1985a).

2.5.1.3 Åkerstedt also shows that age appears to correlate with “morningness” (the natural tendency to be a morning person). Most importantly Åkerstedt also underlines that ageing shows a greater susceptibility to the occurrence of rhythm disturbances, sleep disorders and psychic depression, which can in turn contribute to causing performance impairment (Åkerstedt & Torsvall, 1981)

2.5.1.4 As people get older they sleep less, but with increasing age there is less flexibility about when this sleep is taken. This means that shift work becomes more difficult with age, but these changes affect individuals in different ways.

2.5.2 The influence of stress on older ATCOs’ health

2.5.2.1 A recent study (October 2004) supported by the US National Institute of Mental Health and the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation suggests that the way ATCOs handle stress can affect whether they are at risk of developing high blood pressure later in life.

2.5.2.2 Robert M. Rose, M.D University of Texas Medical Branch stated that the study was the first to report that cardiovascular reactivity to work stress may be a long-term predictor of “incident hypertension”. He concluded that sustained high vigilance is required for successful air traffic control work. The report also summarised that it was not surprising, that in light of these considerations air traffic controllers have a high risk of hypertension especially as they get older.

2.5.2.3 The original 1974 study measured stress by recording blood pressure, heart rate and behavioural signs of anxiety every 20 minutes for five work days and compared these measures to the volume of air traffic under each controller’s command during those times.

2.5.2.4 The original 1974 study measured stress by recording blood pressure, heart rate and behavioural signs of anxiety every 20 minutes for five work days and compared these measures to the volume of air traffic under each controller’s command during those times.

2.5.2.5 We could therefore draw the conclusion that an increase in retirement age is directly linked with the possibility of developing a stress related medical condition.

2.5.3 The incidence of age related operational safety issues

2.5.3.1 The US Department of Transportation FAA completed in May 2004 a comprehensive analysis into the “Methodological Issues in the Study of Airplane Accident Rates by Pilot Age”. Although a study primarily focused towards our pilot colleague community, the nature of their work is similar to our own; responsible for aviation related safety, shift work (or time zone crossings) and dealing with constant change and increases in automation.

2.5.3.2 This document took into account previous studies (that had wildly conflicting results) and were considered alongside methodological issues such as (a) accident inclusion criteria; (b) pilot inclusion criteria; and (c) analytic strategy.

2.5.3.3 Overall, the comparisons and additional analysis indicated that these factors when added into the equation have a considerable impact on the study outcome. It was highlighted that there may be some risk associated with allowing pilots age 60 and older to operate complex, multi-engine aircraft with 10 seats or more in passenger operations. Therefore changes to the (now defunct) “Age 60 Rule” should be approached carefully.

2.5.3.4 The interactive role of the potentially negative impact of the ageing process and the safety enhancements that are assumed to accompany the gaining of additional operational experience have been assessed in a comprehensive overview of the subject by Guide and Gibson (1991). These authors cite the studies of Shriver (1953), who found that the physical abilities, motivation, skill enhancement, and piloting performance declined with age. Another scientist Gerathowohl (1978) found that both the psychological (cognitive) and physical capabilities of pilots deteriorated with age. This is equally true for the ATCO community.

2.5.4 The visible proof of a demanding profession

2.5.4.1 Concentrating less on the theoretical research and investigating the “Real Life” aspects of ATCO retirement the US, once again proves to be an example worth taking into account.

2.5.4.2 As is well publicised by our colleagues at NATCA, and reported in the press, the current and short term future ATCO shortage experienced in the USA is, in large, due to the amount of ATCOs eligible for retirement. The FAA expects that this trend will continue until around 2012.

2.5.4.3 A considerable amount of controllers are retiring before the US mandatory retirement age of 56. Of approximately 1,600 ATCO departures in 2007, more than half were retirements, and only a small percentage of those retirees were at mandatory retirement age. This evidently shows a direct correlation with the complex, high demanding nature of our profession and its effects on the ATCOs themselves. Not to mention the negative effects of an undesirable working atmosphere such as staff shortages, management/employee relationships and indecision regarding future prospects.

2.6 Against early retirement privileges/special consideration

2.6.1 The influence of experience on ATCOs’ professional abilities

2.6.1.1 Kay et al (1994) showed that pilots with more than 2,000 hours total time and at least 700 hours of recent flight time showed a significant reduction in accident rate with increasing age. These findings replicate and confirm the conclusions of Guide and Gibson (as mentioned previously) who found that recent experience gained by an air transport rated pilot, a major determinant in the aspect of flight safety.

2.6.1.2 Greater experience brings many changes for the ATCO. According to Hopkin in his book “Human Factors in ATC”, the controller becomes better at scheduling and prioritising tasks, and learns to cope with higher task demands. He/She avoids major blunders and major errors, adapts professional skills and knowledge to the particular characteristics of the managed airspace and learns to plan further in advance and to consider strategic as well as tactical implications. The ATCOs’ experience is helpful in the early diagnosis of problems, and learning to avoid non-optimum solutions even if their adverse effects are only trivial. The ATCO makes progressively subtler discriminations in the details and timing of chosen solutions, and provides a better service in achieving the basic objective of “Safe, Orderly and Expeditious” flow of traffic. Particular needs and objectives of various operators are better understood and he/she becomes more flexible in meeting them. With experience comes greater depth of knowledge and insight into one’s own tasks and those of the colleagues and supervisors with whom one must interact. Experience teaches which attitudes to use and when, professional norms and standards and the criteria applied by ATCOs to assess the professional competence of heir peers. The controller with more experience apparently gains in skill, self- confidence and satisfaction from a job well done.

2.6.1.3 It is of the PLC’s opinion this last statement could apply to any controller no matter what the age, as in the majority we all enjoy what we do and learn from our experiences.

2.6.2 The changing socio-economical and demographical environment

2.6.2.1 The “SHARE” (Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe) group based at the Mannheim Research Institute for the Economics of Ageing has conducted studies in the goal to compare data of health, socio-economic status and social and family networks of more than 30,000 individuals aged 50 and over in 11 countries which represent a balanced view of Europe in general (Sweden, Denmark; Austria, France, Germany, Switzerland, Belgium, The Netherlands, Spain, Italy and Greece. The group has also represented by using data from the Czech Republic, Poland and Israel).

2.6.2.2 They have found from their research that people who enjoy their work retire later in life. Health appears to be less important than is generally assumed. More important are the differences between national pension and social security systems. Contented employees stay longer as job satisfaction is important. Individual responsibility and professional recognition also predispose people to postpone their retirement for longer.

2.6.2.3 Where early retirement schemes are in place, people retire earlier, leaving positions unfilled and ultimately in our profession leading to restrictions in sector capacity due to staff shortages.

2.6.2.4 The general improvement in healthcare and diet has led to an increase in life expectancy not only, of course within the ATCO community, but also throughout the population. It is an obvious fact that more people taking advantage of pension schemes, means that the existing working population are obliged to pay, by working to an older age/or paying more into pension schemes, in order to finance the system and maintain social standards. The increase in life expectancy is not necessarily commensurate with an increase in mental health. This aspect may even deteriorate.

2.6.2.5 The global average life expectancy (for both sexes, at birth) is currently

67.2 years (65.0 years for males and 69.5 years for females) for 2005-2010 according to United Nations World Population Prospects 2006. This is a rise from 46 years (1950-1955), 65 years (2000-2005). The UN predicts that the average figure may reach 75 in 2045-2050, with the more developed countries reaching 82 years (Appendix 1.0 fig. 1.0)

2.6.2.6 Taking into account the reasons mentioned above, and faced with this shortage, it would be evident for an ANSP to consider taking advantage of the increasingly healthier, more mature workforce to reduce some of this deficit, by continuing to employ ATCOs after their normal retirement age.

2.7 Financial Considerations regarding Retirement

2.7.1 Systems providing financial security for the old are under increasing strain throughout the world reported the World Bank in 2002. The demographic change as described earlier in this paper is the main cause. For economists, policy makers and government officials are exploring ways to address issues such as ensuring financial security for the old and its’ payment, direct examples are highlighted below:

- In 1990, 9% of the worlds’ population were over 60; by 2030 the number will triple to 1.4 billion (mainly in Asia, and especially China).

- In Belgium it took 100 years for the share of population over 60 to double from 9 to 18%. In China the same transition will take only 34 years and in Venezuela 22 years.

- In 1989 Austria’s pension funds cost 15% of GDP and old age benefits absorbed 40% of public spending.

2.7.2 In almost all countries this means that government and public sector pensions could collapse their economies unless pension systems are reformed or taxes are increased. One method of reforming the pension system is to increase the retirement age.

2.7.3 The ILO has published a paper regarding the pension economic reforms in EU accession countries. They have concluded that this process has already started and these countries have made significant adjustments to such features of their public social insurance schemes as retirement age, benefit formulas, the treatment of special categories of workers, and the collection of pension formulas. A large majority of these countries have also increased the number of years work that are counted in computing pension, a change (they argue) that strengthens the relationship between benefits and lifetime earnings intended to encourage longer participation in the formal labour market.

2.7.4 There is no reason as to why this is not the case in other countries throughout the world. Klaus Schwab, Founder and Executive Chairman of the World Economic Forum in their “The Future of Pensions and Healthcare in a rapidly changing World” have stated that:

“The ageing of our societies is one of the most profound challenges that the world is facing today. New solutions are required to afford adequate and accessible retirement and healthcare services for the world’s ageing population in 2030 and beyond,”

2.7.5 Many countries also employ financial incentives to encourage people to work longer. In the United States and Germany, elderly workers receive wage or social security supplements. French and British workers receive pension bonuses for delayed retirement. Canada is even considering allowing workers to draw a partial pension before retiring.

2.7.6 Governments are trying to reduce dependence on state programs and encourage workers to save more by offering tax incentives for private pension schemes. In the United States, health savings accounts accumulate tax-free funds for medical costs in retirement.

2.7.7 Finally, on a personal level, the rising cost of living during retirement is a serious concern to many adults. We should also be considering the impact of a longer retirement as:

- Your assets will need to provide income for that many more years. A retirement “nest egg” of US$500,000, invested to earn a 7% annual return, will provide $47,000 per year income over a 20-year retirement before being depleted. But when spread over a 30-year retirement, you can only draw $40,000 per year in order to make it last 30 years. (35 years – $38,600)

- Inflation. Even at a low inflation rate, costs multiply dramatically over several decades. If your lifestyle costs $30,000 per year today, after 35 years at an inflation rate of 3% annually it would cost nearly $85,000. If inflation averaged 4%, the cost in 35 years would be over $118,000.

2.8 Current Retirement Trends Around the World

2.8.1 Information regarding the current trends in ATCO retirement age is almost impossible to research. It would require further study, one that time does not permit for this WP.

2.8.2 The Portuguese MA has recently accepted a raise in their retirement age in return for increased benefits. The UK MAs’ major ANSP has reformed the pension schemes for new ATCOs joining the company by reducing the benefits available at retirement age in an attempt to cut pension-funding costs. The Swiss regulator after pressure from its ANSP has changed the requirement for Supervisors to hold an Air Traffic Control licence. The Supervisors now hold “Safety Related Task” licences possibly in a bid to increase retirement age and to open the position up to those without ATCO experience. In Canada retired ATCOs have been rehired to meet demand working on individual contracts.

2.8.3 It is possible, however, to study trends in retirement age and pension reform in general.

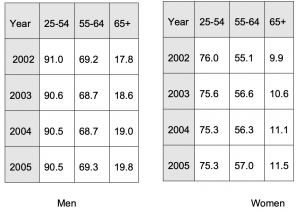

2.8.4 In a document presented to US Congress, it was shown that in the last decade that “Labour Force Participation Rates”, or those still in employment after the age of 55, is starting to increase, after a reduction during the 1980s and 90s. This is especially prevalent in the over 65 group and in women thanks to a greater proportion of women in the workforce. (Appendix 1.2 fig. 1.2)

2.8.5 Ann Mettler, an executive director of the Lisbon Council, a Brussels-based think tank was asked if increasing the age of retirement a viable solution to the decline of the European workforce?

“It is certainly one of the solutions, and should occur anyway considering the incredible increase in life expectancy. Consider this: in 1970, the average woman in OECD countries drew a pension for 14 years. By 2004 that figure had increased to 23 years. Consider also that in 2050, there will be one person over the age of 65 for every two people of working age compared to five people of working age in 2000. As these figures demonstrate, inaction is not an option.”

2.9 Retirement Age Adaptation as a Solution to ATCO Staff Shortages

2.9.1 IFATCA has estimated the global lack of controllers to be about 3,000 (Press Release 20th March 2008, WP No.166 “Staff Shortage in ATC” 47th Annual Conference Arusha, Tanzania).

2.9.2 Many ANSPs face chronic staff shortages. This has in some instances led to the closure of airspace at various times of the day, as for example the case in Australia. An ANSP may feel that to increase retirement age would address the situation. It should be noted that before an ANSP considers this solution it would have already used the “overtime” option, leading to a more fatigued and older workforce less likely to be able to cope with a constantly increasing traffic load.

2.9.3 The decision to increase retirement age would frustrate those controllers most affected (those close to the previous retirement age), and may block potential promotion opportunities for younger ones.

2.9.4 The UK Government in its official response to the implementation of the common European ATCO licence debate regarding whether a mandatory retirement age should be implemented stated:

“During the negotiations on this Directive, some States have argued strongly that there should be set minimum ages for controllers. We have consistently pushed our view that flexibility is required and that it should be up to the service provider to decide what age its’ controllers should be able to start and finish employment providing that the appropriate medical and competency requirements are met.”

2.9.5 The PLC is of the opinion that ANSPs alone should not have the overall power to change ATCO retirement ages.

2.10 Preparation for Retirement

2.10.1 There exists a potential issue that current IFATCA policy does not address. This relates to the preparation of ATCOs with respect to a forthcoming retirement.

2.10.2 As with other professions, ATC assigns its most senior and responsible positions to its older and more experienced ATCOs. These ATCOs then retire from a highly responsible position. This may be a just acknowledgement of their abilities, may also be counterproductive as preparation for an “afterlife” becomes even more important. A more appropriate preparation may be to diminish responsibilities and shift work during his/her “final” years. Due to the phenomenon of shift work, ATC has the problem that many controllers share their leisure activities with their work colleagues as they are often off at the same “unusual” times of the day. This aids camaraderie at work, but may mean that at retirement the many social and leisure activities, as well as the standard work relationships may end.

2.10.3 Provision for early retirement in individual cases for clinical reasons or factors such as burnout must always be made. Retirement plans must be based on realistic expectations, particularly those regarding further employment either related, or unrelated to ATC. While every problem cannot be foreseen, many could be avoided through practical counselling about the real prospects available in the “afterlife”. This is particularly important if the ATCO has certain flexibility over the timing of the retirement. Ideally the plans for retirement should have been well planned in advance, so that the last few years of work can act as a “winding down” process.

2.10.4 A retirement preparation course may include the following topics:

- Attitude Toward Retirement

- Financial Security

- Leisure Interests

- Dependents

- Perception of Age

- Health Perception

- Current/Future Life Satisfaction

- Adaptability

- Familial and Marital Issues

- Replacement of Work Function

Conclusions

3.1 The research has identified strong points that indicate that an Air Traffic Controller should be entitled to special privileges regarding retirement age. At the same time IFATCA should not dismiss the opportunity to address the issues of the near future for example increases in automation.

3.2 Considering the facts discussed on the previous pages, there seems to be no reason to alter the general meaning and format of the existing policy. The existing policy recognises the fact that the Air Traffic Control profession is of a particularly stressful nature. Provision is also made to the use of a superannuation pension scheme after retirement and considers the opportunity to take early retirement. It also addresses those controllers who should wish to continue working after the normal retirement age.

3.3 Existing policy does not take into account the global demographic shift. The fact that the average age of our population is increasing, as is life expectancy has been recognised by other aviation related professions, and by governmental bodies. The increase in life expectancy is not necessarily commensurate with an increase in mental health. This aspect may even deteriorate.

3.4 Current trends in Retirement and Pensions around the globe show a similar pattern where retirement will be taken later, and requiring funding changes to pension schemes in order to address the demographic shift.

3.5 Systems providing financial security for the old are under increasing strain throughout the world. On a personal level, constant increases in the cost of living, refusal of employers to increase wages due to economic pressures and changes to pension plans, should create a real worry to all controllers throughout the world with respect to retirement.

3.6 As our profession will evolve in the mid to long term future to one of a more automated, air traffic managerial position our ability to manage this traffic may well allow us to work until an older age. The continuous flow of air traffic 24 hours a day, will however, continue to imply that air traffic controllers are required to work around the clock imposing the stress associated with shift work.

3.7 ANSPs wishing to address a chronic shortage of qualified Air Traffic Controllers should not consider increasing the national retirement age for ATCOs. This apparent “solution” is in effect detrimental to the overall ATC system as it does not address the root of the problem which is a consistent lack of suitably qualified staff that is available to cope with a constant increase in traffic demand. The PLC is of the opinion that ANSPs alone should not have the overall power to change ATCO retirement ages.

3.8 The actual process of retirement can be an emotional turmoil for a particular individual. An air traffic controller may lose not only his or her profession, but also may lose the ability to network socially.

3.9 A formal process should be made available in order to facilitate preparation for retirement.

3.10 Existing IFATCA policy should be reviewed to question the demographic “shift” of population.

Recommendations

4.1 New policy to be added: page 4 1 5 1:

5.1.5 ANSPs must not increase retirement ages in an attempt to address ATCO staff shortage issues.

5.4 Preparation for retirement

A course in order to prepare ATCOs should be made available by their employer in order to facilitate the transition between an active controlling career, and becoming a retired professional.

References

- World Bank Report on “Averting the Old Age Crisis”.

- Wikipedia.

- Recent Trends in Pension Reform and Implementation in the EU Accession Countries ILO.

- CRS Report for Congress (US) Older Workers: Employment and Retirement Trends.

- United Nations 2007 Report on Life Expectancy Data.

- Allianz Knowledge.

- Åkerstedt & Torsvall, 1981 + 1985 Various Works.

- “Human Factors in ATC” by Hopkin.

- US National Institute of Mental Health and the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation.

- The US Department of Transportation FAA “Methodological Issues in the Study of Airplane Accident Rates by Pilot Age” 2004.

- Lay et al. 1994.

- “SHARE” (Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe).

- World Economic Forum “The Future of Pensions in a Rapidly Ageing World”.

- ILO Meeting of Experts on Problems Concerning Air Traffic Controllers 8-16th May 1979.

Appendix 1

A1.1 – Figure 1.1 – IFATCA MA data when compared with 2007 United Nations Life Expectancy Data*

| Rank* | Country | Life Expectancy at Birth | National Retirement Age | ATCO Retirement Age | |||

| Overall | Male | Female | Male | Female | |||

| World | 67.2 | 65.0 | 69.5 | ||||

| 1 | Japan | 82.6 | 79.0 | 86.1 | 60 | 60 | 60 |

| 2 | Hong Kong | 82.2 | 79.4 | 85.1 | 60 | ||

| 3 | Iceland | 81.8 | 80.2 | 83.3 | 70 | 70 | 63 |

| 4 | Switzerland | 81.7 | 79.0 | 84.2 | 65 | 64 | 55 |

| 5 | Australia | 81.2 | 78.9 | 83.6 | 65 | 65 | 50 |

| 6 | Spain | 80.9 | 77.7 | 84.2 | 65 | 65 | 52 |

| 7 | Sweden | 80.9 | 78.7 | 83.0 | 65 | 65 | 60 |

| 8 | Israel | 80.7 | 78.5 | 82.8 | 65 | 62 | 65 |

| 9 | France | 80.7 | 77.1 | 84.1 | 65 | 65 | 55 |

| 10 | Canada | 80.7 | 78.3 | 82.9 | 50 | ||

| 11 | Italy | 80.5 | 77.5 | 83.5 | 60 | ||

| 12 | Norway | 80.2 | 77.8 | 82.5 | 67 | 67 | 65 |

| 13 | Singapore | 80.0 | 78.0 | 81.9 | 55 | ||

| 14 | Austria | 79.8 | 76.9 | 82.6 | 65 | 60 | 60 |

| 15 | Netherlands | 79.8 | 77.5 | 81.9 | 58 | 58 | 55 |

| 16 | Greece | 79.5 | 77.1 | 81.9 | 65 | 65 | 65 |

| 17 | Belgium | 79.4 | 76.5 | 82.3 | 65 | 60 | 55 |

| 18 | Malta | 79.4 | 77.3 | 81.3 | 61 | 61 | 61 |

| 19 | United Kingdom | 79.4 | 77.2 | 81.6 | 65 | 65 | 60 |

| 20 | Germany | 79.4 | 76.5 | 82.1 | 65 | 63 | 55 |

| 21 | Finland | 79.3 | 76.1 | 82.4 | 65 | 65 | 65 |

| 22 | Cyprus | 79.0 | 76.5 | 81.6 | 60 | ||

| 23 | Ireland | 78.9 | 76.5 | 81.3 | 65 | 65 | 65 |

| 24 | Luxembourg | 78.7 | 75.7 | 81.6 | 57 | ||

| 25 | Chile | 78.6 | 75.5 | 81.5 | 65 | 60 | 65 |

| 26 | Denmark | 78.3 | 76.0 | 80.6 | 65 | 65 | 55 |

| 27 | Slovenia | 77.9 | 74.1 | 81.5 | 55 | ||

| 28 | Barbados | 77.3 | 74.4 | 79.8 | 60 | ||

| 29 | Czech Republic | 76.5 | 73.4 | 79.5 | 62 | 62 | 62 |

| 30 | Albania | 76.4 | 73.4 | 79.7 | 65 | 60 | 65 |

| 31 | Uruguay | 76.4 | 72.8 | 79.9 | 70 | 65 | 70 |

| 32 | Mexico | 76.2 | 73.7 | 78.6 | 60 | ||

| 33 | Croatia | 75.7 | 72.3 | 79.2 | 65 | 60 | 55 |

| 34 | Poland | 75.6 | 71.3 | 79.8 | 65 | 60 | 60 |

| 35 | Panama | 75.5 | 73.0 | 78.2 | 62 | 62 | |

| 36 | Argentina | 75.3 | 71.6 | 79.1 | 65 | ||

| 37 | Bosnia & Herzegovina | 74.9 | 72.2 | 77.4 | 65 | 60 | 65 |

| 38 | Slovakia | 74.7 | 70.7 | 78.5 | 60 | ||

| 39 | Malaysia | 74.2 | 72.0 | 76.7 | 55 | ||

| 40 | Aruba | 74.2 | 71.3 | 77.1 | 55 | 55 | 55 |

| 41 | Serbia | 74.0 | 71.7 | 76.3 | 65 | 58 | 65 |

| 42 | St. Lucia | 73.7 | 71.8 | 75.6 | 65 | 65 | 65 |

| 43 | Bahamas | 73.5 | 70.6 | 76.3 | 60 | ||

| 44 | Bulgaria | 73.0 | 69.5 | 76.7 | 65 | 63 | 57 |

| 45 | Lithuania | 73.0 | 67.5 | 78.3 | 62 | ||

| 46 | Latvia | 72.7 | 67.3 | 77.7 | 65 | 62 | 50 |

| 47 | Jamaica | 72.6 | 70.0 | 75.2 | 60 | ||

| 48 | Sri Lanka | 72.4 | 68.8 | 76.2 | 55 | ||

| 49 | Brazil | 72.4 | 68.8 | 76.1 | 65 | 60 | 65 |

| 50 | Algeria | 72.3 | 70.9 | 73.7 | 60 | 55 | 60 |

| 51 | Dominican Republic | 72.2 | 69.3 | 75.5 | 60 | 60 | 60 |

| 52 | El Salvador | 71.9 | 68.8 | 74.9 | 65 | 65 | 65 |

| 53 | Turkey | 71.8 | 69.4 | 74.3 | 60 | 55 | 60 |

| 54 | Peru | 71.4 | 68.9 | 74.0 | 65 | 65 | 65 |

| 55 | Estonia | 71.4 | 65.9 | 76.8 | 63 | 63 | 55 |

| 56 | Georgia | 71.0 | 67.1 | 74.8 | 65 | 60 | 65 |

| 57 | Iran | 71.0 | 69.4 | 72.6 | 60 | ||

| 58 | Suriname | 70.2 | 67.0 | 73.6 | 55 | ||

| 59 | Trinidad & Tobago | 69.8 | 67.8 | 71.8 | 60 | ||

| 60 | Belarus | 69.0 | 63.1 | 75.2 | 50 | ||

| 61 | Moldova | 68.9 | 65.1 | 72.5 | 62 | ||

| 62 | Fiji | 68.8 | 66.6 | 71.1 | 65 | 65 | 65 |

| 63 | Ukraine | 67.9 | 62.1 | 73.8 | 60 | 55 | 50 |

| 64 | Guyana | 66.8 | 64.2 | 69.9 | 55 | ||

| 65 | Bolivia | 65.6 | 63.4 | 67.7 | 65 | ||

| 66 | Russia | 65.5 | 59.0 | 72.6 | 60 | 55 | 50 |

| 67 | Nepal | 63.8 | 63.2 | 64.2 | 58 | ||

| 68 | Yemen | 62.7 | 61.1 | 64.3 | 60 | ||

| 69 | Ghana | 60.0 | 59.6 | 60.5 | 60 | ||

| 70 | Madagascar | 59.4 | 57.7 | 61.3 | 55 | 55 | 55 |

| 71 | Togo | 58.6 | 56.7 | 60.1 | 55 | ||

| 72 | Papua New Guinea | 57.2 | 54.6 | 60.4 | 55 | ||

| 73 | Niger | 56.9 | 57.8 | 56.0 | 55 | ||

| 74 | Gabon | 56.7 | 56.4 | 57.1 | 55 | ||

| 75 | Benin | 56.7 | 55.6 | 57.8 | 55 | ||

| 76 | Congo Brazzaville | 55.3 | 54.0 | 56.6 | 55 | ||

| 77 | Mali | 54.5 | 52.1 | 56.6 | 55 | ||

| 78 | Kenya | 54.1 | 53.0 | 55.2 | 55 | ||

| 79 | Ethiopia | 52.9 | 51.7 | 54.3 | 55 | ||

| 80 | Namibia | 53.9 | 52.5 | 53.1 | 65 | ||

| 81 | Uganda | 51.5 | 50.8 | 52.2 | 55 | ||

| 82 | Botswana | 50.7 | 50.5 | 50.7 | 45 | ||

| 83 | South Africa | 49.3 | 48.8 | 49.7 | 65 | 65 | 60 |

| 84 | Nigeria | 46.9 | 46.4 | 47.3 | 60 | ||

| 85 | Rwanda | 46.2 | 44.6 | 47.8 | 55 | ||

| 86 | Angola | 42.7 | 41.2 | 44.3 | 65 | ||

| 87 | Swaziland | 39.6 | 39.8 | 39.4 | 60 | ||

*If your MA is not featured, it is because you have not completed the IHB, or provided complete information.

A.1.2 – Figure 1.2 – Labour Force Participation Rates (% of Americans in employment in different age groups)

A.1.3 – ILO Report Conclusions

63. Several Government and Worker experts referred to early retirement pensions for air traffic controllers existing in various countries. For example, in one country this age was fixed at 55, whereas in some other countries their retirement age was set at 50. It was pointed out, however, that the great majority of ATCOs were disqualified from their work long before reaching the regular compulsory retirement age of other employees. In one country, ATCOs were entitled to retire with a full pension after 20 years of service, regardless of age. The Worker experts felt that this example might usefully be followed in all countries.

64. The Worker experts stressed that the age of retirement must be lower for ATCOs than for other groups of workers, in view of the unique nature of their work and in the interests of safety. The medical studies undertaken so far and experience had shown that ATCOs’ efficiency, and in particular their powers of concentration, tended to diminish after a certain age and this created risks for aviation safety. There should be available to ATCOs optional early retirement but there should be an age beyond which they should not continue to be employed. Since density of air traffic and conditions of work varied from country to country, the exact early age of retirement might be determined by negotiation at the national level in each case.

65. As regards the level of pensions the Worker experts pointed out that retirement at an early age penalised ATCOs because not only did they accumulate fewer years of service than other workers but they also had to retire at an age when other workers at that age were at their period of highest remuneration. They therefore urged that measures be taken to compensate ATCOs for the disadvantages of early retirement at an early age, such as a supplementary pension. In one country, such a supplementary benefit was paid between the ages of 55 (the retirement age of ATCOs) and 65, after which retired ATCOs were paid the same pensions as other people. The pensionable remuneration should be based on total remuneration (basic pay plus allowances).

66. There was general agreement that there should be a compulsory age of retirement for ATCOs, probably earlier than that applicable to other workers, which should be determined by negotiation at the national level, and that such earlier retirement should not adversely affect the level of pension benefits of ATCOs.

A.1.4 – The idea of “Retirement”

In most countries, the idea of a fixed retirement age is of recent origin, having been introduced during the 19th and 20th centuries. Before then, the absence of pension arrangements meant that nearly all workers continued their activity until death, or relied on the support of their family. Retirement age varies from country to country and is generally situated between 60 and 70. Occasionally certain jobs, often the most dangerous or fatiguing ones in particular, have an earlier retirement age.

In some cases ATCOs retire at the same age as other “public” employees. In others they retire after a fixed number of years as a controller, so that retirement age depends on age at entry to the profession. Some states have inflexible policies on retirement age; others are more so, subject to retained proficiency and medical competence. Sometimes minimum and maximum retirement ages are stipulated. Where “early” retirement has been negotiated for local ATCOs by bodies such as local unions and professional associations through IFATCA on their behalf, this can seem beneficial to those early in their career, but much less so as they approach their retirement.

Older ATCOs may find it more difficult to adapt successfully to new equipment or procedures and find the job more tiring. However, after evaluating the various evidence available, there is insufficient evidence in terms of performance or safety alone to justify stringent fixed policies of retirement age, as individuals differ so much in their abilities, medical fitness and requirements as they age. Administratively speaking, it may be much easier for ANSPs to plan their workforce however, applying a definite retirement age. In this case the age should reflect the “unique nature” (to return to the initial ILO observation) of the Air Traffic Controller profession by being significantly earlier than the official retirement age.