53RD ANNUAL CONFERENCE, Gran Canaria, Spain, 5-9 May 2014WP No. 157Written ELPPresented by PLC |

Summary

The ICAO Language Proficiency Requirements (LPRs) Technical Seminar, held in Montreal from the 25th to the 27th of March 2013, advanced the possibility to establish, in the near future, new language requirements affecting Air Traffic Controllers (ATCOs) and Pilots in order to manage the increasing use of Data-link and of its “free text” capability. The paper analyses the relationship between Data-link applications and English Language Proficiency (ELP) in order to evaluate the need for written ELP.

Introduction

1.1 In 1998, the ICAO Assembly, taking note of several accidents and incidents where the language proficiency of pilots and air traffic controllers were causal or contributory factors, formulated Assembly Resolution A32-16. Consequently, the ICAO Council was urged to direct the Air Navigation Commission to consider, with a high level of priority, the matter of English Language Proficiency (ELP) and to complete the task of strengthening the relevant provisions of Annexes 1 and 10, with a view to obligating contracting States to take steps to ensure that air traffic control personnel and flight crews involved in flight operations in airspace where the use of the English language is required are proficient in conducting and comprehending radiotelephony communications in the English language.

1.2 The objective of these requirements was to increase safety ensuring that pilots and ATCOs would have been able to communicate by voice without misunderstanding during daily operations and to deal with unusual situations such as emergencies, using both standard phraseology and plain English.

1.3 IFATCA has always been involved with this issue in order to provide information to MAs about the implementing process worldwide.

1.4 The first deadline for the compliance to the so-called “ICAO Operational Level 4” was the 5th March 2008. By that time every ICAO contracting State should have demonstrated a “Level 4” (at least) certification for all ATCOs and pilots operating in its airspace. This date was subsequently postponed to the 5th March 2011 but at this moment, there are only 73 compliant States out of 191.

1.5 Nevertheless, the increasing use of high technology systems is causing ICAO to consider the requirement for ATS personnel and pilots to be trained and tested both for their oral and written ELP, referring to the use of data-link.

Discussion

2.1 The ICAO Language Proficiency Requirements (LPRs) Technical Seminar, as shown in its official report, assigned the following issues to ICAO to consider, provided the work is determined a priority and that resources are available:

a) Language proficiency requirements for maintenance personnel; and

b) Consideration on whether reading and writing for free text in data link operations should be assessed.

2.2 ICAO

2.2.1 English Language Proficiency (ELP) is an issue affecting several ICAO publications, with a major impact on:

- Annex 1 – Personnel Licensing;

- Annex 6 – Operation of Aircraft;

- Annex 10 – Aeronautical Telecommunications;

- Annex 11 – Air Traffic Services;

- DOC 4444 – PANS ATM;

- DOC 9432 – Manual on Radiotelephony;

- DOC 9683 – Human Factors Training Manual;

- DOC 9835 – Manual on the Implementation of ICAO Language Proficiency Requirements;

- DOC 9859 – Safety Management Manual;

- Cir 318 – Language Testing Criteria for Global Harmonization;

- Cir 323 – Guidelines for Aviation English Training Programmes.

2.2.2 None of these publications makes reference to written English language proficiency. Annex 1 addresses current ICAO ELP provisions for only spoken verbal (oral) capabilities, requiring compliance with ICAO Operational Level 4 and with the following holistic descriptors:

a) Communicate effectively in voice-only (telephone/radio-telephone) and in face-to-face situations;

b) Communicate on common, concrete and work-related topics with accuracy and clarity;

c) Use appropriate communicative strategies to exchange messages and to recognize and resolve misunderstandings (e.g. to check, confirm, or clarify information) in a general or work related context;

d) Handle successfully and with relative ease the linguistic challenges presented by a complication or unexpected turn of events that occurs within the context of a routine work situation or communicative task with which they are otherwise familiar; and

e) Use a dialect or accent that is intelligible to the aeronautical community.

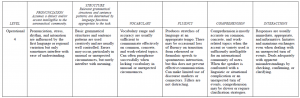

2.2.3 ICAO Operational Level 4 is the minimum grade of language proficiency acceptable to ensure safe operations and is characterized by specified pronunciation, structure, vocabulary, fluency, comprehension and interactions elements as shown in Figure 1 (taken from ICAO rating scale).

Figure 1

2.2.4 The introduction of new requirements on English Language Proficiency related to the training and testing of written capabilities would certainly require a revision on the mentioned publications. Written ELP should be accurately defined and new testing procedures would be needed.

2.3 IFATCA policy

2.3.1 IFATCA policy on English Language Training (page 4 2 3 24) is:

| Sufficient training must be available for current ATCOs of all English language abilities so as to be able to meet the required ICAO level and subsequently to retain (or improve) that competency.

Staff who are unable to achieve and maintain the English language requirements must have their positions protected and given opportunities to reach the required ICAO level. |

2.3.2 This statement would be still consistent even if ICAO decides to implement written ELP training and testing requirements. However section TRNG 3.6.1 – IFATCA Policy Document on Training, on page 4 2 3 44 of the IFATCA Technical and Professional Manual, paragraph addressed to English Language Training (Attachment A) broadly describes what ATCOs and Pilots should comply with, referring to “Level 4” and its parameters: pronunciation, structure, vocabulary, fluency, comprehension and interaction. This paragraph should be revised in case of new ELP requirements being introduced.

2.4 Data-Link applications

The ICAO Language Proficiency Requirements (LPRs) Technical Seminar assigned to ICAO to consider the possibility to assess writing and reading proficiency for free-text in data-link. ICAO DOC 9694 lists following data-link applications:

- DLIC (Data-Link Initiation Capability);

- ADS (Automatic Dependent Surveillance) ;

- CPDLC (Controller-Pilot Data Link Communications);

- DFIS (Data link Flight Information Services);

- AIDC (ATS Interfacility Data Communication) ;

- ADS-B (Automatic Dependent Surveillance – Broadcast).

2.4.1 DLIC (Data-Link Initiation Capability)

This application enables data link communications between airborne and ground systems, providing technical data that authorize the connection. The nature of the DLIC does not permit the use of free text messages; therefore, the issue assigned to ICAO by the Seminar does not affect it.

2.4.2 ADS

Automatic Dependent Surveillance is an application aimed to enhance surveillance services that permits position data to be transferred from aircraft to ground stations without the need and the possibility of free text messages. Accordingly, ADS is not affected by LPRs Technical Seminar’s consequences since it is not a means of communication but a surveillance system.

2.4.3 CPDLC

2.4.3.1 The ICAO Annex 10 – Aeronautical Telecommunications defines CPDLC as a means of communication between controller and pilot, using data-link for ATC communications.

2.4.3.2 CPDLC applications permit pilots and ATCOs to communicate electronically, using a set of elements corresponding to the voice phraseology used in ATC. This system is conceived to be used in conjunction with voice communication, especially for routine messages, to reduce frequency congestion.

2.4.3.3 Controllers are usually provided with the capability to respond to messages, to issue clearance, instructions and advisories, and to request and provide information. Pilots can respond to messages, request clearances and information, report information, and declare or cancel emergencies. Furthermore, in some cases, it is possible to produce “free text messages” (according to Annex 10), to allow them to exchange messages not conforming to defined formats. Each received message can be displayed and/or printed.

2.4.3.4 A single message can contain multiple elements that are either preformatted (standard) or composed using the “free text” capability. Free text elements (or messages) may be built using the IA5 (International Alphabet number 5) character set, consisting only of the following types: (0…9) (A…Z) (,) (.) (/) (-) (+) ( () () ) and the space character.

2.4.3.5 Despite the technical ability to compose elements and even sentences using characters and punctuation in order to communicate, theoretically, every possible message, this is discouraged by several aviation organisations due to the ambiguity related to written text. In oral communication, the meaning of the words and intonation play a fundamental role in the transmission of a message from the person originating it to the receiving one. The decoding process from words to information is affected by the receiving person’s expectations, both in verbal and in written communication; however, voice tonality has the ability to transmit concepts highlighting the correct shades of meaning. Written messages can be interpreted differently as a function of the two different interlocutors’ knowledge, of their attention, of their activities at that particular moment, of their different use of abbreviations, of the punctuation, etc.; every single alteration of these variables can cause dangerous misunderstandings. This prerogative, for example, contributes to the poetic charm of books, people read the content using their own feeling and previous experiences to build their own story. Whereas this written communication peculiarity can have catastrophic results in ATC, several international stakeholders discourage or, sometimes, even prohibit the use of CPDLC free-text capability.

2.4.3.6 In particular, ICAO DOC 4444 – ATM, and DOC 9694 indicate that concatenated messages shall be not too long (including five elements maximum) in order to avoid confusing the receiving person. Moreover, ICAO Annex 10 suggests (when considered necessary by the appropriate ATS authority) to set up additional pre-formatted free text messages to cope with situations not suitable for standard ones contained into PANS-ATM (DOC 4444), to reduce confusion related problems. These “new” elements shall be formulated in consultation with operators and other ATS authority, and properly published in AIPs.

2.4.3.7 Annex 10 and ICAO DOC 4444 discourage the use of free-text communications in order to prevent misunderstandings, suggesting front-line operators revert to voice communications to transfer non-standard messages or to clarify any doubt or ambiguity. ICAO DOC 4444, paragraph 14.1.4 reports that whenever textual presentation is required, the English language shall be displayed as a minimum. For this reason, according also to the EUROCAE (European Organisation for Civil Aviation Equipment) ED-110B recommendation on free-text, some aircraft manufactures and ACCs do not permit the use of this capability on their HMIs.

2.4.3.8 In Europe, EUROCONTROL is the organisation that has been mandated, in accordance with Article 8 of EC Regulation 549/2004, to develop requirements for the coordinated introduction of data link services. This regulation, by means of the EUROCONTROL document “ATC Data Link Operational Guidance in support of DLS Regulation No 29/2009”, provides some “pre-formatted” free-text messages to be used, in accordance with ICAO Annex 10, when elements contained in DOC 4444 Appendix 5 are not sufficient. Nevertheless, the same document specifies:

- Recommendation 8.3.8.1 – procedure design and training should reinforce that voice is the preferred option for complex dialogues (e.g. concatenated messages) or negotiations;

- Recommendation 8.3.9.1 – procedure design and training should include the fact that CPDLC shall only be used in the context of routine communications;

- Recommendation 8.3.9.2 – controllers should be trained on how to assess routine exchanges in the context of CPDLC;

- Recommendation 8.3.9.3 – procedure design and training should reinforce that voice is to be used for complex dialogues and negotiations.

2.4.3.9 According to the EUROCONTROL document, in Europe the implementation of CPDLC applications is intended to be a supplementary means of communication; voice is the primary communication method within the Region and CPLDC is not destined to replace it. Nevertheless, there are parts of the world, such as some oceanic areas, where CPDLC is used as primary means of communication due to radio frequency unavailability.

2.4.4 DFIS

This application is aimed to transfer flight related data from ground ATS units to aircraft (either point to point or via broadcast media), to enhance pilots’ situational awareness. Most of the information transmitted now via voice is expected to be transmitted via data link in the next future; these data may include:

- METAR service;

- Automatic Terminal Information service (ATIS);

- Wind shear advisory service;

- NOTAM service;

- Runway Visual Range (RVR) service;

- Aerodrome forecast (TAF) service;

- SIGMET service;

- Terminal weather service;

- Pilot report service;

- Precipitation map service;

- Terminal Aerodrome Forecast (TAF) service.

At the time, DOC 9694 – Manual of ATS data link applications includes requirements for ATIS and METAR service only ; the former makes no provision for free-text, while the second service allows the addition of free-text remarks modifying or expanding on METAR- coded weather elements.

2.4.5 AIDC

ATS Interfacility Data Communication is an ATC application for exchanging tactical control messages between ATS units, in order to permit:

- Flight notifications;

- Flight co-ordinations;

- Transfer of executive control;

- Transfer of communications; and

- Transfer of general information (flight data or free text messages).

2.4.5.1 It is not the intention that controllers see the messages, but their operational content is required to be displayed or made available to the controllers in accordance with the display capability and procedures at the unit concerned.

2.4.5.2 Free text messages can be sent in normal situations (free text general) or during emergencies (free text emergency), they shall only be used to transmit information for which any other message type is not appropriate, and for plain-language statements. Unlike what normally happens for all other messages, free text messages would be presented directly to the receiving controller, but this way of doing creates many Human Factor issues that need to be considered and assessed.

2.4.5.3 Analogously to the CPDLC, this application is a safety critical ATC tool; in fact, both systems allow the transfer of messages directly involved with the safe conduction of operations. In the opinion of PLC, AIDC free text messages can lead to the same unsafe situations highlighted for CPDLC messages, consequently front-line operators should preferably utilise voice communications (using telephones or face-to-face communication) to transfer complex or non-standard messages.

2.4.6 ADS-B

According to DOC 9694 (Manual of ATSs data link applications), Automatic Dependent Surveillance – Broadcast is an application which transfers parameters, such as position and identification, via a broadcast-mode data-link for utilization by any air and/or ground users requiring it. Similarly to ADS, ADS-B is a system that does not require and allow the use of free text messages because it is a surveillance system, with no relation to pilot- controller communication.

2.5 Phraseology

2.5.1 Several years ago, when experts analysed oral voice pilot-controller communications, they found that the complexity of messages should be controlled by implementing standard phraseology practices. Free text data-link messages reveal even more threats than voice ones, consequently, standard phraseology should be used to contribute to ease message understanding. It should be the same phraseology used for oral communication in order not to increase the complexity of the system.

2.6 Automation and free-text

2.6.1 Studies demonstrate that free-text messages are often used even when standard messages are available for the same scope. It has been demonstrated that operators (pilots and air traffic controllers) are sometimes tempted to compose free-text to save time because the menu structure of these systems’ interface is not always as intuitive as it should be. Training also plays a role in this decision making process, of course. This, in addition to the above considerations, does not allow ATC and on-board systems to automatically integrate these messages and, the requirement for operators to manually input all relevant data, increases complexity and the possibility of errors.

2.7 Future communication scenarios

2.7.1 At the moment, several projects around the world are studying how to improve pilot-controller communications within remote areas (oceans, deserts, polar areas, etc…), using different data and voice technologies such as satellites. Even the European region, where the EUROCONTROL document “ATC Data Link Operational Guidance in support of DLS Regulation No 29/2009” reports that “voice is the primary communication method within the Region and CPLDC is not destined to replace it”, is investing resources to ensure such technologies for future implementation. SESAR project P.15.2.4 – Future mobile Data Link system definition (within WP 15) is studying how to use Data-link as the primary means of communication, maintaining voice messages (assured by satellites) for emergency situations only. The project is a partnership between Airbus, Alenia, DFS, DSNA, EUROCONTROL, Frequentis, Indra, Honeywell, Noracon, Thales, AENA and ESA which expects to conclude the verification and validation phase by the end of 2016.

2.7.2 The importance of the project, the related investments and the partners involved put even more emphasis on the fact that any communication system evolution process in the aviation industry cannot ignore the subsistence of air-ground voice messages for emergency situations. Nevertheless, is opinion of PLC that every unusual situation should be handled via voice communication because it is recognised that free-text messages do not have the same flexibility and ability to solve or prevent potential misunderstandings in complex or non-standard situations that voice has. Every single misunderstanding or doubt can have catastrophic consequences in aviation, consequently voice communication should be guaranteed for all non-routine messages.

2.8 Future language proficiency scenarios

2.8.1 As seen the 62% of the ICAO States are still non-compliant to the existing English language proficiency requirements; some of them published are “partially” compliant, others not. These data are impressing because oral ELP is worldwide recognised to be fundamental for international aeronautical operations; nevertheless, economic, political, cultural and other reasons have played an important role in slowing down the implementation process. New language proficiency requirements might contribute to worsen the actual situation complicating the implementation process for those States that are now trying to reach the standards. An assessment on the on the real pros and cons of such new requirements should certainly be made.

Conclusions

3.1 Currently, ICAO does not mention written language proficiency in any published document, and has no provision on this issue.

3.2 IFATCA policy on ELP is consistent with this possibility but the training section of the Technical and Professional Manual should be reviewed if written ELP requirements are published.

3.3 Although ELP provisions are in force since 5th March 2008 (postponed to 5th March 2011), the 62% of the Chicago Convention’s signatory States are still non-compliant. Consequently, before publishing additional language requirements, an assessment on the expected benefit would be necessary to evaluate the possible safety increase in relation to the global situation at the moment.

3.4 ICAO publications discourage the use of CPDLC free-text messages, other than preformatted ones (Annex 10- Volume II §8.2.11, DOC 4444 §14.3.4), to prevent confusion related problems, while EUROCONTROL even recommends to train personnel to use free- text only for routine messages because voice is more suitable for complex transmissions or to adopt corrective or time-critical actions.

3.5 IFATCA agree with these positions and extends all related considerations to all affected data link applications (DFIS and AIDC) because it is known that free-text messages could cause (or contribute to) misunderstandings or doubts if used in non-routine situations. Data link is a silent medium. Its fixed message structure does not allow the flexibility that oral communication permits, moreover voice intonation can give additional meaning to messages avoiding or solving misunderstandings and doubts.

3.6 Despite this, IFATCA recognises that voice communications are not always available, especially to provide ANSs in remote or oceanic areas. Where, in such circumstances, controller or pilots are forced to use free-text messages, the application of standard phraseology would certainly facilitate the communication; however, the appropriate ATS authority should define a set of pre-formatted free-text messages, according to ICAO Annex 10, to reduce misunderstandings or doubt.

3.7 Where data-link would be the primary means of communication, the value of retaining voice transmissions for emergency messages is recognised as being of key importance within some of the ongoing projects relating to future operational scenarios. Moreover, PLC extends this value to all non-standard messages, considering the highlighted concerns related to written free-text, and considers voice communication fundamental for the transmission of non-routine messages.

Recommendations

It is recommended that:

4.1 IFATCA policy is:

Voice communication is fundamental for the transmission of non-routine messages.

4.2 IFATCA policy is:

Where data-link is available as a means of communication:

- A set of pre-formatted messages is necessary to minimise the need for ATCOs to compose free-text messages;

- ATCOs should revert to voice communication to transmit non-routine messages;

- Whenever possible, Standard phraseology should be used in composing free-text messages.

References

Report of the ICAO Language Proficiency Requirements Technical Seminar.

ICAO DOC 9835 – Manual on the implementation of ICAO Language Proficiency Requirements.

ICAO Annex 1 – Personnel Licensing.

ICAO Annex 10 – Aeronautical Telecommunications.

ICAO Annex 11- Air Traffic Services.

ICAO DOC 4444 – PANS ATM.

ICAO DOC 9694 – Manual of Air Traffic Services Data-Link Applications.

IFATCA Technical & Professional Manual.

EUROCONTROL ATC Data Link Operational Guidance in support of DLS Regulation No 29/2009.

EUROCAE ED-110B.

EC Regulation No 29/2009- laying down requirements on data link services for the Single European Sky.

SESAR P.15.2.4 presentation at the 3rd part resource meeting (Brussels, 28/11/2013).

FCI and P15.2.4 project presentation at the Iris information event (10/10/2011).

https://www.icao.int/safety/lpr/Pages/lpcompliance.aspx

Excerpt of “Human Factors Analysis of the RTCA SC-214/EUROCAE WG-78 Message Set”.

Attachment A

6.2. Additional Training

English Language Training

The ICAO requirements are that ATCOs and Pilots meet ‘Level 4’ standards of English competency, and these are broadly described below, but MAs should note that the terminology used is predominantly that of expert linguists and is not meant for operational ATCOs to necessarily understand.

The requirements became operative in 2003 for new recruits, but will be implemented in 2008 for current ATC Licence holders operating International Services:

Pronunciation

Pronunciation, stress, rhythm, and intonation are influenced by the first language or regional variation, but only sometimes interfere with ease of understanding.

Structure

Basic grammatical structures and sentence patterns are used creatively and are usually well controlled. Errors may occur, particularly in unusual or unexpected circumstances, but rarely interfere with meaning.

Vocabulary

Vocabulary range and accuracy are usually sufficient to communicate effectively on common, concrete, and work related topics. Can often paraphrase successfully when lacking vocabulary in unusual or unexpected circumstances.

Fluency

Produces stretches of language at an appropriate tempo. There may be occasional loss of fluency on transition from rehearsed or formulaic speech to spontaneous interaction, but this does not prevent effective communication. Can make limited use of discourse markers or connectors. Fillers are not distracting.

Comprehension

Comprehension is mostly accurate on common, concrete, and work related topics when the accent or variety used is sufficiently intelligible for an inter- national community of users. When the speaker is confronted with a linguis- tic or situational complication or unexpected turn of events, comprehension may be slower or require clarification strategies

Interactions

Responses are usually immediate, appropriate, and informative. Initiates and maintains exchanges even when dealing with an unexpected turn of events. Deals with apparent misunderstandings by checking, confirming or clarifying.

Sufficient training must be available for current ATCOs of all English language abilities so as to be able to meet the required ICAO level and subsequently to retain (or improve) that competency.

Staff who are unable to achieve and maintain the English language requirements must have their positions protected and given opportunities to reach the required ICAO level.