DISCLAIMER

The draft recommendations contained herein were preliminary drafts submitted for discussion purposes only and do not constitute final determinations. They have been subject to modification, substitution, or rejection and may not reflect the adopted positions of IFATCA. For the most current version of all official policies, including the identification of any documents that have been superseded or amended, please refer to the IFATCA Technical and Professional Manual (TPM).

61ST ANNUAL CONFERENCE, 23-27 May 2022WP No. 82Military to Civilian Licence ConversionPresented by PLC |

Summary

Military air traffic controllers leaving the military service to commence work in civilian Air Traffic Control (ATC) often have no recognition of their ATC experience or qualifications. This can result in military air traffic controllers having to undertake an initial training course with the associated length of time and cost. This paper looks at what the barriers of converting military qualifications to a civilian air traffic control licence are and what methods are available today and might be available in the future.

Introduction

1.1. There are service men and women leaving the military who potentially have lots of experience in the air traffic control (ATC) profession. Military Air Traffic Control Officers (ATCOs) have to complete an initial training course with their military organisation. When looking to enter civilian ATC, this previous experience could allow for reduced training times by removing topics that have already been taught. More often than not however this does not happen. Military ATCOs, looking to transfer into civilian ATC are often required to complete the full initial training course as an ab-initio.

1.2. A rising problem in civil aviation is the scarcity of air traffic controllers. To combat this, Air Navigation Service Providers (ANSPs) like NATS in the UK, are initiating recruitment drives [1]. The impact of these shortages within Europe [2] and around the world can cause serious travel disruption, often in peak times.

1.3. The ability to train ATCOs quickly could go some way to meeting this shortfall. With training times of 2-3 years, there is a push from bodies [3] within Europe to reduce the time it takes to train an ATCO. Military ATCOs having to commence their training from the beginning, relearning topics and practices they have already covered before is time that could be saved. Recognising military qualifications and skills could enable training times to be reduced or eliminated.

1.4. To understand the reasons behind the current situation, this paper looks at the licensing regulations in the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) and the European Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) and investigates what happens in states around the world.

Discussion

2.1. Military ATCO licences, when issued, do not have to comply with ICAO or EASA standards as these standards are for civilian air traffic control. They do however operate in accordance with state requirements and military orders. However, if a state chooses to, it can apply these standards to military ATCOs who provide services to the public [4]. In the UK for example, military ATCOs hold “Certificates of Competency” which do not conform to ICAO or EASA standards. Also, airports like Northolt are controlled by military ATCOs who will often provide services to civilian air traffic.

2.2. Not having a licence endorsed by EASA or ICAO will require military air traffic controllers, on leaving the military, to convert their licence to either an ICAO or an EASA compliant licence before they can continue their career in civilian ATC.

2.3. Military and civilian controllers can often work alongside each other during their careers and at times, control the same civil air traffic. The remuneration and benefits can be vastly different. This is not to say the reason for a transfer is about remuneration, but more about the recognition for the work that military controllers provide during their service.

2.4. Civilian ATCOs start their training with an initial course which includes a basic course and then rating training. On successful completion of this course, they are issued a student licence. This initial course can take anything from 6-9 months [5] depending on which rating they acquire. This process is to prepare the controller for live training at an ATC unit. With some recognition of the military qualifications and skills, this initial training is where time and cost savings could be made.

European training diagram – ATCO common Core Content

2.5. ATCO Licensing Regulation

2.6. ICAO Regulation

2.7. ICAO does not issue ATCO licences. Licences issued by ICAO contracting states on the basis of Standards and Recommended Practices (SARPs) of Annex 1 – Personnel Licencing are habitually called ICAO licences. This has led many to believe that there is a specific ICAO or international licence. There is not one single international licence issued by ICAO or any other organisation. States issue their own licences based on national regulations in conformity with Annex 1. [6]

2.8. As has been stated in last year’s paper (Licensing of ATCOs WP No. 159):

Most States have a licensing system for ATCOs. However, although the Standards and Recommended Practices (SARPs) for the licensing of ATCOs are contained within Annex 1, an ATCO licence is not mandatory. Unlicensed State employees may operate as air traffic controllers on condition they meet the same requirements.

2.9. A licence is not required by state employees who operate as air traffic controllers on the condition they meet the same requirements.

2.10. For states who will issue licences in accordance with ICAO, Annex 1 requires applicants to meet specified requirements in respect of:-

- Age,

- Knowledge,

- Experience,

- Skill, and

- Medical fitness.

2.11. However, each Civil Aviation Authority (CAA) may determine the manner by which knowledge and skill required for licences or ratings are to be demonstrated. The CAA may accept certain military qualifications and experience as being equivalent to some or all of the knowledge and skill requirements that must be demonstrated by civilian applicants and may issue a licence or rating on that basis. [7]

2.12. Most commonly in aviation, the recognition policy applies to pilots but it may also apply to other flight crew or air traffic controllers. If military air traffic controllers are not fully familiar with civil operational procedures and operate within accordance with military law and provisions, they should demonstrate the standard and knowledge required by Annex 1 as well as complete no less than three months of satisfactory service engaged in actual control of civil air traffic, under the supervision of an appropriately rated air traffic controller, before being issued with a licence. [8]

2.13. All ICAO states have their own methods of training. They set their own objectives, performance criteria and standards so it makes it difficult to recognise the training received elsewhere, even though ICAO allows for it. If, for example, all states and military organisations would use the ICAO Competency Framework for ATCOs, as contained in the PANS-TRG Part IV Chapter 2 Appendix 2, the training could be standardised.

2.14. ICAO has recently invited IFATCA to take part in a Personnel Training and Licensing Exploratory Meeting (PTL-EM) where the objective was to decide how to conduct the much-needed overhaul of Annex 1 on Personnel Licensing, especially for ATCOs. IFATCA wrote a paper with some of our concerns and requests with regards to personnel licensing, training and assessment which was endorsed by Eurocontrol and many other states and international organisations. It is very likely that the Personnel Licensing Panel (PLP) will be activated once more and will be in charge of the oversight of this activity. The ICAO Air Navigation Commission (ANC) will look at this possibility during its next session, approximately winter 2020.

2.15. EASA Regulation

2.16. The regulation in Europe for ATCO licensing and certification expands on Annex 1 and is covered in Commission Regulation (EU) 2015/340. From now on, referred to as regulation 340. This regulation requires each member state within the EU to train and maintain their ATCOs to the same standard. [9] EASA endorsed licences also meet ICAO standards.

2.17. In Europe, the structure for a harmonised European ATCO licence was developed to enable the licence qualification to more closely match the ATC services being provided and to permit the recognition of additional ATC skills associated with the evolution of ATC systems and their related controlling procedures. [10]

2.18. This development of regulation within Europe allows for the freedom of movement of people. An ATCO licence that is issued in a member state in Europe will allow the holder to use their licence in another member state (subject to an adapted Unit Endorsement Course (UEC) and licence exchange). [11] The European licence has proved an effective way of recognising and certifying competence of air traffic controllers within Europe.

2.19. Common rules for issuing and maintaining licences are essential to maintain Member States’ confidence in each other’s systems. As such, and to adhere to the common licencing rules, the Civil Aviation Authorities within Europe, will not accept a licence issued outside of the European area or issued by a military organisation for exchange.

2.20. This is because the CAA has no knowledge of the ATC training syllabi of courses undertaken by organisations outside the European area and military organisations and how these compare with regulation 340 training content. As a result, the CAA is unable to recognise the ATC training undertaken in non-EU member states or by military organisations. [12]

2.21. Because there is no formal guidance in regulation 340 for recognition of a military licence, the Initial Training Organisation (ITO) would have to compile an initial training plan which would then have to be approved by the CAA. This task would require the ITO to analyse the training the military controller has undertaken and provide evidence to the CAA that the plan will meet all the objectives laid out in the specification of ATCO training. It is the same process that would have to be followed if a controller wished to convert their ICAO endorsed licence to an EASA one.

2.22. For military pilots in Europe, there is EU Regulation 1178/2011. This regulation covers the administrative procedures for aircrew and interestingly, allows credit towards an EASA pilots licence for pilots’ licences obtained during military service. Where ICAO has policy, which can be applied to military personnel in most aspects of aviation, from engineer to ATCO, EASA regulation will only consider pilots, for credit towards licence conversions. [13]

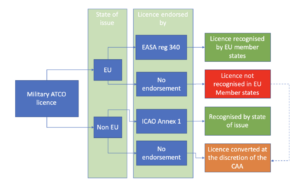

2.23. The result is that, as seen by the above flow chart, ICAO will allow a military controller to effectively gain a civil licence if the applicant can satisfy the CAA that they have met or exceeded the requirements for issue. This option is not available with EASA and as such a military controller in Europe would be required to complete a training course to obtain a civil ATCO licence. There have been occasions where military controllers have left Europe altogether to gain employment in ICAO states where their experience can be credited towards the gaining of an ICAO endorsed licence.

2.24. This is not to say that in Europe, an initial training course could not be reduced in length. There is no required minimum length but the objectives for obtaining a licence have to be approved by the CAA before the training commences. Through prior assessment and examination, the knowledge and skill of the applicant could be checked and the training adapted to suit the applicant’s needs.

2.25. There is one conversion course being offered in Europe at FTE Jerez [14], Spain. This is the first of its kind to be delivered in Europe. To gain approval for this course was a real challenge for the organisation and the syllabus spans 465 pages and took more than 6 months to develop.

2.26. This course is only for Spanish military licence holders who wish to gain an EASA endorsed tower rating. On request, the training organisation will have to analyse the original training the applicant undertook during their military service and then crosscheck this with the EASA syllabi. Any gaps identified in the training programme can then be covered before a licence is issued. This reduces the course length by an estimated 45%.

2.27. The complex nature of the EASA regulation towards training and the lack of information on how to recognise military experience results in very few states in Europe offering any kind of recognition of military experience.

2.28. Survey of Member Associations

2.29. From the countries surveyed within Europe, Italy is the only country that licences their military controllers to comply with regulation 340. The United Kingdom, Netherlands, Latvia and Romania do not licence their military air traffic controllers to comply with regulation 340 and this results in the military controller having to commence their training at an ITO to obtain an EASA endorsed licence. Romania did try to align their licences a few years ago but this was stopped for unknown reasons. Latvia train their military controllers in the USA and sometime in the future the training will comply with regulation 340.

2.30. As previously mentioned in the paper, Spain has converted military tower licences with the course offered by FTE Jerez. This process cut the initial training (Basic and rating course) time by 45%.

2.31. New Zealand can recognise military experience towards the issuance of a student licence. New Zealand is the only one of a few countries that do and as such, military controllers will often leave Europe to become civilian ATCOs in New Zealand. If the applicant has exercised the privileges of their licence within 6 months of starting the course, the training organisation can test the previous knowledge of the applicant and offer a reduction in the initial training phase. New Zealand licences are endorsed by ICAO.

2.32. In Kenya, both the military and civil air traffic controllers go through the same training and even share classroom studies. The military air traffic controllers also then go on to do their On-the-Job-Training (OJT) and rating boards in civilian airspace before going back to military control.

2.33. In Canada, military ATCOs looking to transfer to civilian ATC are required to complete the full training an ab-initio would undertake. This is because Nav Canada does not know what the syllabi were on their training courses or what kind of air traffic control they were providing.

2.34. The USA, when hiring directly from the military, require the military ATCO to have at least 52 weeks of continuous air traffic control experience. Each controller is assessed individually and may then be able to bypass the FAA training academy.

2.35. In Australia, the ANSP will only accept applications from military controllers who have worked at ‘joint-user aerodromes’. Military controllers at these locations are required to apply civil ATC rules and are therefore familiar with them. They also hold licences with ICAO endorsement. Even though they hold an ICAO endorsed licence, the applicant is still required to undergo an initial training programme. As there are few joint-user aerodromes, the training team have been able to create templates for these trainees. Once this training is completed, they are trained to the same standard as other trainees and then undergo unit training.

2.36. South Africa train their military controllers to ICAO standard. Whilst movement from the military to civilian has slowed in recent times, when military controllers did transfer to civilian ATC, they were given a one-week course requiring them to complete all theory exams and the final practical test. If this was passed then they did not have to complete the course.

2.37. What are the barriers?

2.38. Unlike ICAO, there is no guidance or policy in the EASA regulations to allow for a CAA to convert or transfer a licence of an applicant whose licence does not conform to regulation 340 standards. It is possible with an alternative means of compliance but it is difficult and time-consuming. As described previously, outside of Europe, the CAA may allow credit for previous experience or qualifications which are held by the military ATCO but this happens infrequently and with many caveats.

2.39. For an ICAO licence conversion, the CA must be aware of the training received and of the operations or activities conducted. This can be a difficult, time consuming task with inherent risks and demands on the CAA. If this is accomplished, however, the licence can be converted relatively quickly. The process in Australia is a good example where the ANSP has created templates after working with the joint-user aerodromes to ensure the training given is efficient and results in a trainee of the same standard expected from the training course.

2.40. If the candidate is not fully familiar with civil operational procedures, they must demonstrate they have the standard of knowledge required to comply with Annex 1. This would require the CAA to assess the previous competence of the military ATCO and then potentially having to train them for some time. This situation might not allow for a worthwhile reduction in training time in comparison to an ab-initio.

2.41. Even though there is currently a controller shortage, the number of ab-initios entering the training system could be enough for or more than the training system can manage. Coupled this with the number of military ATCOs wishing to transfer being relatively low, the ANSP might not want to cater for the small number of military controllers looking to convert their licence. Even though in Europe it can be difficult to produce a conversion course, it has been done. If the demand increases then there is likely to be more courses created of this kind.

2.42. The conversion course being offered by FTE in Spain is one that could be considered by the ANSPs when they are approached by military controllers who wish to enter civil ATC. With courses taking approximately 6-9 months, the time saved could be advantageous for both the individual and the ANSP.

2.43. A military organisation might want to limit the movement of military ATCOs to retain an ATC workforce and maintain military ATCO retention. The remuneration and benefits are usually better in civilian ATC and if the licence conversion was an easy process then the number of military ATCOs leaving might be detrimental to military organisations. States can sometimes overcome this with non-transparent ‘gentlemen agreements’ between ministerial departments. Military organisations have to consider methods of personnel retention with regard to allowing service members, who have served a minimum number of years, to be considered for transfer into their civil ANSPs.

2.44. One of the difficulties of transferring from military to civil is not just the learning of new topics for civil air traffic but the “unlearning” of methods and techniques that have been used for many years previously. Some controllers who have completed the conversion courses often find they can revert to the phraseology associated with their military experience, for example.

2.45. EASA is currently holding consultations to update ATCO rules in Europe. Of the many topics, one which will be discussed is the “recognition of third country and military licences”. These discussions are taking place after the deadline for this paper and is something that PLC should consider revisiting in the future.

2.46. ICAO is also working on ATCO licence transferability however this is unlikely to cover military ATC licences.

2.47. This paper concentrates on the recognition of military licences however the wider topic is licence transferability for all controllers globally. Whilst out of scope for this paper, it is a topic that could be considered for papers in the future.

2.48. Case Studies

2.49. For this paper, two people who have undergone a transfer from the Royal Air Force (RAF) to civilian ATC roles were interviewed.

2.50. One controller applied to NATS through the same process that an ab-initio would be required to do. They then carried out their training with no dispensation for previous ATC experience given, and all classes had to be attended and exams passed. On successful completion of the initial training course, they were issued a student ATC licence endorsed by EASA. The controller has since gone on to live training.

2.51. Another UK RAF controller left the military and started a conversion course in New Zealand. They were required to pass all the ICAO exams in the following subjects:

- Air Law

- Air Operations

- Meteorology

- Navigation

- Human Factors

- General Aviation Knowledge.

2.52. Then they had to pass a simulator exam and an aerodrome exam before moving into live training. Their previous experience allowed for the simulator training to be skipped to exercise 12 which would have taken approximately 2 to 4 months to get to.

2.53. All of these elements allowed the course to be reduced to approximately 5 weeks from a usual course length of 8 months.

2.54. This controller added that they have never worked so hard in their life, and they have tended to revert to the standard phraseology that they used while in their military service when they are really busy on the radio.

2.55. IFATCA Technical and Professional Manual (TPM)

2.56. Currently, there is no policy in the TPM for ATCO licence transferability nor policy for military licence recognition.

Conclusions

3.1. Military air traffic controllers are leaving the profession with years of experience. In an ideal world, military air traffic controllers will have been trained to ICAO or EASA standards but as this is not always the case, there will always be requests for recognition of experience.

3.2. Only a small sample of Member Associations have been surveyed and there are almost certainly more ways licence conversions are managed around the world that didn’t make it into this paper. It has at times been difficult to get detailed examples of a states processes due to the sensitive and complex nature of the topic.

3.3. There are however some good examples of military licence recognition. New Zealand takes a pragmatic approach and allows for a reduced basic and rating course for controllers with previous experience and Spain provides a conversion course for military controllers looking to transfer to civilian ATC.

3.4. There are examples where this is not the case. Mainly in Europe where there is no recognition resulting in military controllers having to complete a full training course with increased costs for either the ANSP or the individual, but also in Canada where a military ATCO would have to complete a full initial training course.

3.5. Even with processes in place, there will still be an element of re-training that comes with changing jobs/roles. The process will take time and will require significant commitment.

3.6. The onus on licence recognition will always be with the Civil Aviation Authorities. There should be processes in place to allow for credit towards the gaining of a civilian licence to enable a reduction in training times and to make the conversion training more cost-effective for either the individual or the ANSPs.

3.7. This paper has focused on the military licence however the issue of global licence recognition for all air traffic controllers is a much larger topic and one which is currently being discussed within EASA and within ICAO in the future.

Recommendations

4.1. It is recommended that the following be accepted as policy and inserted into the TPM.

TRNG 10.4.X Accreditation of military air traffic control experience

Civil Aviation Authorities should recognise the competencies and experience of military controllers and apply appropriate credit towards civilian ATC training where the applicant provides proof of relevant experience, qualifications and knowledge.

To facilitate this process, all ATCOs, whether civilian or military, shall be issued a licence which complies, to the extent possible, with ICAO and/or EASA requirements.

References

[1] https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-scotland-business-45057103 [2] https://airtrafficmanagement.keypublishing.com/2018/06/14/atc-staff-shortages-strikes-disrupting-millions-of-passengers-this-summer/ [3] A4E – Airlines for Europe. [4] EU 2015/340 Article 3.1. [5] Times based on surveyed European and non-European associations. [6] https://www.icao.int/safety/airnavigation/Pages/peltrgFAQ.aspxICAO Convention on International Civil Aviation – Annex 1.

ICAO Doc 9379 – Manual of Procedures for Establishment and Management of a State’s Personnel Licensing System.

UK CAA CAP 1251 – Air Traffic Controllers licensing.

EASA Commission regulation (EU) 2015/340.

EUROCONTROL Specifications for the ATCO Common Core Content Initial Training.

EASA Commission regulation (EU) 1178/2011.

ICAO Doc 10056 – Manual of ATC Competency Based Training and Assessment.