DISCLAIMER

The draft recommendations contained herein were preliminary drafts submitted for discussion purposes only and do not constitute final determinations. They have been subject to modification, substitution, or rejection and may not reflect the adopted positions of IFATCA. For the most current version of all official policies, including the identification of any documents that have been superseded or amended, please refer to the IFATCA Technical and Professional Manual (TPM).

57TH ANNUAL CONFERENCE, Accra, Ghana, 19-23 March 2018WP No. 156Competence AssessmentPresented by PLC |

Summary

The competence of ATCOs should be assessed regularly. Most ANSP’s have a process in place for competence assessment, being observed while working on the job or through a practical test on the simulator. Recent developments are the implementation of competency-based assessment and pursuing a weighted average of multiple observations, instead of a snapshot. Both ICAO and Eurocontrol have guidelines on the subject.

A recent survey of PLC revealed interesting data on how competence assessment is conducted around the world and what differences exist between countries. While most ANSP’s are satisfied about the process in general, there is always room for improvement. In the African region, the idea is still in its infancy.

IFATCA has addressed competence assessment for 30 years; this paper aims to refresh existing policy and bring terms and requirements in line with ICAO.

Introduction

1.1 Competence assessment of air traffic controllers (also known as proficiency checking) was a subject of discussion in Professional and Legal Committee (PLC) meetings in 2017. It was put on this year’s work programme, to check the existing IFATCA policy and address the presentday issues of data protection and privacy.

1.2 This paper gives an overview of the evolvement of competence assessment in air traffic control, reviews existing IFATCA policy and links the subjects ‘performance assessment’ and ‘use of recorded data’ to ensure a safe working environment where every ATCO is fairly appraised.

Discussion

2.1 Performance assessment in organisations

2.1.1 For decades, individuals have been involved in the assessment of work performance of others. In the 1950s companies used personality-based systems to measure performance, quickly followed by more fair performance appraisals that were actually measuring if objectives and goals were met.

2.1.2 During the 1970s, companies were so obsessed with measuring the performance of their employees that assessments were only about ‘finding flaws’. In air traffic control, this resulted in performance appraisal being an important tool in the error reporting system for ANSP’s. For instance, the FAA used check forms for human error to identify the causes of incidents. Controller proficiency and incident involvement were lumped together in a system that was far from the Just Culture we now aim for.

2.1.3 In the next 20 years a more holistic approach was developed where self-awareness, communication, teamwork and the ability to handle emotions became more important. Recently, performance management evolved into systems that seek multiple feedback sources – known as “360 degree” or “multi-source” feedback.

2.2 An integrated and ongoing process

2.2.1 The integrated concept of competence as a holistic set of knowledge, skills and attitudes was developed in the 1990s. Historically too much emphasis had been placed on determining whether trainees could pass exams and insufficient emphasis on whether they could perform in the role expected. A good assessment system does not assess each attribute separately with a checklist, but is integrated and goes well beyond solely task skills.

2.2.2 Competence assessment should never be a snapshot, but a continuous process. A typical example of such a process is shown in the figure below.

Figure 1: Competence assessment as an ongoing process, 2017 Cognology – Melbourne, Australia

2.2.3 The view on competence assessment as an integrated and ongoing process shaped the thinking about performance appraisal in aviation, and can be derived from the guidelines on competence assessment from ICAO (DOC 10056) and Eurocontrol. The regulations and guidance will be explained in paragraph 2.4.

2.3 Competency frameworks

2.3.1 In the 1990’s, the competency based view became popular in organisations. Competencebased assessment is a specific type of performance assessment, where organisations develop a set of competencies; desirable knowledge, skills and attitudes that form standards of performance. Competence-based assessment is especially suitable for jobs that are highly task-oriented. In the years that followed, many organisations developed competency models to help with performance management and career development.

2.3.2 In air traffic control, competencies are no longer indispensable. Like in other industries, competency frameworks were developed for selection and training purposes. In 2006, a training expert and two ATCOs of Air Traffic Control, The Netherlands (LVNL) published an article in the International Journal of Aviation Psychology, in which they showed “how competence-based assessment design may lead to more effective learning processes and better pass-fail decisions in ATC simulator and OJT”. (Oprins, Burggraaf & Van Weerdenburg, 2006, page 31)

2.3.3 It did not take long for ANSP’s to realise that the same models could also be used to assess the performance of ATCOs after their ab-initio training. In many countries competency based assessment on-the-job is used as the primary way of proficiency checking for air traffic controllers, complemented by theory exams and sometimes a simulator assessment.

2.4 Competence assessment for ATCOs: development and legal framework

Legal framework

2.4.1 ICAO Annex 1, the regulative framework for personnel licensing, describes mostly how ATCOs shall be trained to initially receive their license. On renewing the license, the manual does not have many prescriptions. The only standards are related to a number of hours or months (ICAO Annex 1, (4.5.2.2.1 b) 1) and 2)). ICAO aims to address this issue in Amendment 6, from the year 2020.

2.4.2 On the European level, there are extensive regulations on ATCO’s licencing and certification. EU Commission Regulation 805/2011 states:

“The competence of each air traffic controller shall be appropriately assessed at least every three years.”

EU Commission Regulation 2015/340 extensively prescribes the requirements for licensing and certification. For example:

| AMC1 ATCO.B.020(e) Unit endorsements VALIDITY OF THE UNIT ENDORSEMENT

When establishing the validity of a unit endorsement, unit standards of performance and seasonal variations should be taken into account. Appropriate means should be in place to monitor the competence of the air Traffic controllers. The means should be proportionate to the validity time. If the proposed validity time of the unit endorsement exceeds 12 months additional means should be in place to monitor and ensure the continuous competence of the air traffic controllers. If the ATC unit is proposing to increase the validity time of the unit endorsement a safety assessment should be conducted. The safety assessment may cover several units. AMC1 ATCO.B.020(g)(3) Unit endorsements PRACTICAL SKILLS ASSESSMENT FOR REVALIDATION OF THE UNIT ENDORSEMENT (a) If the assessment of practical skills is taking the form of a dedicated assessment consisting of a single assessment or a series of assessments, the last assessment declaring the license holder competent should take place within the 3-month period immediately preceding the unit endorsement expiry date. (b) If the assessment of practical skills is taking the form of a continuous assessment by which the air traffic controller’s competence is assessed along a defined period of time, the formal conclusion on declaring the license holder competent should take place within the 3-month period immediately preceding the unit endorsement expiry date. |

Guidelines and manuals: Eurocontrol and ICAO

2.4.3 In 2016, ICAO released DOC 10056: Manual on Air Traffic Controller Competency-based Training and Assessment. The manual is based on the knowledge, skill and experience requirements detailed in Annex 1 – Personnel Licensing and the ATC competency framework described in the Procedures for Air Navigations Services – Training (PANS-TRG, Doc 9868). Among the contributors to this document were Airways New Zealand, Eurocontrol, United States’ FAA, Nav Canada and IFATCA.

2.4.4 DOC 10056 emphasizes the importance of competency-based training and assessment. Competence assessment is only effective when:

a) Clear performance criteria are used;

b) An integrated performance is observed;

c) Multiple observations are taken;

d) Assessments are valid;

e) Assessments are reliable.

2.4.5 One of the requirements of competency-based training and assessment is that multiple observations are conducted.

| 2.7.1.3 Multiple observations are undertakenTo determine whether or not a trainee has achieved the interim and/or final competency standard, multiple observations must be carried out.

3.2 Practical instructing and assessing One of the requirements of competency-based training and assessment is that multiple observations are conducted throughout a course or training session. |

On the tasks and responsibilities of an assessor, DOC 10056 advises:

| 3.5 Assessors In a competency-based environment, the assessor:

a) gathers evidence of competent performance through practical observations (and any associated interviews), and b) analyses all the evidence to determine if the trainee’s performance demonstrates that he/she has acquired or maintained the competencies detailed in the adapted competency model. The assessor of the practical performance of a trainee should: a) Be able to assess an integrated performance and, at the same time, evaluate the performance of separate competencies; b) Conduct assessment(s) by gathering evidence of competent performance Assessors obtain and assess evidence to determine if a trainee is competent. To do this effectively the assessor should be capable of sound judgement, possess analytical skills and be able to distinguish crucial or essential issues from less important ones; c) Use the tools provided in the assessment plan d) Debrief the trainees in a manner that will aid their progress. |

2.4.6 In 2004 the European Organisation for the Safety of Air Navigation developed the document ‘Guidelines for Competence Assessment’ (latest version 2.0 was released in 2005). They introduce the term competence assessment scheme to describe “the process by which an ANSP assures the Designated Authority that all personnel involved in safety related tasks are competent” (Eurocontrol – 2005, page 9). The assessment process should always be supplemented by other references and supporting evidence, such as training records, theoretical checks, discussions and interviews.

| 5. METHODS OF COMPETENCE ASSESSMENT Competence may be assessed by a system of:

a) Continuous assessment; or b) Dedicated practical check; or c) Combination of (a) and (b) above; and d) Oral Examination and/or a written or Computer-Based Training (CBT) test of the controller’s knowledge of Unit and national ATC procedures. |

2.4.7 The ‘Guidelines for Competence Assessment’ differentiates between assessment where assessors observe their colleagues while performing their normal ATCO duty, and dedicated assessment, where the assessor sits with the controller for the sole purpose of observing. In the latter, the assessor is not involved in any other tasks.

2.4.8 Both ICAO and Eurocontrol guidelines emphasize the importance of multiple observations (continuous assessment) to assess competence the most natural way. Instead of using a ‘snapshot’ where one can prepare for and show desired behaviour, ATCOs should be assessed regularly on the position during the year. This gives a more weighted average of performance, while also taking away the stress of a ‘checkout test’.

2.5 Assessing each other

2.5.1 The scarcity in ATM personnel and the extreme specialisation of the tasks make it often impossible to use dedicated assessors that stand apart from the group of operational controllers. That is why in most cases a group of selected ATCOs assess the proficiency of their colleagues – and each other. A benefit of this system is that assessors are active controllers in the same unit as their subjects, making sure they are current, familiar with the way of working and used to the traffic movements. A downside is that assessors and controllers work in the same team and may know each other well, leaving potential for biases.

2.5.2 It is obvious that the group of assessors should be selected and trained through a dedicated process that addresses this delicate subject in terms of ethics. Simply appointing experienced supervisors or OJTI’s and making them assessor will most like not get sufficient support from the work floor. Assessors should come together regularly to reflect on their performance and receive training.

2.5.3 Conflicts between controllers, both in and outside the workplace, can affect objectivity of assessments. ATCOs should be able to refuse certain assessors in case of personal conflict.

2.6 Competence assessment around the world: examples and issues

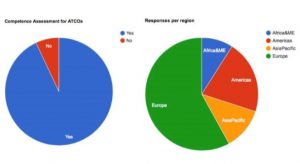

2.6.1 Last year, IFATCA PLC asked member associations to fill out a digital questionnaire on competence assessment. The goal of this survey was to check how competence assessment is performed around the world and to inquire if there are concerns about the way things work. The survey was sent out by e-mail and also highlighted at IFATCA Regional Meetings. 43 member associations replied, providing a great amount of insights in the matter. Most replies came from Europe and North and Central America, but also many other countries filled out the questionnaire. Competence assessment exists in 93% of the member states that replied. In Uruguay, Kenya and Gambia there is no active competence assessment for ATCOs.

2.6.2 Although not all countries from the African continent replied, an enquiry at the IFATCA AFM regional meeting revealed that many members in the AFM region do not have competence assessment in place, apart from Zambia and Togo.

Competence assessment in practice

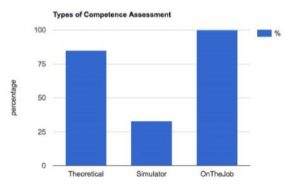

2.6.2 In most countries, competence assessment entails a combination of one or more practical onthe-job checks (all of the respondents) and a theoretical test (85% of the respondents). One third of the respondents indicated that their competence is also checked in simulator exercises. This can be a high-intensity exercise that is complementary to regular on-the-job assessment, or recurrent training that needs to be passed. In Europe, many ANSP’s are implementing assessed recurrent training because of new EASA requirements.

2.6.3 There are differences between countries in how competency assessment works in practice. In most cases, there is an on-the-job proficiency check that has to be passed. An assessor sits next to an ATCO working live traffic, for about one to two hours per single rating. The regularity of these checks varies from four times a year to once every three years among ANSPs around the world, but once a year is most common. This is often combined with a yearly theoretical test with questions about rules, procedures and general ATCO knowledge such as air law and meteorology. If the result of the competence assessment is not satisfactory, an ATCO will typically be given a training programme in a simulator environment to overcome deficiencies. Thereafter they will work a number of shifts under supervision of an OJTI to oversee their performance.

2.6.4 Theoretical tests vary from a yearly multiple-choice test, with a common pass rate between 70% and 80%, to oral testing (questions during or after the practical assessment). Nowadays it is also common to check small parts of the theory more regularly, i.e. random exam questions during the self-briefing when starting a shift.

Assessors

2.6.5 Who is appointed to assess the performance of an ATCO differs per country? Generally, all assessors are experienced ATCOs, who have an OJTI endorsement. In some countries, only unit or sector supervisors assess the work of their controllers. Most ANSPs, however, have a separate assessor role in place next to the role of instructor. There may be a financial incentive for ATCOs that choose to be an assessor. There are countries in which management has no say in the selection of assessors; for instance, in Iceland they are chosen by the ATCOs themselves.

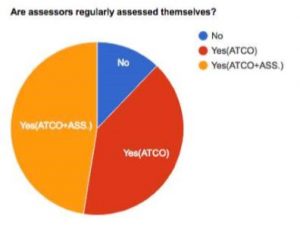

2.6.6 The survey revealed that there are countries in which assessors, once elected, are relieved from any checks on their own competence. A distressing percentage of 13% of respondents indicated this. In most countries assessors are also assessed themselves while working on the job, and in about 50% of the cases they are also reviewed on how they perform their assessor duties. This can be in a live environment, but also by group meetings where training experts provide training and feedback on their reports and proceedings.

Continuous Assessment

2.6.7 Competence assessment is often a snapshot, not a weighted average of many observations. Typically, the practical ‘check-up’ is performed once a year and has to be passed. However, the survey indicates that only three out of 43 respondents use continuous assessment instead of pass/fail (Belgium, Hungary and The Netherlands).

2.6.8 For instance, in The Netherlands, a few OJTI’s are trained as assessors. They will randomly assess their colleagues during their work, when there is a reasonable amount of traffic. This can be done when working alongside (e.g. as planning controller) or when sitting behind the ATCO (dedicated assessment). Usually there will be around 10 of those assessment moments a year. They are not pass/fail: only when multiple observations indicate that the ATCO is not performing according to standards, the group of assessors will come together and a training plan is designed. ATCOs are always personally informed about points of improvement, but not when the result of the observation was satisfactory. Assessors come together once or twice a year to receive training and feedback on the way they observe and write reports.

Issues with competence assessment

2.6.8 In general, the survey shows that ATCOs have no major concerns about the way competence assessment is performed in their organisation. Nobody likes exams and checks, but many respondents say they believe the system works quite well.

2.6.9 There are many remarks about the validity and subjectivity of competence assessment. In most ANSPs annual checks are a snapshot and subjective depending on the traffic conditions on the evaluation day. An assessment done when there is very low traffic, does not determine the ATCO’s proficiency in complex and busy situations. Furthermore, during a pre-planned check, a controller is prepared and able to exactly follow procedures ‘by the book’, while this might not be the case when evaluation is taking place without notice.

2.6.10 Common issues also involve frequency of assessments and quality of the assessors. Some respondents complain that, due to staff shortages, their practical assessments do not take place as frequently as the procedures prescribe. Furthermore, the way assessors are selected and trained and trained is often a point of criticism.

2.6.11 There are indications from MAs that their employer is intending to link results of competency assessment to the amount of salary a controller receives. This is a very distressing development. Competency and performance of ATCOs shall never be linked to remuneration.

2.7 IFATCA on competence assessment

2.7.1 IFATCA first officially addressed the proficiency checking of air traffic controllers more than 37 years ago, with a progressive paper for that time (WP 39 – Toronto 1980). Because of the sensitive subject the conclusions were presented as guidance material. A year later, the most important recommendations were accepted as IFATCA policy (Cairo 1981). Criteria for the selection of assessors (then called ‘check-controllers’) were added in 2002, including policy on training and periodical assessment of these assessors (WP 161 – Cancun 2002).

2.7.2 In 2007 PLC performed an extensive review of the IFATCA Policy on Training (WP 164 – Istanbul 2007). The policy on proficiency checking was found to be still valid.

2.7.3 The current IFATCA Policy on competence assessment is listed below.

| TRNG 10.4.4 PROFICIENCY CHECKING IFATCA policy is:

The results of proficiency checks should be treated confidentially and management involvement should only be necessary in cases of negligence or on the recommendation of the appointed check controller. The standards to be achieved and the check list of items to be evaluated should be made available to all those concerned. Member Associations should, together with their management, draw up a “code of conduct” which to the greatest possible extent will guarantee the objectivity and confidentiality of proficiency checks. A suitable period of evaluation should take place before a system of proficiency checks is implemented. Before a proficiency checking system is implemented, adequate training facilities should exist to enable further training to take place where necessary. (accepted as Guidance Material, Cairo 81.C.16-20) IFATCA is in support of a proficiency checking system for all air traffic controllers exercising the privileges of an ATC License or an equivalent Certificate of Competency for all qualified persons engaged in the duties of air traffic control. Before any proficiency checking system is implemented the respective Member Association and employer should undergo extensive negotiations and agree to resolve internal differences in respect of their own socioeconomic situation, (which includes retraining and job security). (Cairo 81.C.22) Member Associations should indicate to their employers that if assessments are conducted controllers must have the opportunity of sighting these assessments and discussing them with the assessing officer. Additionally a controller must have the opportunity of registering, on the assessment form, his comments regarding the assessment and the manner in which it was carried out. Where a proficiency checking system has been implemented, a controller who is selected to act in the Check Controller role should undergo a specialist course of training that will prepare him/her for the task, and provide guidance on achieving a fair, objective, and valid assessment. This training course should achieve consistency between check controllers. Additionally, a controller considered for the Check Controller role should have the following minimum experience:

Check Controllers should undergo the same periodic proficiency assessments as other controllers. This Assessor qualification should be the subject of periodic refresher training, at periods not exceeding 3 years, to ensure that skills are maintained and new techniques and procedures are incorporated. (Cancun 02.C.2) |

2.7.4 The policy itself is valid, but the terms used (proficiency checking; check controller) are outdated. Also, it lacks structure and does not include how often and in what way competence assessment should be performed.

2.7.5 References to collective bargaining and negotiations should be deleted from the policy as they are not part of competence assessment as a process – and thus outside the scope of this policy.

2.7.6 The current policy also mentions ‘negligence’ as a judgement that can be made by an assessor. PLC believes that this is a legal issue and outside the process of competence assessment. It is not up to an assessor to decide on potential negligence. There is extensive policy on Just Culture that addresses this matter.

2.7.7 The benefits of continuous assessment, as indicated by ICAO and Eurocontrol, should be adopted by IFATCA and thus be reflected in the policy.

2.8 Recorded data

2.8 The proficiency of controllers should be checked on-the-job in a live traffic environment, or in a simulator. The use of recorded data for competence assessment shall not be allowed. A situation where management or an assessor ‘pulls the tapes’ to judge a controller’s performance post hoc is unacceptable.

2.8.1 IFATCA has policy on the use of recorded data that addresses this issue. This text was last reviewed and updated in 2017:

| LM 11.2.6 USE OF RECORDED DATA IFATCA Policy is:

Audio and visual recordings and Ambient Workplace Recording (AWR), together with associated computer data and transcripts of air traffic control communications are intended to provide a record of such communications for use in the monitoring of air traffic control operations, and the investigation of incidents and accidents. Audio and visual recordings and AWR are confidential and shall not be released to the public. Audio and visual recordings and AWR shall not be used to provide direct evidence, such as in disciplinary cases, or to determine controller competence. |

Conclusions

3.1 Methods of assessing employees’ performance have evolved greatly in the last decades, from ‘finding flaws’ to a more holistic and integrated approach. In air traffic control, competency frameworks were developed for selection and training purposes, but they are now also used for performance assessment.

3.2 There are no clear legal prescriptions from ICAO on competence assessment for ATCOs. However, guidance is given by manuals from ICAO (DOC 10056) and Eurocontrol (Guidelines on Competence Assessment). They both emphasise the importance of competency-based training and assessment, and the importance of multiple observations (continuous assessment) instead of using a ‘snapshot’.

3.3 Competence assessment in ATC has an extra layer of difficulty because the ATCOs having the assessor role are in most cases, part of the active controller group – assessing their colleagues and each other. This can leave room for biases and personal conflict.

3.4 A survey conducted by IFATCA PLC last year revealed data on how competence assessment is implemented around the world. In most countries, an ATCO undergoes a practical simulator test once a year, or is observed while working a shift, together with an oral or written test on theoretical knowledge. In the African region, competence assessment is not yet common.

3.5 Generally all assessors are experienced ATCOs, who are carefully selected. There are great differences between countries in how assessors are kept current and if they are assessed themselves, after being installed in the position.

3.6 The survey also shows that while nobody likes being evaluated, most Member Associations have little problems with the way competence assessment is being carried out in their organisations. There is always room for improvement, for instance on the frequency of the assessments and the quality of the assessors.

3.6 IFATCA policy prohibits the use of recorded data for competence assessment. The proficiency of controllers should be checked on-the-job in a live traffic environment, or in a simulator. Also, competency assessment shall never be linked to remuneration.

3.7 The IFATCA policy on competence assessment originates from 1980 and has been reviewed and supplemented multiple times. Most of the policy is still valid, but it can be restructured and modernized. References to collective bargaining and determining controller negligence should be taken out of the policy, because these are processes outside of competence assessment.

Recommendations

The full proposed policy, to replace the current policy in TRNG 10.4.4, is:

TRNG 10.4.4 COMPETENCE ASSESSMENT

IFATCA is in support of competence assessment for personnel engaged in operational duties.

Theoretical knowledge and practical competence shall be assessed at least once a year, for every rating that a controller holds. The standards to be achieved and the check list of items to be evaluated should be made available to all those concerned.

IFATCA highly recommends the use of continuous assessment instead of pass/fail ‘snapshots’.

The results of competence assessments shall be treated confidentially.

Member Associations should, together with their management, draw up a “code of conduct” which to the greatest possible extent will guarantee the objectivity and confidentiality of competence assessments.

When assessments are conducted, controllers shall be able to view their results and to discuss them with the assessing officer. Additionally, a controller shall be able to record his comments, regarding the results and the manner in which the assessment was carried out.

Before a competence assessment system is implemented, the following, as a minimum, shall be taken into account:

– a suitable period of evaluation of the system should take place;

– adequate facilities to enable remedial training.

All ATCOs selected to act as assessors should undergo appropriate training that will provide guidance on achieving a fair, objective, and valid assessment.

Additionally, a controller considered for the assessor role should have the following as a minimum:

- 4 years operational experience;

- 1 year experience on the position where the assessment takes place;

- 2 years OJTI experience;

- having a high standard of credibility and communication skills in the OJTI/coaching role, and

- currency on the position where the assessment takes place.

Controllers having an assessor qualification shall be subject to the same competence assessments as other controllers.

The assessor’s qualification should be the subject of periodic refresher training, at periods not exceeding 3 years, to ensure that skills are maintained and new techniques and procedures are incorporated.

References

Cheetham, G., & Chivers, G. (1996). Towards a holistic model of professional competence. Journal of European industrial training, 20(5), 20-30.

European Aviation Safety Agency (2015). Technical requirements and administrative procedures related to Commission Regulation (EU) 2015/340. Consolidated version, issued August 2015.

European Organisation for the Safety of Air Navigation (2005). Guidelines for Competence Assessment. Eurocontrol Released issue number 2.0.

Hager, P., Gonczi, A., & Athanasou, J. (1994). General issues about assessment of competence. Assessment and evaluation in higher education, 19(1), 3-16.

International Civil Aviation Organisation (2011). Annex 1 to the Convention on International Civil Aviation: Personnel Licensing. Eleventh edition, July 2011.

International Civil Aviation Organisation (2016). Manual on Air Traffic Controller Competency-based Training and Assessment. First edition, 2016.

Madaus, G., & O’Dwyer, L. (1999). A Short History of Performance Assessment: Lessons Learned. The Phi Delta Kappan, 80(9), 688-695.

Moore, D. R., Cheng, M. I., & Dainty, A. R. (2002). Competence, competency and competencies: performance assessment in organisations. Work study, 51(6), 314-319.

Norcini, J., & Burch, V. (2007). Workplace-based assessment as an educational tool: AMEE Guide No. 31. Medical teacher, 29(9-10), 855-871.

Oprins, E., Burggraaff, E., & van Weerdenburg, H. (2006). Design of a competence-based assessment system for air traffic control training. The international journal of aviation psychology, 16(3), 297-320.