50TH ANNUAL CONFERENCE, Amman, Jordan, 11-15 April 2011WP No. 88Environment – Study Emission TradingPresented by TOC |

Summary

This paper explains the concept of an Emission Trading System (ETS), a system developed to reduce the emission of greenhouse gasses and discusses if there could be any operational impact of the system on the workload of ATCOs when introduced within the European Union or elsewhere.

This working paper is intended as information material, and does not recommend IFATCA Policy.

Introduction

1.1 Countries with commitments under the Kyoto Protocol have accepted targets for limiting or reducing emissions. These targets are expressed as levels of allowed emissions, or “assigned amounts,” over the 2008-2012 commitment period. The allowed emissions are divided into “assigned amount units”.

1.2 Emissions trading, as set out in the Kyoto Protocol, allows countries or organizations that have spare emission units (emissions permitted to them but not “used”) to sell this excess capacity to countries or organizations that are over their targets. Thus, a new commerce was created in the form of the trading in emission reductions or removals. Since carbon dioxide is the major greenhouse gas, people speak simply of trading in carbon. Carbon is now tracked and traded like any other commodity. This is known as the “carbon market.”

1.3 The Technical and Operational Committee was tasked with investigating Emission Trading and studying if there are operational consequences when introducing an Emission Trading System (ETS) in aviation. The European Union is planning to introduce the system in aviation in 2012.

Discussion

2.1 What is “Emissions Trading”?

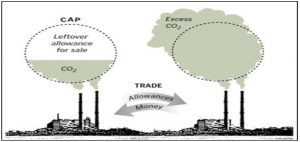

A limit is allocated or sold to companies in the form of an emission allowance, which represents the right to emit a specific volume of a specified pollutant. Companies are required to hold a number of allowances equivalent to their emissions. The total number of allowances cannot exceed the cap, limiting total emissions to that level. Companies that need to increase their emission allowances must buy allowances from those who require fewer allowances. The transfer of allowances is referred to as a trade. In effect, the buyer is paying a charge for polluting, while the seller is being rewarded for having reduced emissions. Thus, in theory, those who can reduce emissions most cheaply will do so, achieving the pollution reduction at the lowest cost to society.

2.2 What is an “Emissions Trading System” (ETS)?

ETS is a trading system, which allows an organisation to decide how and where they will reduce emissions by trading their emissions allowances. This ensures emissions are reduced where the cost of reduction is lowest. The cost of emissions allowances is determined by the “carbon market”, the intersection of demand for, and availability of, allowances.

Such a system is suited to greenhouse gases, as these have the same effect wherever (globally) they are emitted. It enables States to establish overall caps on emissions but still provides companies with the flexibility to exceed limits. It also provides financial incentives to invest in low carbon technologies.

2.2.1 In January 2005 the European Union Greenhouse Gas Emission Trading System (EU ETS) commenced operation as the largest multi-country, multi-sector Greenhouse Gas Emission Trading System. The system is based on Directive 2003/87/EC, which entered into force on 25 October 2003. To include aviation into the EU Emissions Trading System (ETS) Directive 2008/101/EC was published on 13 January 2009.

2.2.2 Since this Directive 2008/202/EC has introduced aviation into the EU ETS, the 30 European Economic Free Trade Area (EFTA) States have now decided to include aviation into the legislation within the European Economic Area (EEA).

According to the Directive, EU ETS will cover the following additional EEA EFTA flights:

- Domestic flights within the EEA of EFTA States;

- Flights between the EEA of EFTA States;

- Flights between the EEA of EFTA States and countries outside the EEA (third countries).

As a result, the EU ETS will affect all aircraft operators performing flights to and from EEA countries.

The following flights are exempted from the EU ETS:

- VFR and military flights

- Training flights and flights for maintenance reasons

- Commercial flights if <10‘000 t CO2 / y or < 243 flights in 3 consecutive periods of 4 months

2.2.3 Key features of the EU ETS:

- Total quantity of emission allowances allocated to operators equivalent to 97% (2012) and 95 % (from 2013 onward) of historical aviation emissions (this percentage may be reviewed as part of the general review of the Directive).

- Historical aviation emissions = mean average of the annual emissions in the calendar years 2004, 2005 and 2006 from aircraft performing an aviation activity listed in Annex I of the Directive.

- 15% of the available allowances shall be auctioned (percentage may be increased as part of the general review of the Directive).

2.2.4 The intention for the EU ETS is to serve as a model for other countries considering similar national or regional schemes, and to link these to the EU scheme over time. Therefore, the EU ETS is intended to form the basis for wider, global action.

2.3 ICAO

2.3.1 The 33rd ICAO Assembly (2001) endorsed the “development of an open emissions trading system for international aviation” and:

“requested the Council to develop as a matter of priority the guidelines for open emissions trading for international aviation, focusing on establishing the structural and legal basis for aviation’s participation in an open trading system, and including key elements such as reporting, monitoring, and compliance, while providing flexibility to the maximum extent possible consistent with the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) process.”

2.3.2 Subsequently, at its 35th Assembly (2004), ICAO endorsed the “further development of an open emissions trading system for international aviation” and requested the Council, in its further work on this subject, to focus on two approaches, namely to:

“support the development of a voluntary trading system that interested Contracting States and international organizations might propose” and to “provide guidance for use by Contracting States, as appropriate, to incorporate emissions from international aviation into Contracting States’ emissions trading schemes consistent with the UNFCCC process”.

Under both approaches, the Council was instructed to ensure that the guidelines for an open emissions trading system address the structural and legal basis for aviation’s participation in an open emissions trading system, including for example key elements such as reporting, monitoring and compliance.

2.3.3 Assembly Resolution A36-22 (2007):

The Assembly Declares that ICAO, as the lead United Nations Agency in matters involving international civil aviation, is conscious of and will continue to address the adverse environmental impacts that may be related to civil aviation activity and acknowledges its responsibility and that of its Contracting States to achieve maximum compatibility between the safe and orderly development of civil aviation and the quality of the environment. In carrying out its responsibilities, ICAO and its Contracting States will strive to:

a) limit or reduce the number of people affected by significant aircraft noise;

b) limit or reduce the impact of aviation emissions on local air quality; and

c) limit or reduce the impact of aviation greenhouse gas emissions on the global climate.

2.3.4 ICAO Committee on Aviation Environmental Protection (CAEP) has addressed the subject of ETS extensively. Furthermore CAEP has conducted a considerable number of workshops and studies on the subject of ETS.

2.3.5 ICAO has published guidance material Doc 9885 Guidance on the Use of Emission Trading for Aviation. The Manual provides extensive information on the subject of Emissions Trading; nevertheless the Manual does not address ATM operations within the implementation of an ETS.

2.3.5.1 ICAO Doc 9885 provides guidance on the implementation of an ETS regarding international aviation (paragraph 3.2.35):

“States that wish to incorporate emissions from international aviation into their emissions trading schemes consistent with ICAO A36-224 (Appendix L) should not implement an emissions trading system on other Contracting States’ aircraft operators except on the basis of mutual agreement between those States.”

2.3.5.2 The intention of the EU, according to Directive 2008/202/EC, is to also impose the EU ETS on aircraft operators of other Contracting States without a mutual agreement between the EU and those other States. Thereby it appears that the European Union ignores the ICAO guidance in Doc 9885 paragraph 3.2.35 in regard to the implementation of the EU ETS.

2.3.6 In October 2010 ICAO stated:

“Additional new initiatives include the development of a framework for Market-Based Measures (MBMs), a feasibility study on the creation of a global MBM scheme an guiding principles for States to use when designing and implementing market-base measures for international aviation.”

Thereafter the European Union claimed the way clear for its plan to include aviation in the EU ETS from 2012. According to Reuters the European Commission said:

“ICAO has refrained from language which would make the application of the EU’s ETS to their airlines dependent on the mutual agreement of other states.”

The Air Transport Association, representing US airlines opposed to inclusion in the EU ETS, disputed the EU Commission’s interpretation of ICAO’s statement. It said the majority of countries approved mutual agreement on ETS inclusion and emphasized that ICAO is non-binding on member states.

2.3.7 The US airline industry started a lawsuit to challenge the legality of the plan of the European Union to apply the ETS to non-EU airlines. The English High Court referred the case in May 2010 to the European Court of Justice in Luxembourg.

2.4 Relevant IFATCA Policy [ATS 3.25]:

| “In case environmentally driven procedures are introduced in the ATM System, these must be introduced taking into consideration the increased complexity for the controller. This complexity must be managed at the appropriate, strategic, level. A trade off between environment and capacity must be considered as part of this management of complexity, as safety is paramount.” |

2.4.1 Taking the IFATCA Policy on environmentally driven procedures in consideration, TOC is of the opinion that the implementation of an ETS (although no operational procedure) in aviation should result in a system that has no operational impact on the workload of ATCOs.

2.4.2 IFATCA’s Statement on Future ATM:

“Each member of the ATM community is individually responsible for behaving in an environmentally responsible manner” and “…the combination of all ATM activities is a community activity and there will be a level of shared commitment, collaboratively agreed, to the ATM system operating in an environmentally sustainable way.”

This statement does not imply that IFATCA opposes the introduction of an ETS in aviation.

2.5 Airlines are often required to fly longer distances solely for noise abatement, thereby burn more fuel and increase their aircraft emissions. Extended taxi distances to reach noise-friendly runways also require increased fuel consumption. Airlines might end up shouldering the burden of conflicting environmental demands. The Environment Case, mentioned in Working Paper B.5.1 “Study Environment Case”, could give insight into these conflicting environmental demands.

2.5.1 It is yet uncertain what the strategy and behaviour of the airlines will be to cope with ETS. Nowadays the airlines can put time as a priority over fuel efficiency. The outcome could be that airlines will change the way of operation, which could have an unknown side effect on ATM. Aircraft could fly routinely slower speeds due to fuel efficiency, and flight schedules could be subjected to change due to the modified priority of the airlines. This could change the operations at aerodromes. Before implementing ETS it could be beneficial to study these possible side effects in ATM.

2.5.2 Airlines unable to comply with the determined allowances or those wanting to make profit from the sale of allowances could pressure ANSPs (or ATCOs directly by pilots) to provide shorter flight- times. The method used to track the use of emissions allowances could ultimately have an operational impact on controller workload. According to IFATCA Policy, this must be prevented.

2.5.3 A possible solution could be to impose charges based on shortest possible routing from departure to destination, not based on actually travelled distance or actual fuel consumption. This approach would provide a system without being influenced through unexpected factors (weather, emergencies, etc.), which could lead to increased emissions and over which the airlines have no control. However TOC does acknowledge the fact that such a system would not be based on the actual amount of emissions. With regard to ETS, TOC also considers aviation to be unique as compared to any other industry. Aviation could very well require a different kind of ETS for safety and operational reasons.

2.6 Environmental constrains and charges often negatively influence local or national economies. TOC considers ETS to be an environmental tax, and in this context it would be better to implement ETS globally to avoid negative regional economical effects.

2.6.1 Several years ago an environmental tax in The Netherlands, imposed on airlines on international flights, was passed through to the passengers. This caused huge numbers of Dutch passengers to fly out of aerodromes just over the Dutch country borders to avoid the increased airfares. They also flew from abroad back to Amsterdam to continue from there to the intended destination. The result was a financial misfortune to Amsterdam Schiphol and the national economy. The intent of this environmental tax – to reduce the emission of greenhouse gases – was poorly served because passengers just crossed the national borders to avoid increased ticket prices. Regardless of the tax, global emission of greenhouse gases remained the same, or even increased, which made it clearly a self-defeating tax.

Conclusions

3.1 ETS could serve as a cost-effective measure to limit or reduce greenhouse gasses emitted by civil aviation in the long term. ETS permits compliance flexibility, allowing stakeholders to make a tailored choice in order to meet their target limit for emissions.

3.2 ICAO supports the implementation of an ETS in aviation. According to ICAO, guidelines for an ETS should address the structural and legal basis for aviation’s participation in an open ETS, including key elements like reporting, monitoring and compliance. Although ICAO CAEP has addressed the subject extensively (Doc 9885), ICAO provides only options, and no actual guidelines, how to practically implement an ETS in aviation.

3.3 In regard of IFATCA’s Statement on the Future of Global ATM, IFATCA does not oppose the implementation of an ETS in aviation.

3.4 An ETS could have an operational impact on controller workload. TOC stresses the need for further study on the behaviour of airlines towards ETS to prevent unforeseen side effects in ATM.

3.5 IFATCA Policy does cover any operational effects of the implementation of an ETS.

Recommendations

It is recommended that;

4.1. This paper is accepted as information material.

References

ICAO Doc 9885 Guidance on the Use of Emissions Trading for Aviation.

ICAO Assembly Resolution A33-7 (2001).

ICAO Assembly Resolution A35-5 (2004).

ICAO Assembly Resolution A36-22 (2007).

ICAO Report of Voluntary Emissions Trading for Aviation.

Wikipedia – Emissions Trading.

European Union Directive 2008/202/EC.

European Commission https://ec.europa.eu/environment