46TH ANNUAL CONFERENCE, Istanbul, Turkey, 16-20 April 2007WP No. 89Safety Management Policy Work PlanPresented by TOC |

Summary

As part of the work programme for 2006, the Technical and Operations Committee (TOC) was tasked with the review of the ICAO Safety Management Manual, Doc 9859. This document was produced as a collection of all the safety related information necessary for States to introduce a Safety Management System (SMS). It is a collaboration of many of the worlds leading experts in Safety. This working paper is an Air Traffic Control (ATC) orientated summary/analysis of ICAO Safety Management Manual, in which a cross-reference is made with the related IFATCA polices.

Introduction

1.1 ‘Safety Management’ is a phrase that is common place in many industries, not just in the aviation spectrum. Obviously safety in high profile industries such as ‘aviation’ has had immense media exposure both good and bad. Modern catastrophes have highlighted the fact that nothing can be left to chance, no accountability left un- challenged and indeed the responsibilities attributable through our judicial systems.

1.2 What we have seen happen in the evolution of our growing aviation industry is a major change of emphasis from just ‘being safe’ to ‘understanding and managing safety’. While safety has always been an overriding consideration, the past scenarios of just a compliance and regulatory regime (reactive) have now developed into a forward thinking (pro-active) approach. This takes the solid regulatory and legislative framework and combines it with a new transparent, scientifically analysed and culture driven safety system. This approach has now become the bearer of every decision made, every thought process acted on and indeed respected as the necessary culture to strive towards the future of Air Traffic Management (ATM).

1.3.1 ICAO has made significant grounds in this evolution, from the Chicago Convention in Articles 37 and 44 to where it currently stands with the proposed changes in 2005 to ICAO Annex 6, 11 and 14 in respect to harmonizing the provisions regarding safety management.

1.3.2 Part of this evolution is ICAO Safety Management Manual (SMM) Doc 9859. The purpose of this manual is to assist States in implementing the provisions of ICAO Operation of Aircraft Annex 6, ICAO Air Traffic Services Annex 11 and ICAO Aerodromes Annex 14 with respect to the implementation of safety management systems by operators and service providers.

1.4 This working paper will address those parts relating to ICAO Air Traffic Services Annex 11.

1.5 When reference is given to ‘the manual’ or ‘this manual’ it is directly referring to the SMM. When reference is given to ‘chapter’ it is referring to chapters contained within the manual.

Discussion

2.1 ICAO Air Traffic Services Annex 11 changes

2.1.1 In amendment 44, 23/11/06 to ICAO Air Traffic Services Annex 11, there are two key changes relating to safety. First, it defines two concepts: safety programs, aimed at States, and safety management systems, aimed at Air Navigation Services Providers (ANSPs). Second, the proposed harmonized provisions are generic in the sense that they are the same for Annexes 6, 11 and 14, except for domain-specific language. The term “safety management” is proposed as the title for the harmonized provisions in these Annexes. This term conveys the notion that managing safety is a managerial process that must be considered at the same level and along the same lines as any other managerial process. In order to reinforce the notion of safety management being a managerial process, the proposal includes a provision for an organization to establish lines of safety accountability throughout the organization, as well as at the senior management level. The proposal imposes upon States the responsibility to establish a safety program and, as part of such program, requires that operators, maintenance organizations and service providers implement a safety management system. The proposal furthermore places a requirement on States to establish an acceptable level of safety for the activities/provision of services under consideration.

2.1.2 IFATCA is in support of the proposed changes as can be found in the response to State Letter 2005/093e:

“IFATCA welcomes these proposals as positive steps and agrees with the need for clear guidance for States and operators regarding the regulation and implementation of aviation safety. Strict safety management in aviation is a necessity and the proposals included in Annexes 6, 11 and 14 will prove beneficial to this process.

IFATCA supports inclusions of references to accountability for safety on the part of senior management, as it has been our contention that the managerial process must include provisions for organizations to be accountable for safety at high levels. A commitment to safety starting from the highest levels is mandatory. To propose upon States the responsibility of establishing a safety program(s), which requires the implementation of safety management systems, and to place a requirement on States to establish an acceptable level of safety for the activities/provision of services is commendable. Our Federation has expressed concern with an apparent lack of safety concern by some States as witnessed by the use of unqualified air traffic controllers at several locations in recent memory. We are hopeful that “safety management” will convey the notion that managing safety is a responsibility of management that must be considered at the same level as any other managerial process. Hopeful these proposals will be a catalyst in addressing inter alia, these serious concerns.”

2.1.3 The ‘note(s)’ that are given on several occasions after the proposed amendments are very clear on the part that the SMM plays in establishing these new procedures. For example:

“Note — Guidance on safety programs and on defining acceptable levels of safety is contained in the ICAO Safety Management Manual (Doc 9859)”

2.1.4 As stated earlier, the purpose of the SMM is to support States with implementation of these new provisions. It has been based on ‘world’s best practise’ with the world’s leading experts on safety.

2.1.5 Application of this guidance material was never intended for the limited use of operational personnel but is relevant to the full spectrum of stakeholders in safety, including senior management.

2.1.6 This material, while very complex in nature, is aimed at those people who are responsible for the design, implementation and management of safety. Specifically;

a) Government officials with responsibilities for regulating the aviation system;

b) Management of operational organizations, such as operators, Air Traffic Service (ATS) providers, aerodromes and maintenance; and

c) Safety practitioners, such as safety managers and advisers.

2.1.7 The manual is not intended to be prescriptive but to provide philosophy, principles and practises for organisations to develop an approach to safety management.

The manual is not designed to be read from cover to cover but to help provide States with guidance at any particular stage, applicable to the State, in the implementation of their ’Safety Management System’.

As discussed earlier, the manual has been established with a broad range of potential audience members in mind. While ‘Safety Management’ has been a part of ATC operations for many years, it has not been in isolation and would be argued could not exist in isolation. It is, therefore, with careful appreciation we assess the information included in the manual.

2.2 Safety Management Manual Structure

2.2.1 The basic structure of the SMM is similar in design to many other reference manuals.

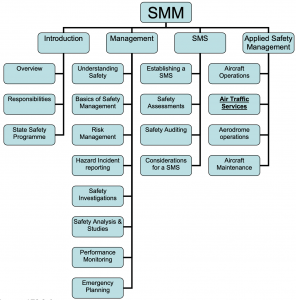

2.2.2 In part one it introduces the concept of ‘Safety’ and ‘Safety Management’ including the responsibility of ‘Managing Safety’ and the ‘State Safety Program’.

2.2.3 Part two is on ‘The Management of Safety’ and looks at the concepts of understanding safety; the basics of risk management; hazard and incident reporting; safety investigations; safety analysis and safety studies; safety performance monitoring and emergency response planning.

2.2.4 Part three looks at ‘Safety Management Systems’ and includes a detailed look at establishing these by safety assessments; safety auditing, and an in depth look at the ‘Practical Considerations for Operating a Safety management System’ which details the role of a ‘Safety Office’ and the training and promotion of safety information.

2.2.5 Part four is titled ‘Applied Safety Management’ and introduces specific detail in relation to industry specific needs. This includes aircraft operations; Air Traffic Services; aerodrome operations and aircraft maintenance.

2.2.6 The following diagram illustrates the basic structure of the manual. The underlined text under ‘Applied Safety Management’ is the chapter that is the primary focus of this working paper.

2.3 ATS Safety

2.3.1 General

2.3.1.1 Applying safety related principles in a dynamic ATC environment is a challenging prospect. The delicate balance of maximum traffic throughput with required safety, happens with the correct balance of human factors with automation and technology.

2.3.1.2 The ‘future capacity demand’ presents an enormous challenge for those associated with managing safety. This will be especially evident with the required changes to systems, procedures and technology essential to allow this increase. The complexity of ATC in the management of multiple runways and approach paths, environmental constraints, sovereign and international military requirements and the ever increasing demands of security of aircraft operations will only be managed with an increase in the capacity of managers, supervisors and line personnel to understand the human elements of safety and its application.

2.3.1.3 This can be further complicated by the changes to the way that States may structure themselves internally; this can include ‘corporatising’ the ATC business or managing airspace which is not sovereign to the country beneath it (Air Services Australia with Honiara; or the expected Functional Airspace Blocks (FABs) in Europe).

2.3.1.4 The business like approach taken by many ANSP’s has driven a desire for capacity increase. This desire for technological improvements to capacity has renewed interest in safety, understanding that without safety there is no ATC business. Likewise the ‘philosophy’ of managing the acceptable risk of this increased capability has also changed with a pro-active (not just regulatory driven) mindset in the application of safety.

2.3.1.5 Safety in ATS requires a systematic approach to safety management and today’s ATS systems provide multi-layered defences, through things as:

a) Rigid selection criteria and training for controllers;

b) Clearly defined performance standards, such as separation criteria;

c) Strict adherence to proven Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs);

d) Significant international co-operation;

e) Utilization of technological advances; and

f) Continuing system of evaluation, monitoring and improvement.

2.3.2 ICAO Requirements

2.3.2.1. ICAO Air Traffic Services Annex 11 requires that Air Traffic Service Providers (ATSPs) implement an approved safety management system to ensure safety in the provision of ATS. Such a safety management system shall ensure that actual and potential hazards can be identified, necessary remedial actions implemented and that continued monitoring ensures that an acceptable level of safety is being achieved.

2.3.2.2 ICAO PANS ATM Doc 4444 provides guidance for safety management in ATS. Inter alia, safety management in ATS should include the following:

a) Monitoring of overall safety levels and detection of any adverse trends;

1) Collection and evaluation of safety-related data;

2) Review of incident and other safety-related reports.

b) Safety reviews of ATS units;

1) Regulatory issues;

2) Operational and technical issues;

3) Licensing and training issues.

c) Safety assessments in respect of the planned implementation of airspace reorganization, the introduction of new equipment, systems, or facilities, and new or changed ATS procedures; and

d) Mechanisms for identifying the need for safety-enhancing measures.

2.3.3 Functions of the ATS regulatory authority

2.3.3.1 The State, as the signatory to the Chicago Convention, is responsible for implementation of ICAO Standards And Recommended Practices (SARPs) affecting flight operations, airspace and navigation services, and aerodromes for which it has responsibility. This responsibility may result in the formation of a “Civil Aviation Administration’ or similar. This ‘Regulatory Authority’ may adopt either an active role, involving close supervision of the functioning of all aviation related activities, or a passive role, whereby greater responsibility is delegated to the operators and service providers.

2.3.3.2 Considerable merit exists in a State regulatory system which falls between the active and passive extremes and which should:

a) Represent a well-balanced allocation of responsibility between the State and the operator or service provider for safety;

b) Be capable of economic justification within the resources of the State;

c) Enable the State to maintain continuing regulation and supervision of the activities of the operator or service provider without unduly inhibiting their effective direction and control of the organization; and

d) Result in the cultivation and maintenance of harmonious relationships between the State and the operators and service providers.

2.3.3.3 ICAO has placed a major emphasis on the global dissemination of safety related information, no longer is ‘safety management’ only a concern for the regulator of a State or the operators within its jurisdiction, but duplication of safety skills and initiatives and the information that may be developed needs to be shared with the global community. This is reflected in the conclusions from the “Directors General of Civil Aviation Conference on a Global Strategy for Aviation Safety, Montréal, 20 to 22 March 2006”:

“1. CONCLUSIONS

1.1 The Conference agreed on the following conclusions:

a) State and industry access to information and assistance

1) transparency is a cornerstone of aviation safety. All Contracting States and concerned stakeholders should cooperate to secure access to the information that is necessary to manage safety properly. Further improvements in aviation safety require an increased sharing of safety information among Contracting States, ICAO and all civil aviation stakeholders;

2) sharing of information among Contracting States is essential to maintain mutual trust; and

3) the implementation of a transparency policy by a State, with regards to its level of safety oversight, is a clear signal that the State acknowledges any weakness that may exist and should be an incentive for other States and donors to provide assistance.”

2.3.4 Safety Manager

2.3.4.1 In chapter 12 (Establishing a Safety Management System) we see a major emphasis on the accountability and responsibility of having a senior manager in the role as ‘Safety Manager’ (SM).

2.3.4.2 This manager should have direct responsibility (reporting) to the senior management team and be tasked with the sole responsibility of safety. This focal point becomes the driving force behind the organisational challenges in developing and managing an SMS. This Safety Manager would have direct reporting from the line management level, allowing for the efficient and accurate flow of information and tasking, appropriate to the organisational safety needs.

2.3.4.3 In large organisations this full time role (or department) plays a very active part in both the monitoring and developing of safety and safety initiatives. In smaller organisations however, this role may be shared with other responsibilities that a manager may have. This has to be carefully managed as a conflict of interest may apply if direct involvement in operational and/or technical matters (especially budgetary) lay within this framework.

2.3.4.4 Examples of items to be included in an ATS SM terms of reference include;

a) To develop, maintain and promote an effective safety management system;

b) To monitor the operation of the safety management system, and to report to the Chief Executive on the performance and effectiveness of the system;

c) To bring to senior management, any identified changes needed to maintain or improve safety;

d) To act as focal point for dealing with the safety regulatory authority;

e) To provide specialist advice and assistance regarding safety issues;

f) To develop a safety management awareness and understanding throughout the entire organisation; and

g) To act as a proactive focal point for safety issues.

2.4 ATS Safety Management Systems

2.4.1 Safety performance indicators and safety targets

2.4.1.1 Before deciding whether the safety performance of a system or a planned system change is acceptable, we must first establish ‘what is acceptable?’ Deciding this is the responsibility of the State.

2.4.1.2 ICAO Air Traffic Services Annex 11 requires States to establish an acceptable level of safety applicable to the provision of ATS within their airspace and at their aerodromes.

2.4.1.3 In order to determine what ‘an acceptable level of safety’ is, it is first necessary to decide on an appropriate safety performance indicator, and then to decide on what represents an acceptable outcome. The safety performance indicator chosen need to be appropriate for the application. Typical measures which could be used in safety management in ATS include:

a) Maximum probability of an undesirable event, such as collision, loss of separation or runway incursion;

b) Maximum number of incidents per 10,000 aircraft movements;

c) Maximum acceptable number of separation losses per 10,000 trans-Atlantic crossings; and

d) Maximum number of short-term conflict alerts (STCA) per 10,000 aircraft movements.

2.4.1.4 Safety indicators derived from the maximum number of accidents would not be a fair indication as these are rare events. What are to be investigated are the inherent factors of an ATC system that may be ‘ripe for an accident’. Often the incident rate(s) for many associated outcomes may be more useful indicators, understanding that the information gathered is only as good as the reporting systems that support this.

2.4.1.5 This is why the establishment of correct procedures in the collection and analysis of this vital information has been fully supported by IFATCA with a major emphasis on the establishment of a ‘just culture’. This is supported by further information in Chapter 4 (Understanding Safety) and the limitations on the use of this data from voluntary incident reporting systems in Chapter 7 (Hazard and Incident Reporting).

2.4.2 Risk Management

2.4.2.1 Risk management is defined as:

“The identification, analysis and elimination (and/or mitigation to an acceptable or tolerable level) of those hazards, as well as the subsequent risks that threaten the viability of an organization.”

2.4.2.2 The risk management process commences with the identification of hazards. These can be derived from many sources including system design, procedures and operating practices, communication, personnel and organizational factors, work environment etc.

2.4.2.3 In a mature safety management system, hazard identification should arise from a variety of sources as an on-going process. However, there are times as an organization that special attention to hazard identification is warranted. Safety assessments (Chapter 13) provide a structured and systemic process for hazard identification when:

a) There is an unexplained increase in safety-related events or safety infractions;

b) Major operational changes are planned, including changes to key personnel, or other major equipment or systems, etc.;

c) The organization is undergoing significant change, such as rapid growth or contraction; or

d) Corporate mergers, acquisition or downsizing is planned.

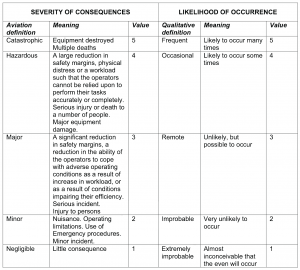

2.4.2.4 Risk assessment is the backbone of the analytical approach required to assess these hazards. This includes establishing the ‘probability of the hazard’, the ‘severity of the potential adverse consequences’ and the ‘rate of exposure to the hazard’. In other words it is the ‘loss potential’, established by the probability and severity of the potential outcome. This can be complex in its application both in the development of a matrix (to cross reference the probability and the severity of the hazard) and its consistent use.

2.4.2.5 Whatever methods are used, there are various ways by which risks may be expressed. For example:

a) Number of deaths, loss of revenue, or loss of market share (i.e..absolute numbers);

b) Loss rates (e.g. number of fatalities per 1,000,000 seat miles flown);

c) Probability of serious accidents (e.g. 1 every 50 years);

d) Severity of outcomes (for example, injury severity); and

e) Expected dollar value of losses vs. annual operating revenue (e.g. $1 million loss per $200 million revenue).

2.4.2.6 The risk acceptability will be determined by the resultant of the matrix (as referred to in paragraph 2.4.2.4 and see example below). This acceptability will then be managed by policy determined by the user. This may determine who can be responsible for this risk (line manager, centre manager or SM) this will also provide an accountability link for the process.

Based on: An Introduction to Flight Safety Risk Assessment (Paper by Richard Profit UK CAA)

2.4.2.7 Risk mitigation and controls may be used to lower the risk. This may be as simple as requiring training for staff before the implementation of a particular system or procedure, or may be as complex as a combined pilot/ATC education package in the change of a national airspace model. All of the existing controls and the mitigation strategies may lower the ‘acceptable risk’ understanding that there is no thing as ‘absolute safety’.

2.4.3 Incident Reporting Systems

2.4.3.1 ICAO PANS ATM Doc 4444 requires a formal incident reporting system for ATS personnel to facilitate the collection of information on actual or potential safety hazards or deficiencies related to the provision of ATS.

2.4.3.2 There are many different reporting systems that go to improve the overall safety of a system. These include:

- Mandatory incident reporting systems: These are where employees are required to report certain occurrences. This necessitates detailed regulation into what should be reported and how this will be done. Often resulting in “if in doubt – report it”.

- Voluntary incident reporting systems: ICAO Air Traffic Services Annex 11 recommends States introduce this type of reporting. This is where there may be an incentive to report, i.e. that no enforcement action be taken for unintentional violations that are reported.

- Confidential reporting systems: These systems aim to protect the individual reporting the incident. This is by de-identifying the person and returning any information that may have identified them, keeping no record of this. This information is often used to collect data on human error and can be used to serve the wider community by gaining insight into areas that otherwise may not have been known.

2.4.3.3 The philosophy of structured ‘reporting systems’ may certainly be a requirement for modern ATS safety systems, but to make these work effectively you need to have the following ingredients:

- Trust: This trust relates not only to voluntary reporting systems but also relates to mandatory. This trust comes in the form of a ‘fair and equitable’ approach to the management of these reports, allowing the ‘system’ to be trusted.

- Non-Punitive: This relies on being ‘confident in the confidence’ and knowing that there is structure in place to allow a ‘positive flow of negative information’.

- Inclusive reporting: While knowing one side of the story will give you some answers, knowing all sides of the story will give the investigator all the answers.

- Independence: Experience has shown that ‘voluntary reporting’ benefits from a trusted ‘third party’ managing this system. Away from the administration that is responsible for the enforcement of the regulations.

- Ease of reporting: The availability of forms and the simplicity in their detail, allowing for straightforward entry and completion.

- Acknowledgement: As they take time and honesty by the individuals reporting, they also require appropriate acknowledgement.

- Promotion: the information gathered in reporting systems needs to be for the wider community and must be promulgated appropriately and used to benefit others.

2.4.4 Emergency Response

2.4.4.1 ATS personnel must be prepared to continue to provide services through all circumstances including such events as after an accident, a power or communication failure and security threats etc. Emergency procedures must be in place to guide operations without further compromising safety. This requires an emergency response plan. This should be a collaborative plan between management and operational personnel who will have to execute it, in particular the controllers. Procedures must be in place and regularly tested to ensure the continued provision of services – perhaps at a degraded level.

2.4.5 Safety Investigations

2.4.5.1 When serious incidents or accidents occur, competent investigators are required to conduct the investigation. The more credible the investigator (due to technical and objectivity expertise) the better the outcomes will be. This is important because the information that is gathered will help in establishing the ‘why’ and the ‘how’ including identifying hazards and risks and the recommendations to possibly reduce or eliminate them. Good communication is also required in relaying these messages to the appropriate stakeholders.

2.4.5.2 For maximum effectiveness, management should focus on determining risks rather than identifying persons to discipline. How this is done will be influenced by the safety culture of the organization.

2.4.6 Safety oversight

2.4.6.1 In maintaining the safety standards of an ATS system, a system of monitoring and reporting must be established. This is often referred to as ‘safety oversight’. This includes all of the activities of controllers and supporting staff as well as the reliability and functionality of the systems that support them.

2.4.6.2 The objective of the safety oversight of ATS service providers is to verify compliance with relevant:

a) ICAO SARPs and procedures;

b) National legislation and regulations; and

c) National and international best practices.

2.4.6.3 This may include the use of audits and safety inspections. This will require these procedures to be standardized and documented to ensure consistent application.

2.4.6.4 Again, the process needs to be supported by well trained and knowledgeable staff. PANS-ATM Doc 4444 requires that qualified personnel have a full understanding of relevant procedures, practices and factors affecting human performance, conduct safety reviews of ATS units on a regular and systematic basis.

2.5 Changing ATS Procedures

2.5.1 ICAO PANS ATM Doc 4444 requires States to conduct a ‘safety assessment’ in respect to any proposals for significant changes to the provision of ATS. In the past this has included such changes as Required Vertical Separation Minimum (RVSM), Standard Arrival Routes (STARs) and Standard Instrument Departures (SIDs), re- sectorisation etc.

2.5.2 A safety assessment involves many experts from varied fields related to the change, identify hazards and make recommendations to lower the risk to an acceptable level. This could include the considerations to aircraft types, traffic density, route structure, radar coverage, cultural issues, communications etc.

2.5.3 The procedures described in Chapter 6 and 13 will cover this process and would involve the following:

a) Hazard identification (HAZID);

b) Hazard analysis, including likelihood of occurrence;

c) Consequence identification and analysis; and

d) Assessment against risk criteria.

2.5.4 When management proposes to develop, validate, change or introduce operational procedures, where practicable they should:

a) Utilize hazard identification, risk assessment and risk management techniques prior to introduction of the procedure;

b) Use simulation to develop and evaluate new procedures;

c) Implement changes in small, easily manageable steps to allow confidence to be gained that the procedures are suitable; and

d) Commence changes in periods of low traffic density.

2.6 Threat and Error Management

2.6.1 Threat and Error Management (TEM) is the understanding of the inter-relationship between safety and human performance in dynamic and challenging operational contexts. While the concept of ‘threats’ have long been recognized, the principles of TEM make it possible to manage the three basic components of TEM: threats, errors and undesirable states.

2.6.2 Threats, errors and undesired states have to be managed by ATC everyday. These include dealing with adverse weather conditions; terrain issues; aircraft malfunctions etc. The understanding of these threats and errors allows for the fine margins needed in ATC to be managed.

2.6.3 Normal Operations Safety Survey (NOSS) has been developed for ATC it has been derived from the successful Line Operations Safety Audit (LOSA) program introduced by the airlines. It is a way of gathering data in relation to these threats and errors that doesn’t rely on the individual reporting it.

2.6.4 The idea behind NOSS is to provide the ATC community with a means for obtaining robust data on threats, errors and undesired states. Analysis of NOSS data, together with safety data from conventional sources, should make it possible to focus the safety change process on the areas that need attention the most.

2.6.5 NOSS involves over-the-shoulder observations during normal shifts. Analysis of this normative data in conjunction with data acquired through other means (such as incident reporting schemes, occurrence investigations, etc.) should provide ATC management with a means for focusing the safety change process on those threats that most erode the margins of safety in the ATC system.

2.7 IFATCA Policy

2.7.1 Safety Management Systems

2.7.1.1

| “IFATCA supports the introduction of Safety Management Systems (SMS) for the purpose of ensuring a systematic approach to the reduction of risk within the ATM system.

ATM providers should be encouraged from the outset to utilise the available operational expertise already existing within their organisations when developing SMS. ATM providers should make available training in safety related subjects such as hazard analysis and risk assessment for selected operational personnel to maximise the effectiveness of the SMS processes.” |

2.7.1.2

| “IFATCA supports the introduction of Safety Management Systems (SMS) for the purpose of ensuring a systematic approach to the reduction of risk within the ATM system.” |

This IFATCA policy is well supported within the SMM. This is in reference to ICAO Air Traffic Services Annex 11 and refers to the following (ICAO Air Traffic Services Annex 11, 2.26 Safety Management):

“2.26.3 States shall require, as part of their safety programme, that an air traffic services provider implements a safety management system acceptable to the State that as a minimum:

a) identifies safety hazards

b) ensure that remedial action necessary to maintain an acceptable level of safety is implemented

c) provide for continuous monitoring and regular assessment of the safety level achieved

d) aims to make continuous improvement to the overall level of safety.”

This policy is therefore recommended for deletion.

2.7.1.3

| “ATM providers should be encouraged from the outset to utilise the available operational expertise already existing within their organisations when developing SMS.” |

This paragraph is not supported in ICAO Air Traffic Services Annex 11, ICAO PANS- ATM Doc 4444 or the SMM, while there is some mention of professional expertise in relation to identifying and ameliorating safety hazards, no where is it prescriptive as to who should be involved in the development of the SMS.

More importantly the issue of ‘current’ and ‘relevant’ experience needs to be addressed in the selection of operational expertise. Selecting people with current operational experience brings credibility and experience to the individual safety management process.

SMM Doc 9859 – Chapter 2, pages 2-6:

“In a similar manner, professional associations representing the interests of various professional groups (e.g. pilots, air traffic controllers, flight attendants, etc.) are active in the pursuit of safety management. Through studies, analysis and advocacy, such groups provide subject matter expertise for identifying and ameliorating safety hazards.”

The policy is therefore recommended to be amended to include “and current”.

2.7.1.4

| “ATM providers should make available training in safety related subjects such as hazard analysis and risk assessment for selected operational personnel to maximise the effectiveness of the SMS processes.” |

This paragraph is supported by the SMM.

SMM Doc 9859 – Chapter 15, pages 12-15:

“In addition to the corporate indoctrination outlined above, personal engaged directly in flight operations (flight crews, controllers, maintenance technicians, etc.) will require more specific safety training with respect to:

a) Procedures for reporting accidents and incidents;

b) Unique hazards facing operational personnel;

c) Procedures for hazard reporting;

d) Specific safety initiatives, such as:

1) Flight Data Analysis (FDA) programme;

2) LOSA programme;

3) NOSS programme;

e) Safety committee(s);

f) Seasonal safety hazards and procedures (winter operations, etc.);

g) Emergency procedures.”

This policy is therefore recommended for deletion.

2.7.2 Air Safety Reporting Systems

2.7.2.1 IFATCA Policy is:

|

“MAs should promote the creation of Air Safety Reporting systems based on Confidential reporting in a just culture among their service provider(s), Civil Aviation Administration and members. IFATCA shall not encourage MAs to join Incident Reporting Systems unless provisions exists that adequately protects all persons involved in the reporting, collection and/or analysis of safety-related information in aviation. Any incident reporting system shall be based on the following principles: a) in accordance and in co-operation with pilots, air traffic controllers and Air Navigation Service Providers; b) the whole procedure shall be confidential, which shall be guaranteed by law; c) adequate protection for those involved, the provision of which, be within the remit of an independent body.” |

2.7.2.2 Through several different chapters in the SMM reference is made to non-punitive reporting. In chapter seven it details the issues regarding an accurate and relevant reporting system. This includes elements such as trust and the involvement of employees in the establishment of reporting systems. Many references are made to a ‘just culture’ and in chapter four it is given as an example of ‘a positive safety culture’. IATA did a ‘Non Punitive Policy Survey’ in 2002 and the manual discusses these findings:

SMM Doc 9859 – Chapter 4, pages 4-20:

“While many aviation operations are taking this positive approach to the management of safety, others have been slow to adopt and implement effective ‘non-punitive policies’. Others have been slow to extend their non-punitive policies on a corporate wide-basis.”

2.7.2.3 For many years IFATCA has been ‘championing the cause’ to have safety management responsibility bestowed upon senior management and to produce a ‘hand-in-glove’ arrangement that allows associations (representing the professional needs of ATC) to play an active part in creating the safety culture necessary to form a ‘pro-active’ modern safety management system.

2.7.2.4 While ICAO recommends the introduction of a ‘just-culture’ we have seen many of the implementations not realise their potential. IFATCA has welcomed the increased support by some ANSP’s in forging this ‘just-culture’, but understands the need to reinforce why it has become essential, the following press release was written in support of the decision taken by the Provisional Council of Eurocontrol to strengthen and improve the “Just Culture” approach in safety reporting in aviation.

IFATCA Press Release

November 12th 2005

“In order to be able to guarantee a sustainable growth of aviation while improving safety and reducing the risk of incidents and accidents the aviation industry must learn valuable lessons, re-think its methods of doing business and move beyond a blame culture that singles out individuals and criminalizes error(s). With a cloud of legal liability hanging over system operators, progress in the quest for true system safety is in jeopardy. Accidents and incidents are not caused by individuals, but by many contributing factors. Focusing blame on system components (operators) is not the correct way to improving aviation safety, and is, in fact, counter-productive as it stifles the reporting process. A just culture, free from the threat of punishment is needed to ensure comprehensive and systematic safety occurrence reporting.”

2.7.2.5 While having reference to ‘just culture’ and indeed the benefits listed in the SMM, the current policy by IFATCA is laid out to protect the confidentiality and the need for the procedures to be ‘guaranteed by law’. This is a very important consideration and one that is certainly still required. This is further reinforced by the poor take-up of these mandates by certain ANSP’s and the lack of guaranteed confidentiality and protection of the controllers involved.

This policy is under review by a separate paper (C.6.2).

2.7.3 Normal Operations Safety Survey (NOSS)

2.7.3.1 IFATCA Policy is:

| “Monitoring Safety in Normal Operations must be seen as an integral element of a Safety Management System. A safety tool such as NOSS, shall meet following conditions:

|

2.7.3.2 While NOSS is only new in its implementation (first operational data gathering completed in 2006 in Australia by AirServices Australia, report yet to be completed). The concept is a proven one; it has been used in the airline industry (LOSA) successfully and provides useful normative data for the analysis of aviation operations.

2.7.3.3 At the time that the SMM was written (and at present) an ICAO NOSS Manual is yet to be formally produced. The time frame for NOSS SG was late 2006; there has been significant work done on this manual and a second draft has been completed. The draft ICAO circular contains some information about NOSS. The information contained within the SMM is in line with IFATCA policy and it is expected that the NOSS Manual will be as well.

The policy is recommended to be retained until the NOSS manual is produced.

Conclusions

3.1 The SMM is a comprehensive document written by experts in safety. It has been written for all stakeholders in safety, with information on the philosophy and design of modern safety systems. It is not meant to be prescriptive, but meant to be a valuable resource accessible to strengthen existing procedures; to cross check current practice and encourage the development of further elements of a safety system.

3.2 Changes to several of the ICAO Annexes have streamlined the approach to safety management, allowing consistent methodology across the different fields. This has also allowed the SMM to be consistent in it’s referencing within this redefined strategy.

3.3 Chapter 17 of the SMM details the specific application of safety management in the ATS environment. This includes information on the ICAO requirements and the State regulatory authority; the role that a safety manager should have within the organisation; defining performance indicators and safety targets; the risk management process, safety investigations and incident reporting systems; changing ATS procedures; the TEM strategies and NOSS.

3.4 In review of current IFATCA policy, the SMM supports many of the ideals and strategies that have been placed in the IFATCA Manual over the last few years. While most of the current IFATCA policy may be supported by the SMM, ICAO PANS-ATM Doc 4444 and the changes to ICAO Air Traffic Services Annex 11; not all of the policy intent is covered. This will result in part of the policy being eligible for deletion but more importantly the need for policy to be amended.

Recommendations

4.1 IFATCA policy on page 4 1 7 1 of the IFATCA Manual:

“IFATCA supports the introduction of Safety Management Systems (SMS) for the purpose of ensuring a systematic approach to the reduction of risk within the ATM system.

ATM providers should be encouraged from the outset to utilise the available operational expertise already existing within their organisations when developing SMS.

ATM providers should make available training in safety related subjects such as hazard analysis and risk assessment for selected operational personnel to maximise the effectiveness of the SMS processes.”

is deleted.

4.2 IFATCA Policy is:

“Air Traffic Service Providers (ATSPs) should be encouraged from the outset to utilise the available and current operational expertise already existing within their organisations when developing SMS.”

and is included in the IFATCA Manual on page 4 1 7 1.

References

ICAO Safety Management Manual Doc 9859 An/460.

ICAO Air Traffic Services Annex 11 – Air Traffic Services.

ICAO State Letter 2005/093e.

IFATCA response to ICAO 2005/093e.

IFATCA Technical and Professional Manual.

ICAO PANS-ATM Doc 4444.

ICAO Directors General of Civil Aviation Conference on a Global Strategy for Aviation Safety, Montréal, 20 to 22 March 2006 Recommendations and Conclusions.

IFATCA Press Release November 12th 2005 ‘Just Culture’.

Note: Much of the content within this working paper has been adapted from the ‘ICAO Safety Management Manual Doc 9859 An/460’.